It was amazing to sleep in a bed again last night! After three straight nights of sleeping in trains, in buses, and folded up into weird-smelling couches, there’s no place like home – or at least, my new adopted home for the next few days, the Canadian Hostel. My big private room ($20 a night) has two big beds, one of which is being used for my luggage, and a coffee table and farsha-like mattresses on the ground for kneeling on. It has air-conditioning and a window that looks out onto a landing with places to hang my wet laundry – I brought enough clothes, however, that I’ve only needed to use that for my towels.

Where was I? Coming back from Aswan on my luxurious (comparatively speaking) first class train ticket. As luck would have it, I ran into two guys, almost my age, that were coming back from their own sightseeing weekend in Aswan, an American and a Mexican. The two of them had been living in Egypt for the past 9 months as Christian teachers up in the north of Cairo (“the really dirty part, if you can believe it,” one told me) and over the first few hours of our northward ride, we talked nonstop about life in the Middle East for foreigners, and how policies and treatment of foreigners differ between a famous country like Egypt, and a country like Jordan that westerners need to be told, “Yeah, it’s the one between Israel and Iraq.” “oooohhhh.” I shared my pizza with them, and they shared their soft drinks and chips with me in return. To my surprise, they told me they actually liked the bribe/tip/palm-grease system of bakhsheesh, something that I am fervently glad has not made its way northward to Jordan. “It’s just a matter of learning how to use it to your advantage, when to pay out, and when you can safely ignore blatant requests for tips.” They had a point of course; at some point during my time here in Jordan, I passed a threshold where I was no longer getting cheated or ripped off by taxi drivers. It’s not like I need my Arabic skills in a taxi, so that can’t be it – instead, I’m sure it’s just something in my mannerism that says, “This foreigner with the silly hat actually knows where he’s supposed to be going.”

After arriving in Cairo at 9 the next morning, I took a brief nap in my room, relaxing in the comfy aforementioned bed. But, the tourist in me rebelled against my lazier half and forced me to get out of bed around 1 so that I could continue my sight-seeing. I peered at the tiny map in my Lonely Planet book and wondered what I would have time to attempt in the remaining daylight hours. The Coptic section of town wasn’t too far away, only 3 subway stations south of me, and I decided it was time to see some really old churches.

I had to take this picture of the museum and courtyard through the bars of the gate before I went in

I recalled that Haitham had told me that the word “Coptic” actually means “Egyptian” in their original language. “They like to say they’re the descendants of the original ancient Egyptians, and all the Arabs just migrated in from Saudia,” he said dryly. “Like it’s their country or something.” Of course, in the centuries since the Holy Family returned to Judea after fleeing to Egypt from Herod’s persecution, a lot has changed. Coptic as a language is only spoken by a few, and only during church services, like how many Muslims outside of the Arab world “know” classical Qur’anic Arabic, but only enough to recognize it during sulaah prayer time and repeat some phrases back.

At the heavily-guarded gateway to the Coptic Museum, I was forced to give up my camera yet again and leave it in a box at the counter. It was getting to be a regular thing. Back in Luxor, I had asked Haitham to query about this strange hatred of cameras to one of the guards. “It’s all because of the Minister of Antiquities,” he reported. The Minister, Zahi Hawass, is the one that put in all the photography restrictions, among many others. The guard chuckled. “Personally, we think it’s just because he wants to control every aspect of ‘his’ antiques and every photo taken is one that he can’t charge for.” The guard explained that most other people viewed it as free publicity; the more tourists share with their families and friends, the more likely they were to want to visit Egypt themselves…and spend money. Apparently Mr Hawass disagrees.

