Soon after I returned to Jordan from America, I realized that it was odd that although I’d been in the country for almost a year and a half, I had not yet experienced a traditional Islamic prayer, or sulaah. For how much I’ve talked about trying new things, it should have been much higher on my list of ‘things to do’ than to not joined one of my numerous Muslim friends at prayer. Heck, I ate sheep’s brains for Easter last year before I’d been at a sulaah. I figured it was time to remedy that.

The Masjid (Mosque) minutes after completing the morning prayer. The timing is perfectly coordinating so that the sun’s first light strikes the building as prayer ends

Last week, I stopped by my neighbor Marwan’s supermarket and asked him if I could finally take him up on his offer to join him in prayer at our neighborhood mosque, Masjid Hira’a. His broad bearded face broke into a huge smile and he cried out, “of course you can, Mr Zach!” I sat down at his counter for an hour as neighborhood customers trundled around us, bundled against the January chill. He explained to me that the best “first time” sulaah would be the al-Fajr prayer, which is always timed daily to come directly before the first rays of dawn break over the horizon, wherever you may be. I chuckled inwardly at that; I think that everyone in Jordan, be they Muslim or otherwise, has intimate knowledge of that particular prayer when it’s blasted at the wee hours of the morning. He explained that it was best because it was the shortest; usually no more than 6-7 minutes long. “There is rohkta-tayn; two rohkta,” Marwan told me solemnly. “The other prayers in the day – and you know there are five – are either three rohkta or four. This one better for you, for the first.”

He got out a piece of paper and had me write down the exact method of al-Wudthu, the ritual cleansing that devout Muslims carry out before each of the five sulaah. Then he pulled out a battered old Qur’an with a seamed green cover, caressing it respectfully and gently laying it on a cloth on his counter. He smiled fondly at it, and told me that he had this Qur’an since he was a boy and his father gave it to him. As he opened it to the beginning (starting from the right-side, as Arabic is a right-to-left language), he frowned absentmindedly at some scrawls and scribbles in the margins of the first page that looked like a child had been doodling with a pen. “Is not good, this,” he muttered. “Not respectful to write in the Qur’an this way – I do not know where these come from.” I thought about who might possibly have marked up the Qur’an and then forgotten about it over the years…but of course I just nodded politely.

From his Qur’an, Marwan showed me, and then intoned the Surah al-Fatiha, the most important “chapter” in the Qur’an which the Prophet Mohammad (SAW)* instructed must be read before each and every prayer that is made. The first few lines of the surah, which start with “Bismillah al-raahman, al raaheem,” are a common utterance regardless of the situation, merely meaning “In the name of God, the all merciful and ever-merciful.” The rest was more of a jumble, but sounded quite pleasantly melodic. Technically, music of any variety was forbidden by the Prophet, so the humming chant of the sulaah is really the closest that it gets.

After giving me final instructions on how to carry myself, where to look, how to stand, and what to wear (the latter was pretty much the only thing that he said was up to me; the rest is fairly complex), I took my leave of the supermarket as Marwan happily told me, “As-salaamu alayk, akhi!” – peace be upon you, brother! However, because of scheduling issues and some mix-ups, I wasn’t able to finally attend until just this morning.

I rose at 5:15AM, when Marwan called my mobile and quietly told me to prepare myself in wudthu and meet him at his house gate next to the supermarket at 5:45. In the distance through my window, I heard the “waking adhan” calling all Muslims to arise and prepare, crying out dramatically, “Prayer is better than sleep!” I hadn’t eaten much the night before, and I was careful to avoid any alcohol. I was trying to take “purification” seriously in all things. Technically, even flatulence ruins the purity of wudthu so I didn’t want to take any chances by eating a big meal of falafel and hummous and fuul – three foods which are all made from beans!

The water’s hot and ready and I am awake far too early. Oh well…”prayer is better than sleep” after all…

I put on my blue dishdash robe (this makes the third use of it in a year, I believe) and went into the bathroom with my piece of paper with Marwan’s specific instructions clutched in my hand. I stumbled sleepily on the edge of my flowing robe and banged my caving-sore hip on the door frame – but successfully refrained from saying anything uncouth for the sake of the situation. I stared down at the paper at what I’d written down as the warm water filled the sink in front of me. I took a deep breath, and tried to perform the following as gracefully as possible.

