We’re three days into our stay in the north-western state of Rajasthan, and are heading by bus to Bikaner for our last night before going to Agra tomorrow night. Instead of hotels or hostels here, we’ve been in homestays, living and dining with three very different families who call this desert state their home. So far, Christine and I agree that this might be our favorite part of India yet.

This leg of the trip didn’t start off too well, though. We left the Palm Grove “homestay” (they call it a homestay, but it was really just a hotel, although Christine commented that it seemed like the owner was sleeping in his own office so perhaps it was a homestay in that case) at 5 in the morning to make it to the airport for our flight at 8am. However, it was delayed for 45 minutes, which caused us to miss our connecting flight to Rajasthan in Mumbai and be waylaid at the airport. MakeMyTrip.com, the Indian website that Christine had booked through, had only given us 1.5 hours between flights – a risky bet in any country, and much worse in the 3rd world.

We had to quickly decide what to do as the flight attendants at the ticket counter politely but firmly refused us to go any further (even though our plane wasn’t leaving for another 15 minutes) – “sir, you cannot check in after 45 minutes before your flight” – even when we argued that it wasn’t our fault because our previous leg had been late. But MakeMyTrip had booked us on two different airlines so we couldn’t go to either of them for assistance. Long story short, fellow foreign travellers – scrutinize that website’s offerings very carefully before booking anything with them. In the end, we picked a first-class ticket on Air India to get to Jodhpur city, our Rajasthan state destination, on the same day – every other economy class ticket was on the next day, and we had a homestay waiting for us.

That was kind of fun (although for $400 a person compared with $50 a person for our original tickets, it had better be fun) – they kept bringing us newspapers, magazines, juice, and tea, and hot washclothes. And we were the only people in first class…Christine and I both joked that this is how these 2 hour flights get anyone into first class, just poor saps like us who had no other choice but to fly first class or have to ruin their travel itinerary. At least we had plenty of leg room, and we were the first ones off the plane too of course. I’ve actually never flown anything but economy before; Christine said she’d never paid for anything higher, but had been bumped up once.

It was fun, but I hope that the flight insurance Christine got will cover at least part of the $800 in tickets we had to buy...

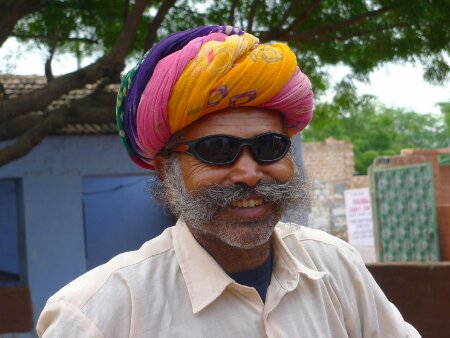

Our first homestay host, Chhotaram Prajapat, was waiting for us outside the dusty Jodhpur airport. Walking outside into the dry, bright sunlight was like coming back to Jordan, except cows were everywhere. Strolling along the road, along the sidewalk, crossing the street, and just standing completely fearlessly in the center of the street…they were a constant sight. Our bearded new friend Chhotaram was a quiet, friendly fellow who hardly ever honked at the cows and bulls all around him as we headed to his village in Salawas, just south of Jodhpur – I liked him already! We couldn’t believe it, but we found out that he was only 25 years old and already had three kids. The desert sun definitely can age a face, I thought he was early to mid thirties. His mother and father Darhiya and Pukrohgi actually own the lands of the house (it’s been in their family for over three hundred years, as their ancestor came here from Jodhpur to be an artist and the town kind of sprung up around him).

