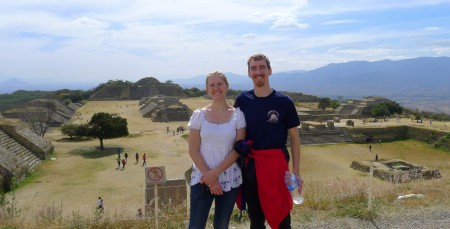

Like most ancient ruins of ancient civilizations, the Zapotec/Mixtec ruins of Monte Alban are filled with big rocks. Built on a large mountain overlooking the modern city of Oaxaca (the priestly/ruling caste of the Zapotec had a thing for being able to overlook their subjects), Alban has a serene, tranquil feel to it even during the post-Christmas high season. Christine and I took a 60 peso shuttle with a bunch of American-Mexicans on vacation to their homeland to the site and were dropped off in a parking lot filled with vendors hawking cowboy hats, combs, and masks. Admission was a mere 59 pesos each, or about 4 dollars – a far cry from the 70 dinar – or was it dollars? – that one had to pay to see Petra back in 2010.

Visually, Alban isn’t as impressive. Exposed to the constant sun and summer rainy season, and to the fact that a modern city is only 15 minutes away by car, a lot of the big rocks are missing, leaving only the foundations of the most important buildings, jagged rocks that if you were to lay on them, would either be great massage therapy or painful torture. The homes of the common people would have been built into the hillside below us in terraces (ancient Mesoamericans love them some terraces) and out of mud or daub, and have long since been eaten up by time and the brambles of cacti and scrubby trees.

To me, Monte Alban could be summed up into three main parts – the central ‘field’, and the north and south raised platforms. We didn’t hire a guide and the English/Mixtec/Spanish informational signs were few and far between, but the empty field seemed to me like it would have been where simple markets and vendors would have set up little tiendas and stands to buy and sell things, with the priestly temples and important political houses surrounding them on the sides. In the middle of the field were a large rectangular raised area which again, was probably for announcements and rituals, but more interesting to me was the angular, offset base off something which the signs thought might have been an observatory. A common theme of every part of the ruins was that it was straight lines, perfectly arranged in north-south alignment. Everything was either squares or rectangles. But if you look here, you can see that the only thing that didn’t fit with this is this ruin, which would make sense if the scientist/priest caste was using it to track particular stars or constellations that didn’t fit with north-south alignment.

We toured the north platform first, climbing up the steps to high points (which originally had shrines and temples on them) and getting some good pictures and wondering to the farthest north points to see some houses. The guide signs referred to almost everything in the far north by “Tomb Number XX” -> after the Zapotec civilization fell apart around 600-800 AD, the Mixtec people slowly moved into the newish ruins and made the stone buildings into tombs for their important dead. The signs used the words “residencies” and “tombs” interchangeably – it didn’t seem like the Mixtec were much into building their own stuff, preferring to use the probably-still-impressive buildings left behind by the politicians and priests. And of course, they seemed to be happy to cart off some rocks from other buildings down the mountain to begin to create what would eventually be the modern Oaxaca, where plenty of Mixtec-speaking people still live today.

After lunch at the gift shop’s tasty outdoor restaurant (Christine eating a tamale and me with Oaxacan quesadillas) we briefly stopped by the south platform, which was more of the same but notable mostly for the massive set of steps that were necessary to climb. It seems common in most religions that steps to climb upwards are needed; in order to keep from breaking your neck, your head must be bowed, looking down at your feet, and not looking up and perhaps disrespectfully making eye contact with the religious icons at the top of the steps.

