I have a bone to pick. If you’re going to get a camera, become one of the millions of camera-owning people out there, be it a point and shoot or an SLR…learn how to configure it. And then follow the rules of places you visit and photograph.

I’ve just spent the past day in a rather grumpy mood because of new rules and regulations in the Valley of the Kings that prevent any photography. The rules are from only last year in August, and the guards are extremely strict about them. Basically, all of us that love taking pictures artistically and capturing the nuanced dark angles and shadows that come from standing inside a 3,500 year old tomb are out of luck. Why?

Because of people that can’t turn off their flash. The colors in the ancient paintings and carvings are rapidly fading and being damaged by ongoing light exposure and the millions of schmucks who have taking bland, poor contrast photographs of a bright white wall with some faint etchings and pale colors. Because really, that’s all they’re going to see when they use flash photography in these places!

So, the Egyptian Tourism Authority, over the years, first banned all flash photography, and when it became clear that people were apparently too careless to follow this single rule, they just banned all photography. And recently enough that it grates on me that I’m just barely too late to take my own photographs.

After my last entry, I rejoined Haitham at the Australian Hostel back in downtown Cairo, just barely long enough to grab some dinner and then hurry back to the train station for our 1st-class ticket to Luxor. It turned out that we were sharing a “cubicle” room with 4 other travelers: a couple of Arabs and a couple of visiting Chinese/Taiwanese students. Unfortunately, the six chairs, all facing each other, didn’t recline a single millimeter and we all spent a cramped and uncomfortable (but quiet) night speeding through the desert towards Luxor, the home of the famous tombs of the Valley of the Kings.

We (meaning Haitham) were able to negotiate a private taxi for the day, and a ferry to take us the short distance from Luxor across the Nile River to the West Bank. The price for the day, for the two of us, was a very competitive 120 pounds, although before Haitham worked his magic they wanted 175. It wasn’t until our driver Saleem dropped us off at the ticket booth up in the mountains for the Valley that I discovered that I should hide my camera deep inside my backpack, less I lose it. The weather was hot and dry, much more than we had experienced in Cairo or Alexandria, and I was happy to have a hat and sunblock with me. Haitham boasted that he could tough it out, but it didn’t take long before he would stop at the bottom of hills, panting and glistening in the heat and waving me to “hold up just one minute, please, I’m dying here.”

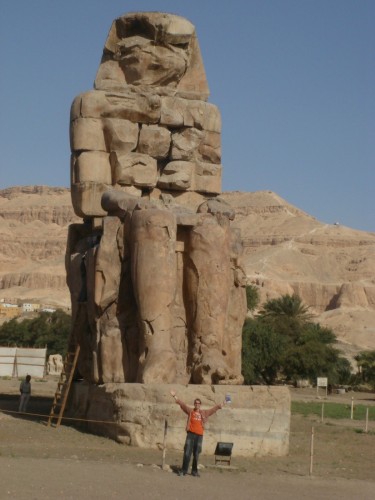

One of the twin Colossi of Memnon near the Nile shore, before entering the Valley. They think that the largest temple ever created was here, but was washed away because of its proximity to the Nile

And hills there were aplenty! The ancient pharaohs of Egypt had loved this location for its easy seclusion and secrecy within the hills outside the ancient capitol city of Thebes, and also because of the orientation of the valley itself allowed the last glimmers of the sunset to fall upon their eternal resting places, something that was just too symbolic to pass up. Thousands of years later, gravel pathways, staircases, and handrails have been added, but if you take the time to actually look up into the hills surrounding you, away from the 21st century chaos that has descended upon the valley, you can imagine that there are still many more tombs waiting to be discovered up there. Or at least, you might guess that if you didn’t already figure that the Egyptian Government already used echolocation and sonar on pretty much everything within a 20 kilometer radius from here.