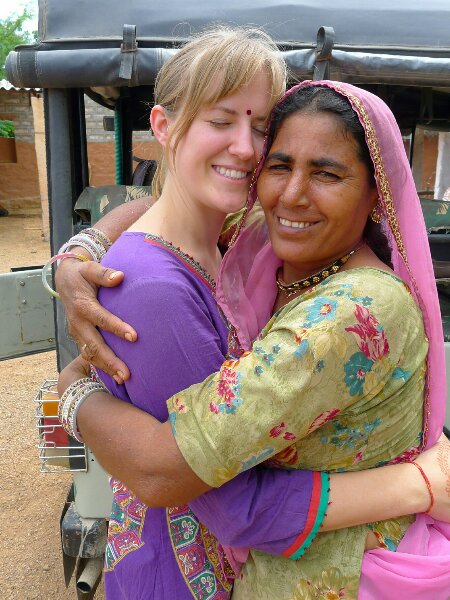

Darhiya took an instant liking to Christine and I as she tied bright red and gold bracelets around our right wrists and ritualistically intoned something in the local Rajasthani language, Marwati, to welcome us to their household (I’m still wearing mine now!). Especially Christine, who she called her big sister even though she had to be 50 years old or so – but she just meant taller, of course! Pukrohgi wore a fine white turban and sported an equally fine salt and pepper mustache which he wore so long that he often wrapped the ends of it around his ears like spectacles. Chhotaram, his wife, and their three children were the formal inheritors of the household as the eldest, but Chhotaram’s younger three brothers still lived with the household too – only his two sisters had been married off already and lived elsewhere. But it was a big family, and they were eager to chat with us and find out more about America, as much as we were eager to chat with them.

Chhotaram took us out to a large bluff near his home, about a 10 minute walk. In the extremely flat lands of Salawas, the huge rocky steps were an odd site as they seemed to rise out of nowhere as we turned a corner. A gaggle of local children now followed us up the cliff, singing Hindi pop songs, tossing stones around to see who could go the farthest, and of course trying their best to find out more about us using their limited English. On the bluffs, one was quite happy to climb up a rock wall behind us and show off how high he could go, as the others looked at us, nodded sagely and said “He crazy monkey.” Chhotaram sat on the edge of a rock and watched the sunset over the green fields of the desert with a small smile, saying little but answering the kids’ questions when they asked him. We joined him and watched the sun set over the scrubby trees.

Trying out some yogurt curry - you can see baby Vasudev here, and daughter Kusboo's English alphabet school work on the chalkboard

Back at his homestead later that evening, we had a fine yogurt curry dinner, with potatoes fried in ghee fat, and lots of tasty chapatti bread. Christine says that one thing Indians are masters of cooking is many types of bread, but I think chapatti is my favorite. Christine cooed over Chhotaram’s youngest child, a two week old boy named Vasudev who had little black eyeshadow marks at the corners of his eyes – we learned that in Hindu culture, black lines or smudges are put on things you care about, in order to ward off the evil eye or bad luck. A few days later, our other homestay host Gemar would explain it as making sure the mind didn’t have 100% of its energy or chakra (or something?) focused on the beauty or cuteness of what you were looking at – as long as a little bit was distracted by ugly black tassles hanging off a car’s side mirrors, or smudges of black ash under a child’s eyes, you wouldn’t be able to focus evil energy on whatever you were looking at. I suppose it’s similar to the Muslim practice of writing “Ma sha’ Allah” (This is by God’s will) on the on their cars and trucks and saying it immediately after complimenting a parent on their children. Even in America we have old vestiges of that, like when we say “Knock on wood!” after saying something hopeful. But here of and in the Arab world of course, it’s taken far more seriously. You’re supposed to spit over your shoulder twice if you compliment someone, even.

Mumta's henna work - Christine said that she liked it a lot more than the stuff she'd tried to do before I arrived in Kerala