A common theme with Christine and food here in Mexico has been that she will save a few tortillas or, if I let her, a bit of my meat. She’ll wait until no one seems to be watching her, then quickly stuff everything into a napkin or two and into her purse. We haven’t seen a single cat in Oaxaca. Not even one; street cat or otherwise. But there are plenty of hungry street dogs who are almost always frightened of humans and slink away as Christine inevitably crouches and calls pleasantly to them to be petted. Monte Alban was no exception; down near the parking lot where we were to meet our shuttle bus again 3-5 skinny dogs lounged in the shade. I don’t speak much Spanish, but I can hear people talking about time in Spanish and I’m pretty punctual. Our return shuttle was for 4pm, and Christine let a bunch of other people with stubs for 4:30 or 5 take our spots on the bus – I teased her that it was for the express purpose of having more time to feed the dogs the tortillas and meat she had in her backpack! The dogs were, of course, extremely grateful and one of them even consented to be petted. The others guilty grabbed the food and hurriedly retreated away to glonk it down their throats (glonk is the verb I have created to describe how a dog attempts to eat, snake-like, a big piece of food by just swallowing it whole when they’re in a hurry).

On New Year’s Day, we temporarily left Oaxaca for the only night outside the city, in the small weaving village of Teotitlan, known for their rugs. We specifically came to Teotitlan on New Year’s Day because we had heard that there was a special fiesta in the mountains just outside the village that day only, involving small models being built in little caves, or cuevitas, by the citizens, showing their wishes and dreams for the new years. It sounded interesting, so we braved a very cramped 45 minutes in a “collectivo” or shared taxi – cramped enough that Christine had to sit on my lap in the front passenger seat, and we muttered darkly that perhaps the young woman with the small child in the backseat should have taken our place in the front, instead of two big seats in the back.

We found the village deserted except for one restaurant and a tienda/convenience store. As expected, everyone was at the all-day party up in the hills. We checked in our bags at our B&B for the night, a little place called Las Granadas, and immediately tried to use a borrowed guidebook to find the cuevitas. We completely went the wrong way though, and a little ways outside the city (as we stared hopelessly into the mountains) a farmboy named Francisco took pity on us and offered us a ride to the cuevitas in his pickup truck. We tried to offer him money but he waved it away.

There were hundreds of people in attendance, police, shops selling sweets and (surreptitiously, in black plastic bags,) beer. Apparently this was a religious event – we saw white robed Catholic altar boys seated near a wooden table, in the largest of the “little caves.” To be honest though, the number of “wishes and dreams” that the people of Teotitlan had made was rather disappointing. We saw one or two nativity scenes with the addition of some other plastic and ceramic figurines, but most attention was directed towards two shrines to the Virgin Mary and Jesus that were near the altar. People were kneeling at them, kissing them, and pasting fake money (that you could purchase with a donation to the church near the food stands) to the stone walls.

You can make out the main cuevita shrines at the bottom, with the informal hangouts on the hill above

Christine and I wandered the hills a bit – on some medium sized rocks – while trying to avoid omnipresent sheep and goat poop hidden in the underbrush. People were sitting under blankets, tarps, and umbrellas all over the hills above the caves, listening to scratchy radio stations (yes, some of them were even playing the stereotypical “Mexican Hat Dance”) and barbequing some delicious smelling meats. They were also gathering leaves off of a common bush – for what purpose, I don’t know, but I assume it was for the purpose of making nice smells when burned.

Heading back to the food tents, we surreptitiously purchased a couple of beers and drank them quietly off to the side, watching more and more people arrive before the Mass, or “La Misa” began at 5pm. I had gone with Christine to a Mexican Catholic Christmas service in Milwaukee a year ago and it had lasted for three solid hours – we both hoped that perhaps this wouldn’t take as long, and we were right. Some incense was waved, some comparisons to the caves of Jesus’ live (birth and death) and these “little caves” were made that I could sort of understand, and that was that. We walked back to town as even more people continued to flow into the hills – apparently there would be little parties (nothing huge or public, just more little campfires among friends/families) long into the night.

We stopped for some food at a little taco/hamburger stand that only opened in the evening called “Sam’s Hamburguesas” or “Samburguesas” and as we ate, we could hear the sounds of brass bands playing upbeat music all over town. The high stone walls of the village echoed the sounds all around us as we walked about after dinner, trying to find their source – was there a “public party” for us gringos to attend somewhere?