The ticket booth told Haitham and I that all but two of the tombs were on a “single ticket” concept. Haitham and I pay 2 or 80 pounds, and then we get tickets that are each good for seeing three of the tombs. The tomb guards all have little hole punchers on straps that they use to monitor how many tombs each ticket-holder has seen. So, I told Haitham to buy two, and I would do the same. I figured that if they weren’t going to let me take pictures, this would probably be my last visit to the Valley, so I was going to see as many painted and carved pieces of rock as possible!

As we were buying our tickets, a commotion occurred at the window next to us. A short elderly man with wispy white hair, watery blue eyes was engaged in a heated argument with the ticket seller in perfectly-enunciated Arabic. I didn’t catch all of it, and Haitham told me it was because the man was speaking in Classical Arabic. “He’s a Tunisian albino,” Haitham breathed in wonder. “The ticket sellers are refusing to sell him the 2-pound ticket because they don’t believe he’s an Arab.” The poor man was turning bright red in frustration. “I am a Tunisian!” he roared. The ticket seller regarded him with a bored expression. “Many foreigners can speak Classical Arabic like you do; you’re not one of us,” he replied in Egyptian Arabic. Although it took a few minutes, the man eventually got his proper ticket and was admitted to the site with us. He told Haitham that his own dialect was so vastly different from Eastern Arabic that he has no choice but to speak Classical when he visits the rest of the Arab world, and this wasn’t the first time his Arab-ness was called into question.

The lines of tourists were pretty bad, but not awful. After seeing the crowds at the Pyramids, I had expected there to be a lot of tourists, but I was still surprised at how many people had made it all the way down to Luxor. I should have realized that the Luxor-Aswan route was completely standard for all the tourist buses. We had passed by about 30 in the parking lot on our way in. In one tomb in particular, the spectacularly-hidden final resting place of Thutmose III, not even the electric fans could prevent us all from getting literally slicked-over with glistening sweat. I felt like I had leapt in a lake. Haitham, being medically minded, put his shirt over his mouth and whimpered something about catching all of the airborne illnesses that all these people were exhaling. Normally I regard his hypochondria with wry amusement, but the place was so ghastly hot and humid that I took his advice.

We didn’t bother with the overpriced KV62, or Tutankhamen’s tomb. It was an extra 100 pounds for foreigners and the guidebook panned it as not nearly as interesting as his treasures in the Egyptian Museum. We did, however, venture inside the tomb of his nearest neighbor, Ramses VI, the pharaoh who was buried right above him. This tomb was an extra 20 pounds for me, but it had some spectacular blue-accented paintings and particularly well-preserved carvings of the sky goddess Nuit on the ceiling. Also, the extra ticket requirement meant that it was blissfully uncrowded, with merely a few other tourists strolling up and down its single straight corridor, sandals whispering between the wooden slats and the stone floor. Haitham subtly tried to take some pictures of the sky goddess on his camera-phone, but the second guard appeared from around a pillar as he did so, grabbed his arm, and lectured him sternly on the consequences of taking pictures. He told him that people were fined 100 pounds per picture, the camera would be examined and each picture from inside the Valley would be deleted. In an Arabic aside that the guard probably assumed I wouldn’t understand, he told Haitham that he’d let him off without fine or deletion this time because he was an Arab, but any foreigner wouldn’t be given such a chance.

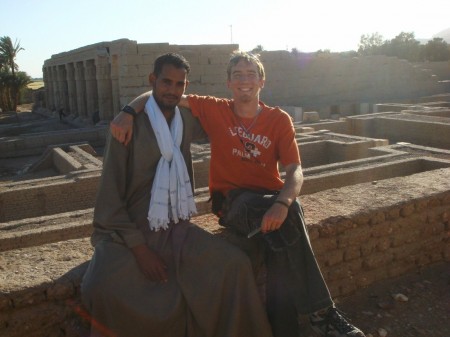

In total, the seven tombs we visited were Thutmose III, Ramses VI, Ramses I, Monthuhirkhopshef, Siptah, the “usurped” tomb of Taworset/Sethnakht, and Ramses III. Try saying all those ten times fast. At the thought of not having to go into any more stuffy tombs anymore, Haitham brightened considerably and was amiable to the idea of climbing over the mountains that separate the Valley of the Kings from the nearby Deir al-Bahri temple, another famous Luxor tourist location. As we were walking off of the beaten path, a robed man came out of the bushes and asked if we wouldn’t mind being escorted. Both of us were rather short with him, knowing that “escort” meant “payoff” but the man insisted that no money was necessary. Optional, certainly, but not necessary.