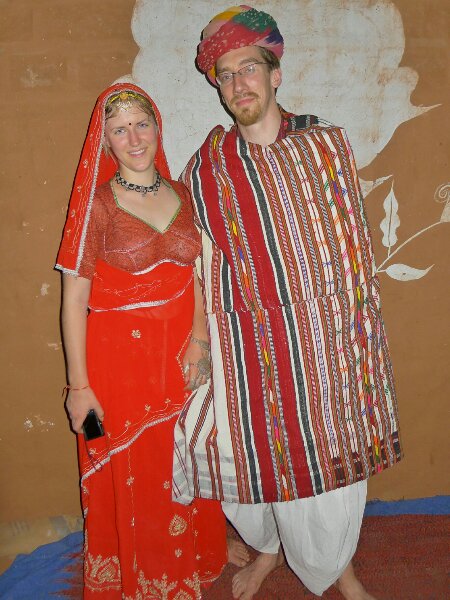

After dinner, Darhyia dressed up Christine in a red silk wedding dress with bangles hanging off of her, and Pukrohgi put a camel hair robe on me, and made a turban for me out of a thin, 9-meter long length of rainbow colored cloth, while Chhotaram’s 22 year old wife Mumta covered Christine’s hands in henna art – the acrid-but-pleasant lemony smelling black goo was smeared out of a paper tube. Finally, Christine and I had a couple of beers up on the roof of the homestead, looking up at the clear night sky – the Prajapat family as Hindu didn’t drink, but they sold us a couple of beers that they had brought from Jodhpur for their guests. At our request, they dragged out some bedframes into the yard for us to sleep on – while we loved the branch-thatched roofs of the huts that Chhotaram had made when starting his homestay business 3 years ago, we enjoyed sleeping out in the cool night air even more, at least until the flies started landing on us as the sun rose the following morning, when we escaped back into the hut, around 5:00. Around that time, I glimpsed Darhyia getting up to milk the cows to make the milk to add to our chai in a couple hours!

Chhotaram had to head back into Jodhpur to get some more tourists, but Pukrohgi and the 2nd eldest son Samburam had a second jeep and took us on a “village tour” around the fields and huts of their rug-making cooperative, and beyond. We were a little hesitant when our first stop was too a villager’s household named Vishnoy, who Pukrohgi told us in very halting English was part of a famous clan because they believed a certain kind of tree, the kazjri, were holy – and when developers in the city tried to knock them down a hundred years ago, many chained themselves to the trees and were subsequently killed. Mister Vishnoy intoned some words over a shrine to Shiva, then powdered something in a stone tray, mixed it with water, and filtered it through what looked like a sock. He then poured a bit of it into our right hands and gestured for us to drink it. “Opium party!” Pukrohgi said happily, as the Vishnoy’s son handed us some chunks of black crystal. “Opium with sugar!” he said again behind us. “Eat, eat!” Exchanging glances, we shrugged and popped the little pellets into our mouths….when in Rome, after all. I asked Samburam, who despite being much more silent than his gregarious father, spoke a bit better English, whether opium was legal in India. No, we were told, unless you have a medical need for it, and that’s why the old man has the legal right to use it. I didn’t ask whether that included sharing it with tourists on a village tour.

The vishnoy and his filter device. They sure like putting turbans on their guests! Note the goiter (or something) on the side of his face - perhaps the reason for his medicinal usage?

As we drove on narrow roads past clearly hand-planted fields of millet, lentils, and gum (we didn’t know what they meant when they told us the last one), we could hear a cackling haa-haa-haaaaa! call coming from in some trees, and out deeper into the fields. Finally, Pukrohgi pointed out what it was – there were peacocks and peahens running wild all over the place, and a few of the males were showing off their plumage. “India national bird!” Pukrohgi announced. “Village tour good!” As we drove, we often passed men and women walking on the road, or working out on the field. Later in the day, Christine asked Chhotaram why some people looked at us, and Pukrohgi so sternly. He seemed a bit embarrassed, but Christine hit on the obvious pretty quickly – “What do people who aren’t part of your cooperative, or your village tour think about your 60 USD a night new business of inviting foreigners into your home?” He shyly admitted that there was some jealousy, people wanting to be part of it and gain some of the money from it. I applauded his business sense though, and told him that it was his good business sense that allowed him to get the idea of homestays from a British friend that he sold rugs to, that had stayed at his home with his family some years ago. Chhotaram then asked his cooperative for financial assistance to build the 7 mud, dung, and stick huts (but with running water, electricity and fans) behind his home, and then share the profits from visitors with his community.

On the tour, though, people whose homes we stopped at (who were presumably getting a cut of the village tour money) were extremely cheerful and pleasant to us, and happy to show us around. We met an 83 year old woman, tiny and stooped, in a tiny mud hut where she was making chapattis over a cow dung fire. Christine and I had tried making chapatti last night for dinner with Mumta, and although she had succeeded on her third attempt (a woman’s touch, perhaps) mine were so bad that they had to be rolled back into a ball and redone as Darhiya, Mumta, and Christine laughed. Watching the women make them was mesmerizing though – they could do it in a seconds, making little balls of dough in their palms, then rapidly spinning them in their fingertips, pressing out the edges millimeter by millimeter. When I tried doing that, my fingers went right through. This old woman seemed to be even faster if that were possible – she probably had 77 years of experience at it.