Finally, we stopped at a house with a large courtyard that the sound was loudly blasting out of. We lingered, hesitating at the door until an elderly man saw us, ran to the door, and warmly welcomed us inside. It turned out that it was a combination church gathering and a wedding, and many of the guests not only spoke English quite well, they were from the United States and here for the wedding!

Usually when Christine and I are asked where we are from, we say “Chicago” because most foreigners wouldn’t know or care about what or where Wisconsin is. However, this turned out to be an amusing mistake because as soon as Christine said Chicago, the group of Mexicans that had surrounded us grinned joyfully and said, “That’s where most of us are from! Which part? How are the Bears doing this year do you think? Are you a Cubs fan?” Christine, thinking quickly, stammered “We’re from…um…Evansville…” and I knew that she meant Evanston, where my brother’s wife hails from, and quickly said, “near Evanston, sorry.” They nodded knowingly at that, and as I made noncommittal noises about the Cubs and the Bears, we were offered Coronas and wrapped bouquets of a special herb that we were to dance with.

The sister of the bride spoke perfect, Midwestern-accented English and told us that because of the auspiciousness of the date 1/1, many people wait to get married or baptize their children on that day, and her sister was no exception. Also, the family who lived in this house (the man who had originally greeted us) had finally received the honor of being named the official “Godparents of Baby Jesus” – everyone in the church congregation got a turn (and Mexican congregations are huge, often numbering in the thousands) – and the waiting list to be the Godparents numbered into the decades. This was a big deal indeed.

Christine and I were beckoned to take our herbs in hand and dance in two gender-separated lines. It was mostly elderly people – somber women in shawls and long dresses, gray hair tied back in buns – and they cradled their bouquets like infants, slowly swaying in a simple step-turn. No one touched each other; Christine and I were more or less paired with other random people as we stepped and swayed back and forth. The band that had drawn us in numbered about 20 people, young and old – and they were quite loud. Christine and I locked eyes a few times over the heads of the tiny old women and sombrero’d men and winced, nodding to the band. The party would go on all night, but we graciously excused ourselves after one beer and headed back to our B&B.

We left soon after the next morning (we had a cooking class to return to, which I wrote about in my previous food-related post) but our fun with Oaxacan Rocks was only just beginning.

I had talked Christine into joining me on a two-day mountain biking trip with a company called Pedro Martinez Cycling, well reviewed on TripAdvisor. It would be a private trip – quite pricey at about $200 a person – and we’d be joined by two men, both named Roberto. The first Roberto was a handsome young man, 27 years old, who would be our companion and guide. He spoke English quite well and was apparently the regularly-contracted guide for the company when English tourists arrived. The other Roberto we called Don ‘Beto at his request. He was a middle aged, distinguished looking gentleman who would be our support driver and follow along in the roomy and comfortable Toyota pickup truck – as we found out, he was the boyfriend of the woman managing the Pedro Martinez desk, who in turn was the sister of Pedro himself. Roberto jokingly told me that Don Beto had definitely gotten hooked up with the right family for the relatively cushy job of slowly driving an airconditioned car for a day and a half. Keep in mind – the average salary for Mexicans is about $4 a day, and we’d be handing over $400 for two days!

We didn’t mind though, as the two Robertos took excellent care of us. All of our food and drink was paid for, and they had booked us rooms in something called a “Tourist Yu’u.” These “Yu’u” places were kind of like combination restaurants and hostels, created by the Mexican government, for the purposes of encouraging more tourism to small but important villages like Santiago Apaola, where we were staying the night.

Here’s where you can “follow along” where Christine and I if you like. Thanks to the Runkeeper app on my Note 3, I tracked both days of cycling and you can download our route for the first day here. It’s a KML file – you can load it into Google Earth by following these instructions. We started off about noon on a dusty desert road, wide enough for two cars. Apparently this was the only road to Santiago Apaola.