The museum was huge and the exhibits were lit with modern fiber optics, much like the museum in the basement of Alexandria’s library that I had seen last week. Descriptions were typed in French, Arabic, and English on professional placards. With the exception of an Italian tour group that rumbled across the creaking old wooden floors like a train, shouting and pointing at things as their guide shouted and pointed back, I was the only tourist there – and the Italian group rushed in and out of the entire thing in about half an hour. I wandered through slowly, my entire visit lasting about four hours. I noted three or four young women throughout the building, quietly seated on the floor with canvases, pens and paintbrushes, listening to mp3 players, slowly and skillfully reproducing the patterns of the ancient frescos and statues that had been discovered throughout Egypt in Coptic holy sites. If you can’t photograph it; you can paint it!

Of particular interest to me were the rooms that slowly chronicled the shifting of the language from Coptic to Arabic. I peered into the worn leather bibles beneath the glass and realized that I could read some of the larger text that was footnoted into the book. Like the Aramaic service I attended with my friend Luay last year, the book had the original liturgy written in Coptic, a transliteration in Arabic, and then finally an Arabic translation. But in huge letters at the top was a phrase which has the same meaning in all languages. I couldn’t photograph it, but I copied it onto a piece of paper so I could (badly) MSPaint it here, in as close to the same text style as what was written centuries ago in shining gold leaf at the top of each book of the ancient Bible.

It says, "Bism al-Ab wa al-Ibn wa al-Rooh al-quds (Ellah Wahad)" which can be easily translated to "In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit (One God)"

I was leaving the last room of the museum just as a guard was making the rounds to clear out tourists and art students from the building; perfect timing. I wasn’t ready to leave the quiet and peaceful Coptic district yet, so I wandered next door to the Hanging Church one of the two churches that bookend the museum. The courtyard and steps leading up into the building were filled with kids and young people of all ages, from children playing tag under the palm trees to high school students and college students studying in the shade, drinking Pepsi from glass bottles, and chatting with each other.

I wandered upstairs to snap a few pictures of the inside of the church, and then outside, where I bought a Pepsi from a bespectacled young man manning the stand for a pound. As I expected, I became a focal point of interest for the youth at the stand, most of whom spoke fluent English without difficulty. Two students, Jon and Monica (yes, both Egyptian and Coptic Arabs!) struck up a conversation with me, telling me about life in Egypt as the religious minority and what sort of dangerous there might be. They both had the usual Egyptian wry and self-deprecating sense of humor, and seemed more or less resigned to the fact that every year, dozens of their coreligionists were murdered or simply vanished, to say nothing of having their livelihoods robbed from them, something that the Egyptian government is quite good at. “But Zach, remember that the meek shall inherit the earth,” Jon chuckled. “We’re about as meek as they come.” The two of them invited me to join their congregation for their Easter service two nights later on Saturday evening, and I told them I would love to come and see it.

Jon shows off his wrist cross, a common tattoo among the Coptic sect. "I got it when I was five. It hurt - a LOT!"

Back at the hostel, I wandered through the halls of the building, searching for people who might have ideas on what I could see next. In the TV room and lounge, I ran into a young man from Thailand who introduced himself as Niknak. He told me that he was interested in seeing the southern pyramids of Cairo, in the complex known collectively as Saqqara. We agreed to meet in the lobby at 6:30 the next morning, and after another quick and tasty dinner of tam’iyah from the shop down the street, I went to bed.

The next morning, the two of us took the subway system as far south as we could possible go to the last station in Cairo, al-Mounib. Niknak told me that although he’d been working as an engineer in Dubai for a year, he didn’t speak any Arabic, because all of the people he worked with, regardless of country of origin, spoke in English for simplicity’s sake. So I took care of the negotiations with Sa’eed, an elderly taxi driver who was waiting for tourists outside of the Mounib station. He wanted 200 originally, but I gently informed him that was the price being asked to come all the way from downtown, and I was able to work him down to 150 pounds instead.

On the way down, Niknak sheepishly explained that his name was actually Assayd, but after studying in the USA several years ago, he realized that he’d rather not use a name that had those three letters at its beginning. He started using Niknak instead, but since the Arabic word “Nik” literally has the same meaning and slang sexual connotation as the F word, he developed a kind of dual naming system for himself. I jokingly told him that he just came to the wrong part of the world to use that nickname (oh no, now I’m using the word too!)

