A car lightly sideswiped Haitham as we were groggily crossing Talaat Harb street after grabbing our sandwiches this morning. It spun him around and he fell back onto the curb, panting slightly. I’ll give the driver credit; he stopped in his car, opened his window, and peered out at us silently. I should note that he was watching my reaction, not Haitham’s – he barely glanced at the man he’d hit. When I didn’t run at him clutching my passport and roaring “lawyer” he steadily accelerated away and vanished into the heavy traffic. We certainly weren’t in Jordan anymore. And I thought the traffic in Amman was bad!

So what should two foreigners do in Egypt first? The pyramids, of course. Haitham didn’t want to take a taxi, or the metro, or a combination of both, so we found the local’s bus system hidden under a highway overpass and waited about half an hour for it to slowly load up with people so that the bored-looking driver could stop chain-smoking and start driving.

What can you say about the pyramids that hasn’t already been said? It was exciting to see them slowly rise like mountains, shimmering in the Cairo haze, over the tops of the apartment buildings. Specials on TV never show them within the context of the ever-growing city around them, which made it all the more unreal. Then we got off the cramped microbus and came crashing back to the reality of the poor Giza district around us. Within minutes, three different men had tried to haggle with Haitham to have us rent horses to ride around the enclosed, fenced-off desert surrounding the pyramids. Haitham was all for it, but I took one look at the bony, sad-looking nags penned up in the shadow of the pyramids and tried to convince him otherwise.

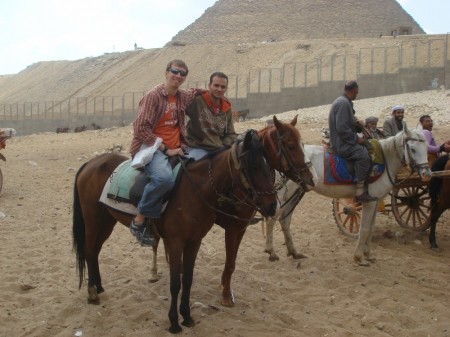

In the end, we ended up renting a couple horses for an hour, and unwillingly found ourselves renting a “guide” as well, who helpfully pointed to the large things dominating the skyline and said “These – pyramids.” Haitham’s horse seemed slightly healthier, but my horse kept tripping over things – rocks, sand, its own legs, air molecules – which I found somewhat alarming. We had to pay this guide’s admission fee into the pyramid site, and then it was time for my first fun experience with Egyptian pricing.

Egyptian historical sites love foreigners’ money. They really do. And good ol’ President Hosney Mubarak (yes, that’s the same root triconsonant as the American president, Barack means “bless” and Mubarak means “blessed”) really wants to help out his Egyptian countrymen (who all are united in hating his corrupt guts) so he makes sure that while the prices for historical sites are written out for foreigners in English, clearly stating that the pyramids are 60 pounds to enter, written next to it in Arabic is the 2 pound price for Egyptians and all other Arabs. I assume that the vast majority of foreigners who visit the pyramids don’t read Arabic, so they never know the price difference.

Haitham thought he could get me in for the price of an Egyptian; he explained that he had done the same for his friend James, who had lived in Jordan a few years ago and traveled to Egypt with Haitham. I figured it couldn’t hurt to try, so I hid quietly around a corner as Haitham went up to the counter to easily secure two 2-pound tickets, with الهرامات (al-Haramat, the pyramids) written on it. Meanwhile, my eyes meandered over the never-ending flow of tourists in, out, and around the security checkpoint-scanner gate. A couple of people whom I thought were Wisconsinites stopped nearby, and looked at the ticket prices on the wall. “Sheiza” one of them muttered disgustedly, proving that they were probably more likely to be original Germans than ancestral Germans like my countrymen.

The “I’m Arab” ticket didn’t work. Haitham passed through without difficulty, but then the burly officer/bouncer grabbed my ticket out of my hands and waved it at me, and then at Haitham when he tried to pull me through. “Does he look like one of us?” he grated to Haitham in Arabic. “Where is this foreigner from?” I answered him in Arabic, “I’m Jordanian, can’t you tell by my accent?” It was, after all, noticeably Jordanian. The man cursed under his breath, puffing up his medal and badge-covered chest. “I’m just a poor student traveler,” I told the man in Arabic, trying to calm him down, but the word I used for poor, “miskeen,” is more frequently used for downtrodden and people with bad luck, and Haitham told me later that he thought the man was going to punch me in the face in anger. As I went back to get my foreigner-priced ticket, Haitham told me that the bouncer kept cursing, told him that foreigners were never miskeen compared with Arabs, never deserve anything but foreigner pricing and that Haitham should be ashamed of himself for trying to “help” me around the 30x higher pricing. Well then!