We saw antelopes with fluted horns galloping through the fields, and wild dogs everywhere. We stopped at a local potter, a Muslim family who were relaxing in the shade (Eid al fitur was the next day, so they were still fasting during the sunlight hours) but the potter, a 30 year old man with very strong arms, spun up his wheel with a long white stick. I couldn’t believe that with neither electric motor nor even a foot-pedal with a belt, he was able to make perfect pots, plates, and cups so easily. Christine and I each succeeded in making a plate, probably because of too much pressure. I could imagine his thoughts – “Pukrohgi’s bringing more tourists. Geez, I have so many plates already.” After the potter, we went to a women’s cooperative textile recycling shop named Dil, where we were given a smooth sales pitch and beautiful presentation of at least 50-60 different textile pieces. Our host Vikram told us that over fifteen thousand women from around the villages south of Jodhpur were employed making these textiles – he drove around every month providing fabric and designs to them, then coming by the next month and picking them up, giving out new material, and providing payment. There was a room with women cutting up old dresses and saris to be made into recycled wall hangings – they were so pretty that I bought one made of red and black dresses to hang on the wall behind wherever I decide to put my Rajasthani dresser.

Back at the homestay, Chhotaram chatted with us over lunch and then, before driving us back to Jodhpur for our next homestay, showed us how his family and their cooperative had been making their rugs, called Durry, for three hundred years. He and his mother worked over a long loom that had an arm on it that could make the long cotton threads flip between top and bottom, and then they threaded camel hair, coconut fiber, and wool through the strings, beating them into tight placement with a wooden fork.

Chhotaram dropped us off personally at our next homestay, a large house in the middle of Jodhpur city called Mohan Niwas. He helped carry in our bags and gazed a bit awkwardly around the opulent front yard before we said our farewells and he and his jeep disappeared into the busy Jodhpur traffic. Our new hosts were Chottu Singh, her husband Mahinder, and his father Maden. We were greeted in flawless, British-tinged English and showed to our rooms, as servants silently carried our bags behind us. This was definitely going to be a different experience then Chhotaram’s farm!

We learned that Maden was the fourth cousin of the Maharaja – the king – of Jodhpur and they and their other extended family members owned all the homes on this block in the city. Mahinder took me up on the roof as Christine napped a bit and pointed out other homes around them, rattling off connections – great-uncle’s home, third cousin over there, etc. I suppose when you’re part of the royal family remembering lineages just comes perfectly natural to you! We wanted to make the most of our daylight hours, though, by seeing the famous Jodhpur fort that presided over the city on a cliff. Chottu called one of the rickshaw drivers that they kept on retainer for their guests, who gave us a very good rate – 300 rupees for the rest of the day. Before we left, we washed some of the dust off our faces in a bathroom that was the size of my bedroom back at home!

We leisurely explored the fort, which was packed with Indians excitedly pointing their cameraphones at something happening up on the ramparts – it turned out that some sort of movie or music video was being shot, although all of the producers and tech people were too busy shouting “move move move!” at Western tourists to tell us what was going on. Fine by me – I came to see a fort anyway, not a film shoot. Christine and I were both impressed at the well organized displays of palanquins, howah elephant chairs, daggers, and minutely detailed “miniature paintings” that were all the rage 200 years ago by the old Singh maharajas. We saw grand throne rooms and much smaller ones, but they all had exquisite panels of mirrors, or dark wood, or ceramic tile and jewels, or sometimes a mix of everything – especially since the British style had encroached in the last hundred years as well. The current maharaja Singh and his family no longer lived here, the audio guide told us (and our hosts confirmed later) – they stayed in a grand palace named Umaid Bhavan on the other side of the city, half of which had been turned into an elite hotel and restaurant with minimum plate costs of 3000 rupees – or about $50. In a country were you can get a full meal for $1, they were definitely catering to a different class of people. I guess if you’re not officially royalty anymore and not receiving taxes from the common people, you have to make your money somehow!