The highways leading from Cairo gradually got smaller, and narrower, and the thin channel of water to our left, an offshoot of the mighty Nile, got darker and dingier. Niknak fell asleep in the back of the taxi, but I stared out into the impenetrable jungle to my right, mere hairsbreadths from my open car window. The air here, although not exactly fresh and clean, smelled like donkeys and other fertilizing materials instead of car pollution. And occasionally, for blurred fractions of a second, the jungle’s trees would part for a moment and I could peer into a slice of field or village and see children playing, men dragging wheelbarrows, and women talking to each other while carrying heavy-looking burdens atop their heads.

I'm not sure what this was, and Sa'eed didn't say, but it looked like some sort of lumberyard - possibly the only reason why there was any cleared room around it!

Suddenly, Sa’eed turned to the left and we passed through the jungle on both sides, with English-language signs on either side of us inviting us to check out native craft markets or supermarkets. It’s a general rule in Egypt – you can tell how close you’re getting to the tourist attractions by how many English-language signs you can see. Within two to three minutes, we had passed through the emerald band of thick forest and burst into the hot sunlight of the desert. The change was dramatic and stark. I craned my neck around, poked Niknak to wake him up, and looked at the almost perfect line of where the water table of the river suddenly dropped off and the trees vanished. There’s never a shortage of reminders on just how much the Nile river was revered.

We stopped briefly at the Imhotep Museum, another clean and well-organized collection of antiques specifically from the Saqqara and Dashur regions. The name of the museum comes from Imhotep, possibly the greatest architecture the world has ever known. It was him who first got the idea to cover up sandy, dusty mounds with stone in the hopes that perhaps they would last longer, and it was from his genius that the first true stone pyramid, the famous Djoser Step Pyramid, was sprung like a squat Lego creation. It was hard to miss the Step Pyramid after emerging from the jungle; it dominated our field of view over the sand dunes.

Sa’eed was completely amicable to sitting in his taxi and chatting with the other waiting drivers, and I told him that Niknak and myself would return after about two hours. We made our way to the gate, and towards a massive stone wall that looked far too well-preserved to be truly ancient, but the little robed Egyptian by the door assured me that it was authentic. We walked through a long hallway of thick pillars I would have called “Romanesque” but of course, I’d be a few thousand years too early. This was the Hypostyle Hallway that people would have entered the complex through, and after a moment, we came out into the large South Court and found ourselves eye to eye with the eldest pyramid in the world.

Guests are ferried in through this entrance, but with a relative absence of fences, they can wander out however they please

I remember when I first saw Petra, I was amazed at how incredibly intact and well preserved everything was. Here, out in the flat and barren wastelands of the edges of the Libyan Desert, I was seeing the opposite effect. Almost everything had entirely crumbled to dust, except for a few altogether obvious attempts to shore up entryways and doors to show tourists where the original buildings would have been. Here was the “House of the North” and the “House of the South,” symbolizing the unification of Egypt, or at least, what remained of them. And here was the Heb-Seb hall (now just a mass of foundations) where Djoser would have celebrated the annual jubilee festival with his citizens.

And of course, there was the pyramid itself, which somehow looked even more huge than even the Great Pyramid of Khufu. Of course that was impossible, and I think my mind merely was able to more fully grasp the size of this step pyramid because of its encompassing scaffolding and other protective structures; things that I was able to put into scale in my mind. The Great Pyramid, on the other hand, is simply too huge for comprehension, and unless I could have seen a flag, or a person, or a soccer ball on its pinnacle there’s just simply no way that my mind could fathom just how large that pyramid was. For example, if you look at the Empire State Building, you know it’s big because you can look at the tiny windows vanishing into obscurity above you and think “That’s a lot of windows!” With the Great Pyramid, you have to look at the huge blocks at its base that dwarf you, and then back up a good 200 meters and look again at its summit and think “oh, and those are the same size up there, too.”