It was a rocky, gravel road. And here’s where the “little rocks” in the title come into play – they don’t call this “mountain biking” for nothing. I thought I’d done some mountain biking in Jordan before, but it was nothing compared to what we’d be experiencing the next two days. We had been given some thin gloves and were riding well-maintained bicycles with good suspension, but we were in for some definite soreness in our arms and hands.

The first day wasn’t so bad for me, but it was quite hot and sunny and Christine told me that it was pretty unpleasant for the most part. There weren’t many trees to shield us, and some of the uphills had rocks the size of softballs strewn on them, necessitating a very cautious and low-gear ascent. The downhills were fun, and Roberto, dressed in typical biker spandex, would shoot past us like a bullet to wait at the bottom. Christine rode the brakes hard, and I was very cautious on corners – of which there were also many, as we were switchbacking up and down small mountains ceaselessly.

There were some beautiful vistas, some curious sheep and goats, and some watchful sheepdogs who snarled at us and almost took a chunk out of Christine’s shoe once. At least, unlike Jordan, we didn’t have to worry about uneducated village children tossing rocks at us – the response from the farmers and villagers was a drowsy stare, slight smile, and a muted “Buenas tar’es” We saw some absolutely massive agave plants – I had no idea that two types of liquor, Oaxaca’s famous mescal and the less-known pulque, were made from the cacti. The plants grew large over a year or two, before putting up a single central stalk which could get as tall as 20 feet (that we saw, at least!) and a single flower – after which, it would die and become hard and blackened.

We reached Apaola at the end of long, arduous downhill with plenty of switchbacks that you might be able to see in that KML file. We could see the village and a massive cave cleaved into its closest mountain below – and at times the road, strewn with basketball sized boulders, was no more than a foot from a 300-400 foot fall into the valley below. I wondered and hoped that my brakes would last the trip. Christine joined Roberto and I at the bottom 10 minutes later.

As we chatted over lunch, and as the evening drew out, then dinner, we learned that the village was extremely important to the Mixtec people because their creation legend stemmed from a waterfall at the foot of the village – hence why the Yu’u had been built. One of their Gods, a snake, created the waterfall from his tail; at the top of the waterfall, a tree grew. And from the tree’s fruit, the first humans were born.

The Yu’u twin-sized beds were dorm-room-like, but serviceable enough for a single night. The Robertos encouraged us to eat and drink as much as we liked; we didn’t ask questions but figured that the amount we’d paid for the trip was more than enough to cover what we could credibly consume. The following morning at 7 the four of us hiked a mile or two down what felt like about 3 flights worth of stone and wood carved steps to see the massive waterfall fall down that same distance. As it’s currently winter, the water was at its lowest levels, with much of the basin exposed and water-carved into interesting curved whorls and arcs. The walls of the basin were completely coated in green, fuzzy plants and small trees, in stark contrast to the dry brown and faded green we’d seen in most of the region thus far.

That would soon change, though. After breakfast, the bicycles were loaded back into the truck so we could climb out the other side of the Apaola valley (Roberto said that although he’d done the climb on his mountain bike before, he didn’t recommend it to anyone but gluttons for punishment). 20 minutes later, we were mounting back up and plunging into a dense, thick wood. Here’s the GPS track for the second day. Everything was lush and green – and we figured it was because our elevation was high enough that we were in the clouds themselves. It was a cool morning, around 11 when we started, and Christine was in high spirits. As it was Sunday, well-dressed farm families were walking up and down the hills, briskly. As I paused to wait for Christine on top of a high hill, two old women passed her as she was trying to bicycle up it, which caused her to look a bit crestfallen. I reminded her, though, that those women had likely been climbing that hill every day for the past 60 years or more.

The forest was beautiful and the clouds were literally all around us. Finally, Roberto stopped, called Don Beto and the truck forward on his 2-way radio, and recommended that Christine and I take to the truck as a half-hour long uphill was ahead of us. Christine accepted, but the weather was cool and pleasant and I wanted to show off a bit – so I told him I’d try for the hill. While it was challenging – I’ll admit I was ready to throw in the towel about halfway through – eventually it turned into an incredible foggy downhill with Roberto and I playing tag on the cliffs as we zig-zagged back down the other side of the mountain into a small village. Right on cue, Don Beto caught up with us as Roberto and I chugged water bottles in the village square, and the clouds parted and the sun came out.