- Wash each of the wrists, first the right and then the left, with three circular motions

- Cup water in your right hand, suck it into your mouth, swish it around three times, and spit it out

- Suck water into your right nostril and then blow it out. Repeat three times. And then repeat with the left nostril (note: this one was really hard to do without coughing and choking)

- Wipe downwards across the face with upwards-facing palms, from forehead to chin. Repeat three times

- Using the left hand, wash the right arm from wrist to elbow, inside and out. Repeat three times, and then switch hand and arm

- Taking some water into palms, run hands from hairline to the nape of the neck and back the opposite way, keeping hands tight to the hair

- Clean out ears with the tips of each index fingers, from top to bottom

- Taking some water into palms, run hands from the nape of the neck around to the front of the neck

- Finally, use the left hand to clean the right foot from the toe to the ankle, carefully cleaning between the toes. Repeat three times, and then switch hand and foot

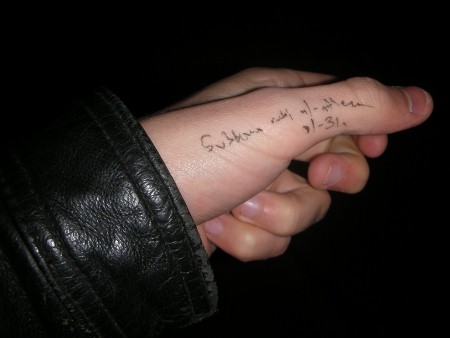

…I looked down at myself after I had finished this process and realized that my formerly-dry dishdash looked as though I had just purified it of its sins. I was thoroughly glad I wasn’t wearing a white robe instead, and that Marwan told me to just wear my usual leather jacket into the mosque to keep warm and cover the numerous splashes of water I was now covered with. I tried to review the words of the Surah Al Fatiha in my mind, and realized that I might need to a little help here, in case I was quizzed or something. I scribbled “Subhan rubi’ha al-aduheen x3″ and “Subhan rubi’ha al-3la x3″ in tiny letters across my left thumb, but I knew I didn’t have time to write anything else. I glanced at my clock and realized that one thing remained – Marwan had pointed specifically to the silver cross I wear on my neck and said, “You need to take that off when you pray in Masjid; take off all silver and gold.” He explained that it wasn’t because it was a cross, but just because almost all jewelry is forbidden for men. I slipped off the necklace and walked downstairs and and up the street a few meters to wait in front of Marwan’s dark doorway.

I don’t think this is forbidden, but I didn’t exactly advertise it to Marwan either!

I heard his deep voice intone above me from a window, “Zach” and then I heard the thud of sandal-ed feet on the stairs leading towards me and within another moment he was next to me, walking quietly and serenely in sweater, corduroy trousers, and a denim jacket. He smiled a quiet smile and asked me if I was ready for al-sulaah, and I shivered from the morning cold and nodded in assent. Without another word, we joined the flowing, shuffling stream of men next to us in the street and entered the warm glowing gate of the Hira’a Mosque, kicking off our shoes on a small footwear-barrier as we did so.

The room was about 15 meters square, with white tiled walls and several chandeliers hanging over the praying men. The most eye-catching thing was the carpeting, which looked to be a special variety embroidered to appear in the shape of a couple hundred rectangular prayer rugs, each connected to the other and all pointed towards the front of the Mosque, towards the holy Kaa’ba stone in Mecca just one country away. The religious leader, the imam, had already began the Al-Fatiha in a quavering and nasal drone, which I recognized with a small smile as the first time I had heard the man’s voice without amplification through the speakers attached to the mosque, every day, five times a day. I couldn’t see the man, but his thin-yet-powerful voice clearly echoed off the tiles in front and to my left – somewhere behind the tight mass of men that had gathered in the front of the chamber, heads already bowed in the sulaah.