He had a point, of course. If Haitham hadn’t suggested trying to get me in for cheap, I wouldn’t have bothered with the extra hassle of rule-breaking. Paying the equivalent of 11 USD to see the most famous ancient ruins in the world was not going to break my budget and I didn’t protest any further. It wouldn’t be the last time he’d try to “help” me, though.

We rejoined our horses and Farghut, our knowledgeable guide. Haitham wanted to immediately burst into a gallop, but I was still feeling sick, since even before leaving, and I loudly protested the thought of forcing this poor, near-death animal and myself to suffer any further by heaving ourselves across the sand and probably crashing headlong into an ancient monument. It’s true; you practically trip over ancient monuments out here. Farghut appeared amused with this suggestion and suddenly slapped my horse on the rear, completely without my suggestion that perhaps we should wait on this idea. “No! No! NOOOOOOOOOOO” I screamed – in a very manly way, as my horse’s joints suddenly creaked into action and I was flung forward in the saddle. Egyptian saddles, I should note, are not like American “beginner” saddles and I would not consider myself anything but a beginner at horseback riding. I was in for the ride of my soon-to-be-ended life.

My horse, Naa’eema (which ironically means “Grace” in Arabic), suddenly decided that she wanted to head for the hills and the small clumps of pyramids that surround the smallest of the “main” pyramids, the Pyramid of Menkaure. I discovered that I could either hold on for dear life to what passed for a saddle in Egypt, or I could attempt to steer. I settled on the former for my hands and bellowing “ARRGHHHH STOP OH GOD STOP” for my voice. As we careened towards the field of rocks that used to be part of the smallest of the pyramids, I had images of the horse tripping over them (she was still falling over herself as she was galloping) and me being hurtled, helmet-less, onto the ancient stones. “Idiot foreigner killed by pyramids and clumsy horse – should have paid more” the headlines would read. But Naa’eema seemed to realize that she would be heading for the glue farmer if she tripped over rocks this large and suddenly halted, almost dislodging me from my bat-like clinging to her saddle anyway.

Farghut and Haitham were still trotting a few minutes behind, pointing and laughing at me. As they caught up, I spurred Naa’eema back onto the “trail” to follow them. Suddenly, a couple of young, barefoot Arab men flew past us on horses, whooping and snapping their whips into the air. “Oh no,” I groaned as the ever-obedient Naa’eema responded to the sound and started to speed up. At least this time my adrenaline levels were prepared for the change in speed and I was able to steer her towards something that wouldn’t kill us both. I hollered and leaned back in the saddle, using my own body weight to try to rein in the snorting mare. As I slowed back down to a trot, I heard a moaning wail from behind me, and turned to see Haitham, looking unusually pale for an Arab and perspiring. It seems his horse had been just as responsive to the whipcracks and he had enjoyed his first taste of a desert steed’s full-out gallop. He wasn’t laughing anymore, but I sure was. He was actually impressed, though. “You looked like a real American cowboy just then, leaning back in the saddle and waving your hat in the air. And you screamed like a man, too.”

Although we’d paid for an hour with the horses, at a price of 40 pounds per horse (plus 20 extra for Farghut), it seemed that he had been counting the time we had been waiting in line as part of that hour. Lesson well taught, you crafty Musri, you. Haitham wanted to pay for another hour, but I felt like I had been broken in half and was more than happy to dismount and kiss the well-trodden sand. I had my first lesson in “bakhsheesh” from Farghut. As I wandered away from my horse to snap pictures of the pyramids and the Sphinx, I heard our leathery companion call out to me angrily. He stomped over the sand too me and held out his hand, demanding that I pay him more money. Haitham was standing behind him, shaking his head. “I already tipped him; he’s just being greedy now.” I gave him another 5 pounds, doubling what he’d received from Haitham, and sent him on his way.

Bakhsheesh is, unfortunately, a necessary part of the tourist-wrangling Egyptian life. They’re unpaid by that aforementioned saint, President Mubarak, and in fact I’ve been told that they have to pay the government for the right to conduct business that, a few generations ago, would have been public roaming land for their camels. I didn’t begrudge Farghut the extra dollar, certainly not – the two dollars from Haitham and I would be all the pay he’d receive for that hour – but I wish that they could just add it in on the beginning instead of forcing tourists to haggle over it.