Christine got back on her bike and we continued on, shucking our windbreakers and donning sunglasses and sunblock instead. We had dropped some altitude and it was heating up – although still not nearly as uncomfortably as the previous day. After only 5 miles or so, though, Roberto warned us that the best downhill was coming up – and it was going to be quite rocky. “It’s easy at first, but it gets harder.” He said it would take an hour just to make it down to the village of San Juan Bautista, which seemed a bit mind-boggling – an hour for a bicyclist to get down a hill?

It was no lie, though. The road started out about as rocky as the worst of the mountain switchbacks yesterday had been. My hands vibrated uncomfortably against the handlebar, and small sores started to open up along the tops of my thumbs – unfortunately, the gloves weren’t quite enough for my long fingers. But then it got worse halfway through. The yellow limestone changed to hard white granite and the gravel disappeared entirely. Instead of gravel interspersed with rocks, I now had bedrock with rocks on top. I’m not kidding when I say that blood started trickling from my thumbs – nothing major, but the pain was definitely real. Roberto was sympathetic, and told me that I should ride the brakes less. He was right, but when you’re dropping around 4,000 feet over a period of 10 miles and the constantly switchbacking roads are carved right into the cliffside – can you blame me for riding the brakes hard when coming up on a blind turn that a car could appear on at any moment?

Of course, despite the pain, the downhill had its beauty. I stopped for photos many time, trying and failing to capture the wide vista before me. This mountain demarcated two districts in Oaxaca state – one was Apoala, the other that San Juan was in and that we were now gazing over was named Cañada. All over the mountains were thin white lines, looking like spikes growing out of the ground – this was a kind of cactus which was named Oragano. Up close, they were massive – most of them that I saw were at least 20 feet tall, and some looked to be another 10 beyond that. The multi-armed cacti – merely named “cactus” by the Mexicans – were very different than Midwestern American children draw in their notebooks with the uneven two arms – cactus in this area were also in the same height range of 20-30 feet and had dozens of arms. When I caught up to Roberto (who had no problem going down the entire mountain at full speed) at times, he pointed out some trimmed shrubbery lines in certain places on the mountain and explained what they were. Mexican villages are often completely independent of state or federal taxes, but in return they have no services, either. Instead, the village council will assign every resident a task every year or two, called la carga, and you’re expected to do it as part of your duty. For example, some people might become trash collectors. Others might have to measure water reservoirs. And in the case of these cleared lines, some might go out occasionally and cut lines in the trees, bushes, and cacti to delineate where your village’s boundary ends and the next one begins. Would you prefer that instead of paying taxes? It explained the condition of the roads though – apparently paving, or even just clearing away basketball sized rocks in the road, wasn’t high on anyone’s carga list.

Thankfully, the roads were almost empty. We only saw 2-3 vehicles climbing laboriously up the mountainside – and we had plenty of advance warning, hearing their engines groaning 30 seconds away – and none came from behind, thanks to Don Beto providing unofficial blocking and sticking close to Christine. When I finally rounded the last curve and saw Roberto waiting by the first paved road I’d seen in 28 hours, marking the end of the bike trip, I practically fell off my bike and immediately started massaging my nerve-dead hands, which were throbbing like I’d been using a demented walking lawnmower for several hours. Christine and Don Beto caught up with us 15 minutes later – Christine said that once the road changed from limestone gravel to bedrock, that was enough for her.

That about covers it for outdoors activity and some Fun With Rocks, big and small. I’m currently seated in the waiting area of the O’Hare airport; I’m home now and waiting for the 6am bus back to Madison. Within a day or two, I’ll hopefully have one last post to sum up a few odds ‘n ends from the trip. Sleep can wait; I have a blog to finish!

You tricked me into clicking a geotag you sly fox!