As we walked up the mountain, the man introduced himself as Ahmad and gave a little more insight into why he had joined us. He didn’t work officially in the tourism sector, he told us, but he came for people’s safety. He told us that he had been present as a young tour guide during the Luxor massacre, he had been watching from the top of this very mountain in horror as gunmen slaughtered tourists inside the Deir al-Bahri back in 1997. It was a very sobering tale. Haitham and I suddenly didn’t feel so put-off about him joining us anymore.

View from the top of the mountain, looking down into the valley over the top of the Ramesseum (foreground)

It was right around here that Haitham discovered that he had an intense fear of heights. When we reached the summit of the mountain range separating the valleys, he gasped in shock and immediately sat down on the ground. Ahmad tried to coax him forward, and in fact ended up practically carrying my friend down the mountain. He offered to carry Haitham’s backpack, and then soon found himself supporting the man himself, as Haitham’s knees were shaking so badly. Ahmad offered to take him back, but Haitham seemed determine to not make himself look cowardly and shakily pressed forward.

It took poor Haitham about 2 minutes to feel steady enough to raise one hand from clutching the rock behind him

At the bottom of the mountain, Ahmad handed Haitham back his bag and stood expectantly. For my part, I bought a couple of hand-painted shale carvings from him. Ahmad told us that he had done the painting as an apprentice to his “master” who had done the carving. Haitham gave him a 20 pound note, and we bid him farewell. As we headed through twisting and shimmering desert heatwaves towards the dark arches of the Deir al-Bahri, I turned back and and saw him watching us from halfway back up the mountain. He was an extremely fast climber, and I felt safer knowing that he was watching over the valley – armed with a mobile phone now, unlike 13 years previous.

No one offered or asked us about tickets, so we just walked up the long sloping pathway and directly into the monastery. We realized a little bit later that our mountain journey had expelled us directly into the Deir’s complex, but compared with the Valley of the Kings, security and attitudes were relaxed and we were able to wander among the pillars and dozens of Osiris statues in various stages of crumbling dignity. Haitham sat in the shade of one of these statues with a couple Arab guards and drank tea with them as I ran about photographing things, exulting in being able to take my camera out of hiding again.

The final visits on the west bank of the Nile were to the Temple of Seti I and Medinat Habu. Haitham elected to sit them both out and instead stayed in our rented car with Saleem. I journeyed through these last two almost alone; they were both practically empty compared with the Valley of the Kings and Deir al-Bahri. Of particular interest in Habu was how deep the pharaohs had carved their hieroglyphic names into the stone. The deep-seated belief that eternal life for the rulers could only take place if their images and names were intact was everywhere in Habu. Ramses III, its primary builder, was paranoid about this theory and made sure to carve his image and name into the stones so deeply that you can easily fit your entire hand into the cuts in the rock.

One of the more grotesque carvings in Medinat Habu depicts Ramses' scribes dutifully counting up slain enemies via their dismembered hands (upper queue) and penises (lower queue)

In Seti I’s temple, a tall young robed man lightly glided over to me moments after I’d bought my ticket. He introduced himself as Ahmad, guide for the temple. At first I was completely nonplussed, assuming that this would be more of a “handout” and less of a “guided” experience, but this time I was completely wrong. Ahmad knew everything about the temple, and led me from room to room, explaining what each image was of and its theoretical purpose in glorifying the god-king Seti I, father of Ramses II. He could even recognize the subtle differences in headdress between father and son, both pictured in the carvings on the wall, and also the basic and constant hieroglyphs everywhere in their names and those of the Egyptian gods. He encouraged me to take as many photos as I wanted, and then took me out on the roof of temple and pointed out the ruins of a nearby Christian church, and how we could barely glimpse the top edges of the Deir al-Bahri to the west (I think that’s what I was looking at, at least). We exchanged phone numbers and I gave him 20 pounds, the largest bakhsheesh I’d ever given. He deserved it, though!