Lest anyone think that 2 dollars for an hour of work is unfair, I need to clarify on the cost of living in Egypt. In the foreigner’s restaurant, “Falafela,” where I had bought that morning’s sandwiches, the cost of a single sandwich was a pound and a half – approximately 27 cents. A refillable, old-style glass bottle of Coca Cola is a pound and a quarter. An ice cream costs two pounds. A large apartment costs 60 pounds a night – and that’s for foreigners, mind you. With solely the amount of money I had brought into Egypt from Jordan, I could live comfortably for three straight weeks. Not if I wanted to visit the pyramids every day, of course, but to eat, drink, and sleep, I could do quite handily.

We spent the next few hours wandering around the pyramids, paying special attention to the second of the three, the Pyramid of Khafre, most famous for being one of the few remaining pyramids with its original white-limestone cover. Although there were large signs posted in multiple languages to not climb up the pyramids, Haitham and I joined the multitudes of Arab children and young men clambering about the pitted and scarred stones. Below us, a single police officer wearily blasted away continuously on a tiny little green plastic whistle, shouting hoarsely, “itla! off! itla! off!” and waving his arms at people. After he shouted at us that he’d haul us into the tourist police, we snapped a few more photos and slunk off the massive mound to rejoin the throngs of people at the bottom.

Haitham and I were about to head towards the Great Pyramid of Cheops when suddenly I felt a small hand pat me on the hip. “Mister mister! Mister! What’s your name?” It was a little boy, probably around six or seven. Haitham groaned and rolled his eyes, but I sat down on a half-sunken pyramid stone and the boy clambered up next to me. Within seconds, as if I had given some sort of signal (I suppose I had) I had 10 other Egyptian boys around me, grinning and shaking my hand. It turned out they were there on a field trip with their teacher, a young man about my age, and all of them were curious to hear about what I was doing in Egypt and my work in Jordan. “Will you be our friend?” the students chorused together. “Please be our friend Mister Zakareeya!” Haitham absent-mindedly swatted a kid away who was joyfully hugging his leg. I assured the kids that I was now their friend, which seemed to please them immensely. “You have email at yahoo? Teacher has email at yahoo! Give him email!”

After I had posed for about 5 minutes so that each child could take a picture with me with their camera-phones, the little group trundled off, climbing up onto the pyramid so that they could enjoy the fun game of getting the policeman to whistle at them. Seconds later, I found myself besieged by 6 high school-aged girls, who all wanted to shake my hand and emphatically and repeatedly asked me, “Mister what’s your name?” As I chatted with them on similar topics that the boys had broached, I was astounded by the difference with Jordan. Socially speaking, a female there would never interact with a man, especially a foreign man, and certainly never touch him. But here these girls were, all wearing pretty embroidered head scarves and some of the older ones grinning at me in a slightly different way than the younger ones. “Take us to America with you, Mister Zakareeya?” one asked, and her friend batted her eyelashes at me. A middle-aged man with a bushy mustache suddenly pushed through their midst and pumped my hand. “Very good meet you, Mister Zakareeya!” He fired off a few conversations in fast-paced Egyptian to Haitham, which I was too distracted to catch, but I thought I heard something about “after the marriage.” I gulped and turned to Haitham, who laughed and clapped the man on the back. The man winked at me, the girls waved prettily, and then they too disappeared into the crowd. “What did their teacher say to you?” I asked Haitham. “That wasn’t their teacher, man,” retorted Haitham with definite amusement in his voice. “That was their father.”