Over dinner with the family, we learned that the family (and most of Jodhpur, we were told) still referred to the old Maharaja by the title “His Highness.” I asked what the Indian government, with its president and prime minister, thought of that. Maden chuckled and told us that on letters from the government, he was just “Mr. Singh” – a private citizen, in their eyes. Their house was filled with pictures of their family members, either solo portraits or many people together, including Maden with the maharaja and the crown prince, a dashing looking young man in his 30s. We were joined at dinner by Maden’s other son Reggie, who chatted with Christine and I about the Midwest – it turned out he had gone to Kalamazoo university in Michigan and enjoyed hunting and sport in the Upper Peninsula. He owned a safari and hunting lodge in the north of Rajasthan, and talk turned to managing websites – it seemed that he was being ripped off by his web designer who was still charging him the equivalent of $100 a year to do nothing more but change the prices of his lodge. I told him about WordPress, of course! I also helped Chottu and Mahinder’s daughter Kanika set up a defunct router in their accountant’s office – the whole family was under the impression that they didn’t have wireless available in the house – Kanika, a law student around our age, freely admitted that technology wasn’t her strong suit – but from their business computer I was able to re-enable wireless on it and set up a password for them, much to the family’s delight. “Now I can have grandpa add “wireless available” to our website!” Kanika said happily, “and I can do my homework from my laptop!” What can I say, I miss work already! It never hurts to have good connections in another country in case one wants to move overseas again, and what better connections then the royal family?

Rishi also took us to his (pictured) cousin's tea shop. Warning: this man will smoothly sell you tea you don't need

Our third and final homestay was to pick us up at 3pm the next day, so we hired out the rickshaw driver from yesterday, Rishi, to see Umaid Bhavan from the outside (it was imposing and beautiful, and extremely well guarded by security with machine guns) and then to see the private school that Chottu worked as an administrator of. She greeted us warmly at the gate and showed us the lunchroom, which was what she primarily oversaw, the large hall where they were preparing for an inter-school quiz competition (hence her work on a weekend), the playground for the younger kids (which had a beautiful mural on the wall behind it), and to my embarrassment, even the dormitories for the girls. Christine, a teacher in her own right, marveled at the way that as Chottu passed by groups of students, young and high school age, they all popped to their feet and chorused “Good afternoon ma’am” in polite English. The dorm headmistress bowed respectfully to Chottu and the two of them seemed even likely to show us the girl’s bathroom until I said that I was content to leave the rest of the girls’ home to their own privacy! The girls (we seemed to be a dorm for the 10-13 year olds, although I’m terrible with telling Indian ages, as I was with Arabs) gazed at Christine and I with wide eyed smiles, with beds only 6-12 inches apart. It reminded me of summer camp, and I asked Chottu if there were ever fights because there was no privacy. She laughed and said “oh no, the girls love to talk long into the night, they pull their beds closer to each other to whisper after lights out.” There was even a shooting ground being built in the corner of the sport field – the British scholastic organization the school was part of apparently had international sporting games that included rifles, and both Christine and I commented that it would be strange in the USA to see a shooting field so close (only 50 meters) from a dormitory. All and all though, it was a beautiful campus – and like Jordan before, we learned that most Indians, poor and rich, would send their children to these private schools, which are actually known as public schools to Indians. The government of India has their own free school system of course (what we Americans would call “public schools”) but in Indian parlance are called “central” schools instead. All of the Indians we spoke to spoke to seemed happy that they existed, but none of them wanted to send their kids to them. Hmm.