It's interesting to note the size difference between the bricks used here and those used in the Gizan pyramids; it's obvious Imhotep was still experimenting on Djoser's tomb

The heat and scratchy, never-ending wind was starting to get to both Niknak and myself, so we hurried to find temporary respite in the cool small tombs south of Djoser’s complex. These tombs were for people like royal accountants and hairdressers, but like Nefertari’s temple in Abu Simbel many people find them fascinating for their more regular depiction of ancient Egyptian life. Hunting, fishing, drinking a beer with some friends after a hard day’s work…it’s all there, inscribed in ancient stone on the tomb walls belong to “less important” people. As students, we always learn about the impressive might of the ancient pharaohs, which makes it too easy to forget about the entire nation of people that was working below them.

Causeway and Pyramid of Unas: Folks, this is what happens if you don't cover your eternal resting place in some sort of stone shell: it turns into a sandcastle.

As Niknak and I were walking down the narrow causeway leading from the slumped Pyramid of Unas, he suddenly cried out. “Look down there!” We peered down from the causeway, me squinting into the bright and shifting sand to see what my small companion was pointing out. “Look down there…it looks like something with that Egyptian writing stuff on it!” I looked, and sure enough, just peeking out of the sand was the edge of some sort of structure, or door, and I could very clearly see weathered hieroglyphic inscriptions on it. But only a few centimeters were visible; the rest was still buried in sand. Niknak and I ran to the other side of the causeway and, now that we were looking for it, saw two or three other buried doors, some with as much as a quarter of the door showing, and others with far less. Consulting the Lonely Planet, the book acknowledged that scholars believed that there were “still hundreds if not thousands more tombs of lesser nobles and royal workers buried under tonnes of sand in the desert of Saqqara.” It was exciting to think that if we didn’t mind massive fines and being drummed out of Egypt (or worse), we could go down there, bust open an ancient door, and make regular Howard Carters out of ourselves. We somehow resisted the temptation, though, and made our way back to the taxi.

Sa’eed was starting to get antsy to return to Cairo (and Niknak was too, just a bit) but I was eager to see the Mastaba of Ti and Pyramid of Teti before heading back. Niknak was cheered immensely to see the pyramid, as he hadn’t had time to go into any of the pyramids at Giza, so this would be his first one. To be honest, although Teti’s pyramid was just as dilapidated as 90% of the Saqqaran monuments, the underground burial chambers were actual more fantastic than Khafre’s pyramid that I had seen last week, which were almost entirely cleaned out of anything of interest. Teti had dispensed with any of that peasant-like depictions of average life and instead covered the powdery white walls of the inner chamber with countless thousands of tiny, intricate hieroglyphs, more than I’d ever seen in one place before, and then topped it all off by placing himself “below the stars” with a blue and white mosaic above the head of his mostly-destroyed coffin. Niknak said that just by seeing the inside of that single pyramid made the entire journey worth it, no matter what.