Saleem drove Haitham and I back to Luxor. “Wait a minute,” I asked Haitham in confusion. “How did we just drive over here – I thought we took a ferry to get over to this side of the river!” Turns out that the ferry is just for tourists, but Haitham hadn’t been interested in paying another 20 pounds for the return trip so he told the driver to cut the crap and just take us on the highway bridge across the river. I had barely enough noticed when we drove over the bridge across the Nile; our Saleem’s friend had joined us and was eagerly asking me to review some documents he had recently published onto his travel guide website.

As Haitham and I extracted ourselves from the taxi at the foot of the Temple of Luxor in the center of town, he confessed to me that he was beyond exhausted from all of this tomb and temple viewing. “I’ve decided to return to Cairo tonight, I won’t be joining you to Aswan and Abu Simbel,” he explained. He tried his best to convince me that I would be wasting my time to go all the way down to the south and see more tombs, but I stood resolute in my wish to see Egypt’s southernmost wonder. He spread his hands in defeat, and the two of us walked in silence through the quiet city, eating cheap ice cream (a mere single pound) and watching the gulls circle above. It took several hours to get our separate train tickets, his first class back to Cairo, and my second class down to Aswan – apparently the only computer that could deal with south-bound trains had burned out. I was tempted to force my way past the security guards, crawl over the counter, and replace the power supply myself.

Our final trip of the evening, to Haitham’s reluctance, was the beautiful Luxor Temple – by night. The sun had set an hour ago when we bought our entrance tickets and approached the eerily-lit Sphinx-lined pathway to the temple. The Call to Prayer sang out behind us from a nearby mosque, and statues of Ramses II loomed over us, glowing from below with yellow light and their crowns lost to our view into the darkness. My camera was almost entirely drained of battery power at this point from the past two days of usage and my inability to charge it last night on the train, and the video below was the last thing I was able to capture.

“You know, this temple at night is my favorite thing about the trip,” said Haitham thoughtfully, smiling up at the ancient pillars and unconsciously rocking back and forth in unison with the Call to Prayer. I chuckled and told him that finally hearing him say that made me feel better about the whole thing. I knew he wasn’t going to change his mind about joining me for tomorrow’s trip to Aswan, but I didn’t mind – I know now that our interests lie on opposite sides of the vacationing spectrum.

The road from the Luxor Temple led directly to the train station. I could see it behind me as I entered, framed in the man-made valley of main street buildings as I turned to wave goodbye to Haitham. The temple and its pillars almost seemed to be shimmering in a blur of red stone and yellow light. And then the door closed behind me and I was alone.

You are sooo lucky! I have always been fascinated by Egyptology. But the more I read, the more I know I have to wait some years before going – can’t picture myself in a tomb and a toddler! Such a shame that people are so disrepectful and that you can’t take pics anymore, shouldn’t be that difficult to understand that flashes deteriorate the old paintaings…, should it? bunch of loosers! But well at least you have the pics in your head and a great story as well. you made me remember books I used to read about the Pharaohs and the images I have in my head about the Valley of the Kings… Thanks for a great story! & good continuation…

How strange that Haitham did not realize his fear of heights until he’d nearly scaled a mountain, especially considering the many high places around Amman! I presume you two took an alternate (flatter) route back to the Valley of the Kings from Deir al-Bahri?

Another excellent chronicle of your adventures — I look forward to the next installment from Egypt!

I’m catching up on your blog tonight after too long away. What a great trip. I have to say the echoing call to prayer video at the Luxor Temple was especially evocative. But your descriptions of the people you met- i.e., the “Hefner-esque” fellow on the Mediterranean shore in Alexandria, the albino Tunisian– all fascinating. I’m eager to read on.