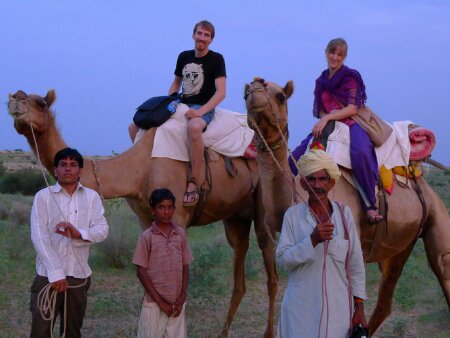

Maden, Mahinder, Chottu, and Kanika saw us off as their servants loaded our bags into the car that our last homestay, Gemar Singh (of no relation) had sent to pick us up. We were headed to the village of Osian, a couple hours to the northwest of Jodhpur, where we were greeted by Gemar himself, a trim man with a huge bristling black mustache and silvery-black hair who spoke very good English. He greeted us warmly, then directed us to the first part of our stay – a camel ride out into the desert outside of Osian, to his village of Hacra a few kilometers away. He drove our bags off as our camel drivers, a young man named Killesh and a hugely-mustacchioed elder named Ganeshram, helped us up onto our camels. I won’t call myself a camel-natural, but after riding them a few times in the deserts of Jordan, I feel quite comfortable on them, and the young female camel I was riding, Chidmi, was quite even tempered and content to be led by Killesh, as was the elderly camel named Pappu that Christine had. Osian was a small city, and it didn’t take long for the sound of of traffic and dogs to fade away behind us and be replaced by the winds rustling through the scrubby trees and bushes, birds, and farmers tending their goats. Christine and I had seen the negative reviews on Tripadvisor of Gemar’s homestay, mostly from people who complained that the desert “wasn’t desert-y enough” – foreigners who had expected the place to look like the Sahara or something. However, this was India, not the middle east, and it was also monsoon season, so although we were walking over sand, there was small grasses everywhere, and lots of bushes and trees.

Children glimpsed us from afar, and ran from thatched huts, dancing around the camels shouting “tata! tata! tata!” Gemar told us later that Tata was a common child’s word for saying hello and goodbye, probably because so many of the cars and trucks had the word printed on them that it became associated with coming and going. (you may recall that Mr. Tata was a magnate in Mumbai that created the history museum I enjoyed so much). The little girls clustered below us and hopefully said “Choc-oh-let candy?” Christine and I didn’t have any, we said apologetically, but I did have a sucker left over from a hotel in my pocket, which I tossed down – when they saw it in my hand they practically punched each other to grab it, and Killesh said with dismay “no no no!” and his body language implied that my bit of generosity was going to make his future tourist trips even more a hassle with kids swarming around his camels even more than they were already. The girls that were unlucky in the candy throw trailed after with pouts, murmuring “candy? candy? candy…” until finally giving up as we left their huts behind in the dunes.

Gemar met us after about an hour and a half on the saddle – “a good stopping point” Christine said as she stiffly got up off of Bappu. Not too long and not too short – I still remember how sore my parents and I were after our 3 hour ride in Wadi Rum in Jordan back a few years ago! Gemar’s jeep bumped out of the desert ruts and back onto a paved road within a few minutes as twilight fell around us – turns out we weren’t that deep into the desert after all! We found out that he was actually a university graduate, studying history and languages – not necessarily the most common thing to find out here in the farmlands and deserts. His farm was very different from Chhotaram’s – a single small house on a hill, with a few mud and thatch huts 50 meters away that were not dissimilar to the ones we’d already stayed in – sans electricity and running water in this case though. However, if Chhotaram’s homestay had been quiet, then this farm was almost silent – a dog named Suri greeted us, a couple small cows, and a patch of land 50×70 meters – and Gemar’s wife Meera and son Rawol. He said he had a daughter too, but she was staying with Meera’s parents a village or two away because there was a better girls’ school there then what was near Hacra. “I talk to her every day on the phone though,” he said with a sad chuckle.

During dinner (which was a delicious buttermilk curry, even better than the yogurt curry at Chhotaram’s in both our opinion) and long into the night until my head was nodding into my chest, Gemar talked with us about politics and religion – Christine was particularly talkative on the latter. We learned about the aforementioned black marks to ward the evil eye, about the difficulty of securing a government job (which had been his original intention in university, after which he started his homestay). Why? We wanted to ask – why leave your parents behind and take your wife out into the desert? “I was curious about Western people,” he replied. “I would see them on my bus ride to school in Jodhpur, and wonder why they were here – why come to India, and Rajasthan, and Jodhpur? What could we offer them?” So he bought a little patch of land from his uncle, who had lived out here before, and started his homestay – which, in my personal opinion, was a bit pricey at $152 for the two of us for one night. Even with the camel ride thrown in, and transport from Jodhpur to Osian by car, Chhotaram and his family had only charged $60.