Lastly, we went to visit Ti’s famous mastaba, home for some of the best preserved of the aforementioned “commoner art” in a wide, low building now almost entirely buried in sand. Niknak only took a quick glance in and hurried back to the car, but I was greeted by a huge, burly looking man in a turban who introduced himself to me as Abd ul-Nebi (slave of the Prophet). He pointed out a few of the notable carvings on the wall, but when I asked him where Ti himself was actually buried, as I had seen no sarcophagus, he casually glanced about, and then led me to a pit in the middle of the first chamber. It seems that Ti himself had been buried in a hidden lower room that had been discovered some time later, and now Abd ul-Nebi was giving me a private tour of the hidden lower room, lit from somewhere with an eerie greenish fluorescent glow. “Go on, climb into his tomb and I’ll photograph you!” the man encouraged me. Who was I to pass up an opportunity to further desecrate someone’s burial place? I climbed into the large, square pit and waited patiently as Abd ul-Nebi attempted to figure out how my camera worked before getting a few choice shots of me doing my best Karloff impression. Of course, I gave him the expected bakhsheesh, but he wanted more than the 15 pounds I handed him. “This is a special experience!” he protested. I explained to him as best as I could that I would love to give him more, but I was only a teacher and couldn’t go handing out copious bakhsheesh everywhere I went. I reached up and attempted to pat him on the shoulder and told him that to make up for it, I’d direct as many people as possible to visit him…and bring their cash. So there you have it, folks: If you ever happen to be in Saqqara, at the Mastaba of Ti, be sure to ask for Abd ul-Nebi and be sure to say that Zach sent you.

"The Modern Egyptian Mummy, after rising from his unholy tomb, seeks the three B's: Brains, Blood, and Bakhsheesh"

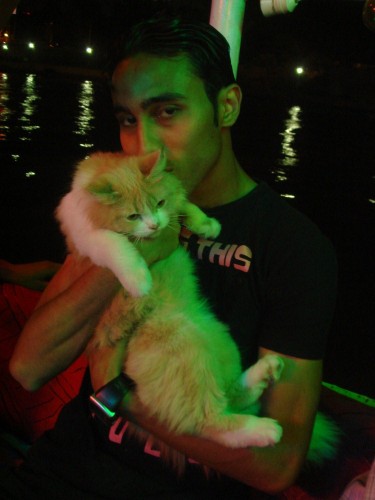

Later that evening, after Niknak and I had grabbed dinner and I had shared my pictures with him, I asked the hostel hosts if they knew of a good place to get a felucca on the Nile inside Cairo. Certainly, they cheerfully responded, just walk to the Nile past the Egyptian Museum and you’ll see them waiting. You can’t miss it! They could have just told me to follow the pulsating, brain-melting Arabic techno music and it would have had the same result. I learned that when a young Egyptian man thinks of “felucca” he means something different than the white-sailed tourist-transporting vessel, instead he’s referring to sputtering, neon-light coated tugboats packed with around fifty Arab young people and another 20 speakers, all blasting music so loudly you’re pretty sure you can actually feel musical notes denting your eardrums. But for three pounds, it was a neat half hour experience.

Of course, I was the only white guy on the entire boat, and so it goes without saying that there are at least 20 pictures of me posing and smiling with various young men on at least 20 different mobile phones somewhere out there in Egypt. I eventually politely extricated myself from the gaggle of curious youth and walked 3 meters away to the railing of the ship and made a point out of becoming very focused on taking pictures of the lit-up city. As much as I love to talk, and attempt to talk in Arabic, it was almost 9 at night and I was more interested in enjoying the river breeze and turning my brain off!

One of the young men had brought his plump, nonplussed cat with him. Although he told me he came with "Tiger" all the time, that didn't stop the cat from making a waddling beeline for a place to hide whenever possible

One of my new friends, Mohammad, and his hijab-wearing girlfriend, told me where I could find a fiteer pizza place as we were all exiting the boat. I had been excited to try it when I was leaving Aswan, but the Americans I had met yesterday morning on the train informed me, after close inspection, that it was not actually fiteer at all. Now, back in my room, I’m eating it as I type and have to admit I’ve never had anything quite like it before. The texture and taste of the dough are what make it special; it has all the qualities of a French pastry or baklava, that is to say; many layers of extremely thin dough held together with a sweet oil. The addition of crumbly meat, cheese, and vegetables made it quite possibly the best thing I had eaten in weeks, and as I told the cheerful bespectacled cashier – I think I’ll have to have it again before I leave. But there’s two days left before I return to Jordan!

No one has commented on this post - please leave me one, I love getting feedback!

Follow this post's comments, or leave a Trackback from your site