There were about sixty men in the room for the early-morning al-Fajr prayer, an impressive number in my opinion for just past 6 in the morning. Marwan stepped quickly into the rear of the two lines of men, stared directly down at the star-shaped embroidery on his prayer “rectangle” – as I guess I can’t call it an individual rug – and quickly gestured with his hand for me to get next to him and position myself identically over the rectangle to his right. I was a little slow on the uptake, especially since he couldn’t speak out loud and tell me what I was doing wrong, but I realized that the man behind me was waiting to take the square to my right and I quickly leapt into place.

Marwan lifted his hands and made the universal Islamic guesture to represent “prayer” – putting the tips of his index fingers to his ears to emphasize that he was ready to listen to the word of God. He then quietly folded his arms over his stomach, right hand over left, and angled his head downward, gazing at the ground. I mimicked him exactly, and stared down at the perfectly-positioned tiny pen writing on my left thumb while mentally repeating the two phrases in my head.

The two rohkta are just different instructional Surah readings, but of course before each one, the Fatiha needs to be read again, and the well-known act of falling to one’s knees, pressing the forehead to the thick carpeting for 20-30 seconds, while repeating surah to and Subhan to oneself. I won’t deny that I was completely lost for almost the entire session and I couldn’t have told you what surah I was listening to the imam read, although Marwan told me later this evening they came from Luqman the Naml surahs. I didn’t know what to say or think, so I just tried to pray to myself, and I actually did find myself thinking in Arabic for a few minutes. I certainly wasn’t reciting surahs, but I asked God in Arabic to help me and my students have a good lesson that day and for the Lord’s guidance. At the end of the miniature service, which really did only last 8 minutes, including both of the two distinct rohkta, all of the men quietly got to their feet, adjusted their robes and hats, shook some hands and smiled, and left the room, grabbing their sandals as they left. That was it – the entire process was as simple as that and the prayer was over.

Marwan was waiting for me outside the masjid when I came out slightly after him (it took me a little bit more work to slide my unpracticed feet back into my shoes) and asked me what I thought. I truthfully I told him that I enjoyed it, which I did. It was a very peaceful experience to be there with all those devout, praying people, listening to the ethereal drone of the imam while praying (or attempting to in my case). Marwan hopefully asked me if I was interested in converting to Islam, to which I explained to him again that I was just interested in learning more about Islam because I was curious and found it enlightening to study. As we chatted in front of his gate to his house, he reminded me (for the fourth or fifth time) that he had been personally responsible for two conversions. “I have two friends from Britain, they came to visit here in the Jordan, and went with me to Mosque, and asked and studied about al-Islam. I was with them when they spoke the leh illih leh ullah wa Mohammad al rasoolullah. Now they are great wise men and are followers of the God in Islam.”

When I told Wajih and Khalil at work that I had been to al-Fajr, Khalil, being a Muslim, was of course excited and told me that if I had any questions about Islam, I should ask him – a similar sentiment voiced by all of the other vocational training teachers that happened to overhear my slow and precise Arabic description of what it was like. Wajih swiveled back in his chair and told me to be careful. “Why?” I replied, to which he told me an unfortunate anecdote about a friend’s father, who happened to pray at the largest Mosque in England while he was visiting London while randomly standing next to another unrelated man who happened to be on an FBI no-flight watchlist. This man was under surveillance and some pictures were taken – many of which happened to include his hapless neighbors. Wajih warned me that ever since, years later, this completely innocent man had been unable to get through an airport security check without being taken out and subjected to an extra 2-3 hours of questioning and interrogating. “But what does this have to do with me and this mosque here in Amman?” I asked. Because, replied Wajih, that mosque next to your house isn’t just a masjid, it’s also a theological school for Islam. And Philip told me that it is known to have a teacher of Radical Islam in its employ, who is known to be under surveillance. So be careful where you spend your time and remember who might be watching you.

Oh. Well, in that case…

I’d like to address any FBI or CIA agents who might be reading this blog: I had no idea about any of this and I’m just a random scholar who happens to be interested in different religions. If you have any other questions for me, please just drop me a line (I assume you have all my email addresses already) and let’s get any possible flying-related unpleasantness out of the way before I have another flight – what do you say? You know how to reach me.