It was still a lot of fun though, as we dragged mattresses onto woven mattresses suspended off the ground on metal frames for the night. We had a flashlight to find the bathroom in the night, which had western toilets but no running water (“yet” said Gemar ruefully, “but maybe next year”) and a few of the everpresent desert geckos scurried into the shadows. It was even fun when it started raining on us at 2am or so and quickly ran back across the yard with our blankets into the stuffy (but snug and dry) huts, which had mosquito netting around them.

The next morning, there wasn’t much to do besides eat a tasty breakfast of plain yogurt with tasty apples and bananas mixed into it, and have some sweet millet paste on chapatti. Christine and I walked the length of the farm, which didn’t take long, and petted the dog and tried to pet the ornery cat, who was unnamed because as Gemar said “Rawol names the animals, and the cat doesn’t like anyone so we just ignore him and let him catch his mice” Peacocks were calling everywhere, and we saw them perched photographically on the fence posts of the other farms a few hundred meters away farther down the hill. Despite being separated by a sizeable distance from his neighbors, Gemar seemed to be visited quite often – the children had the day off because it was Eid al-Fitur, and a neighbor boy came by to have Gemar help him with homework – I imagined that the university-educated neighbor got a lot of visits from kids for assistance! Christine played some Beethoven on her iPod for Rawol, who seemed to love it – he had a shy smile and he would always lower his eyes when we looked at him but he seemed entranced listening to the 9th Symphony, gazing off into the distance and moving his lips slightly. I have to remember to email Gemar the audio file when I get back to America – Gemar is cut off from outside all outside utilities except for Internet (he has a USB 3G dongle that he plugs into a small laptop) and they get water from trucks that come by when called. Electricity is provided from a single small solar panel that is mounted on the roof, and through that, Gemar is able to keep in contact with visitors like us with ease.

He drove Christine and I back to Osian to catch that bus to Bikaner that we’re now on, (and this blog entry at last draws to a close!) but we first stopped by a couple temples – a Jain temple that was quite famous and filled with intricate stone carvings (an English speaking man spoke with great pride that he was the stone carver for the temple, and his father and grandfather had been carving for Jain temples for a hundred years. I asked him if he was Jain, and he said “oh no! We are Hindu. We just love the shape and patterns of Jain architecture and wish to replicate it for all temples in India if they wish.” Old men and women were sitting in the hot sun, making mandelas out of rice – mandelas are meant to be mind focusing exercises, allowing a person to focus a single simple task of making intricate patterns with the rice, only to blow them away when finished – a reminder that all things on earth are impermanent and that ownership is impossible. The flies seemed extremely happy about this.

The Durga temple a few blocks away was packed full of devotees – apparently today was a holy day of some kind. As Christine and I expected, we were quite gawked at by patrons and beggars alike. Over a hundred steps led up to the temple itself, which was filled with smoke, incense smells, and carved black stone. A security guard spied us and allowed us to walk on a separate walkway to just enjoy the architecture of the temple, leaving the Indians to go up to the alter to make their offerings and prayers.

We lost Gemar when we got back down, and spent half an hour walking through the city hunting for him – me silently (and not so silently) regretting that we had no phone to contact him with, and we hadn’t seen where he parked the car when he dropped us off at the Jain temple. An old woman came up and shouted at us for money, chasing after us for a few dozen meters, and we fled back to the Jain temple, where we found that stonemason and got him to call Gemar for us…whew! Ladies and gentlemen, don’t lose your guide when in a tiny town in rural north India.

And here we are, being stared at by a couple dozen Indian farmers and their wives as we journey north toward Faloodi, the transfer point when we’ll switch to a bus bound for Bikaner. It will be nice to stay in a hotel again tonight and have time to ourselves again – but homestays are great. All three were very different, from the boisterous family atmosphere for Chhotaram, to the elegant beauty of the Singh mansion at Mohan Niwas, to the stark quiet beauty of Gemar’s tiny plot – I recommend them all, although if we had to pick, Christine and I agreed that Chhotaram’s was the most fun – Darhyia just doted on Christine, hugging her tightly before we left and calling her sister, and Christine loved her and the children – and I thought the men were a lot of fun to talk with, especially old Pukrohgi and his big grin.

I hoped you tried riding the camel with your leg draped across the saddle, rather than astride, like the last time!