We had a few more adventures, like a scalper named Ibrahim getting the best of Haitham and making off with 10 pounds after lying to us and saying that our tickets were good for the small reconstructed “boat museum,” then vanishing after I tipped him for his “info.” I groaned and checked in the guidebook – sure enough, it warned specifically against trusting anyone who said that tickets were good for multiple things or that they could get you in for free. Then there was the time that Haitham and I left to get tickets to enter our favorite pyramid, Khafre, and he had to bribe the attendants with cigarettes in order to let us back in – technically, they were supposed to, but he had to bribe them all the same. Also the time that we got caught up in a crowd of orange-shirted Egyptian orphan kids, about 500 of them, who danced about us waving Egyptian flags and shouting about how wonderful Egypt was as TV cameras rolled nearby. “Election season is coming up,” I muttered dryly to Haitham as they skipped away, clutching posters of their beloved and wonderful president. Finally, when we actually descended down into the Pyramid of Khafre, Haitham and I almost passed out from asphyxiation from the dirty air and the pack of tourists. Serves me right for not paying the extra 40 pounds to see the Great Pyramid’s insides instead – all that was left inside that dirty, foul-smelling and claustrophobic buried tube was a dimly-lit empty stone coffin where Khafre’s sarcophagus would have once sat. I don’t recommend either of the small pyramids as worth the 30 pounds to get in.

As the sun started to set, I we joined a mass of equally sandy, dusty and sweaty tourists trotting towards the east and out of the complex towards the Sphinx, the most famous nose-less embodiment of the Pharoah Khafre. Haitham, tired and in somewhat of a bad mood from having missed the last three Calls to Prayer, was out of breath and was not his usual polite Arab self when a short and chubby Egyptian camel driver offered “cheap camel ride, you ride down to Sphinx yes?” Haitham was short with him, but the driver was insistent, and finally Haitham growled “Fuck you,” to him in English. The little man drew himself up to his diminutive height and said haughtily, “That is fuck you SIR.”

Just like the always say, he's a lot smaller in real life - but they make you stand far away from him!

Haitham seemed to be fairly irritated with our first day’s interactions with local Egyptians. I learned that in his previous trips with his family, they usually keep to themselves, enjoy the city or visit Alexandria, and keep as far away from the tourist sites as possible. But I was enjoying myself. In a tiny convenience store, a dukkan near the Sphinx’s paws, we met a little boy named Abul Rahman who solemnly served us Pepsi, hand behind his back like a waiter, and gave Haitham perfect change from 100 pounds without even batting an eye. Then there was the middle-aged Egyptian woman on the bus ride back to the hostel that had the dubious luck of sitting next to my complaining friend. She drew him a neat little map of the shortest route map and explained the best routes to get from our hostel to various metro stations, and told him, not unkindly, “please remember that not all Egyptians want to cheat you out of your money.”

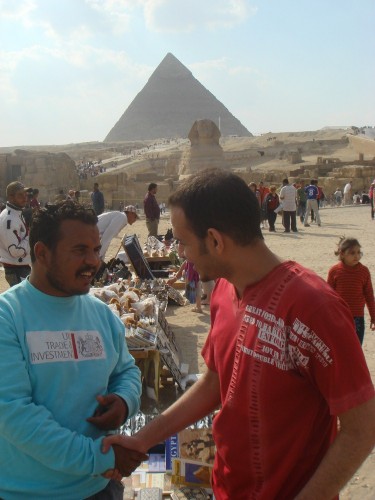

Haitham and Mahmoud, who ended up selling some keychains to him for 15% of what he'd originally asked and was cheerful about it the whole time

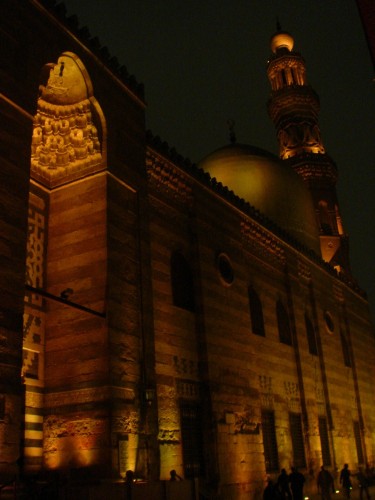

That evening, Haitham and I took a stroll around Islamic Cairo, and sat in the cool dusk under the walls of the ancient Azhar Mosque – the Mosque of Flowers. Set far into the niches and alleys of Old Cairo and away from the highways and shops, it was only us and other tourists and shiookh, wandering peaceful and silently under the rainbow arches of the beams projected onto the mosque’s minarets. We were both tired, but with pepsis and cheap sandwiches in hand, we knew we were ready to face tomorrow – and the crowds of the Egyptian Museum. Imagine: all the same thousands of tourists that had been visiting the Pyramids on its acres of land, now trying to pack themselves into a museum that takes up barely 130 square meters. With this country’s population density, we’d better get used to it!

No one has commented on this post - please leave me one, I love getting feedback!

Follow this post's comments, or leave a Trackback from your site