I went down to the Bel’ad with Haitham this evening to have some argeilleh and eat some falafel from Hashem’s restaurant. I had already told Haitham about the morning’s experiences, and he chuckled knowingly at what it was like for me and told me that it was brave of me to try new things. At Hashem’s, a little Egyptian man was frying the falafel out front and he glanced at me, automatically greeting me in English with the standard, “Welcome to the Jordan” that every foreigner here is guaranteed to get at least 3-4 times a day. I nodded to him and then answered him in Arabic, “Your words are very kind, master, but I want to ask how much two falafel sandwiches would be?” He gaped at me, then said to Haitham the equivalent of “Well, he speaks Arabic – now I’m embarrassed.” I laughed as Haitham told the little man that I didn’t just speak Arabic, but I had also been to the sulaah al-Fajr that very morning. I thought the man’s face would break in half from the huge smile that spread over it, and he grabbed my hand and pumped it enthusiastically. He then started speaking very rapidly to Haitham, and I only caught half of what he was saying. He then turned back to me and said in Arabic, “Welcome to Jordan, Welcome to Hashem’s, and God Willing, soon we welcome you to the Religion of God, al-Islam.” Haitham looked rather uncomfortable, so we bought our sandwiches and left the beaming man and the restaurant behind and returned to the bustling street.

I asked my friend what the falafel-maker had said, and Haitham confirmed my guess that the man had told him “not to miss your chance! You speak English and you have a gift – it is your duty to help your friend come to Islam. You have to save his soul! Save him! Save him! You must not miss your chance!” Haitham cleared his throat awkwardly, and explained that on the Islamic radio broadcasts, the imams always used that phrase when they commanded all English-speaking Muslims to use their talent to work for the salvation of the souls in the West.

From the way he shuffled his feet and didn’t look me in the eyes, I figured that he was worried that I would think that he was trying to convert me like his religion technically demanded of him to do. However, I was more interested in the realization that when you look at it objectively, Islamic teachers use the same exhortations as Christian pastors and priests. Instead of being offended the way that Haitham feared, I was truly touched to see the similarities between my religion reaching out to save souls, and Islam trying to do the same to mine. I’ve realized and come to embrace the fact that when someone tries to convert you or asks you to come to Mosque, or Church, or Temple with them, it’s not because they’re trying to upset you or make you uncomfortable – it’s because they genuinely care about you and your soul and they want you to feel pull on your heart that they do. What would the world look like if for once, all the xenophobic Christians and Muslims looked across the aisle – or ocean – and saw the truth about the “other side” – that they’re really just trying to save each others’ souls?

——————————–

*Sallallahu ‘Alaihe wa Sallam (S.A.W.)

“May the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him.” This is said whenever the name of prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) is mentioned or read. The equivalent English phrase is usually abbreviated as S.A.W. (peace be upon him). (Source)

Zach I really enjoyed this! You painted the picture beautifully. Wa’lla! Ana ba7ibo. Wa ana ishtagalak!

What degree range is a “January Chill?”…like 60 degrees? 😉

Ha! I’ll have you know that (in the Fahrenheit scale) it gets as cold as 34-37 before the sun comes up in the morning. Certainly it’s more than cold enough to see your breath!

Beautiful blogpost. I am really happy you saw the picture of Islam that a lot of people miss out on!

Brave man; your plogposts always caught my eyes.

And you’ve beautiflly finished the paint, I loved it so much.

Dear Friend:

How can you be contacted, apart from the comments of your posts?

We share common goals. The website provided, display of which is by all means authorised and encouraged, has especially been created to denounce the “banning” of the illegality of the war on Iraq as an acceptable topic for dissertation by a professor at a graduate programme of Law in a British university.

Your experience in computer matters and organisational tactics maybe required.

I apologise for posting this message; however, I had not been able to find any other means of contacting you.

Your history is impressive! Maybe we will meet one day.

John

I really loved your experience; the way you portrayed it makes it seem so amazing and peaceful…You know inspired me to write about a little peom about the prayer of Dawn.O the lost prayer of dawn! ok it is done now , you can have a look!