And I thought Swahili was hard! We’ve just spent the past two-ish days hiking the farmland and small village of Endallah, south of Karatu, and home of the Iraqw tribe. If you had told me I’d be sitting down and eat dinner with a group of Iraqis (it’s how they pronounce their tribe’s name) I’d never have guessed it’d be with one of the largest non-Bantu (the majority) tribes in Tanzania.

Our guide was the effervescent, enthusiastic John Karama, who met us at the top of Lambo Hill about 30 minutes away from Karatu. We didn’t quite realize that it would end up being a 3 hour walk – oh how I wished we’d brought more than one bottle of water apiece – but John himself was so warm, talkative, and charming that the time and miles flew by.

John is a tailor, born and raised in Endallah. He has one wife and 7 kids (“only the richest man in town has 3 wives!”) and his trained six other tailors to help the village out. He doesn’t work for Endallah Culture Tours, but when John Mahu asked around the village for people who spoke English and could give a guided tour, he volunteered because he was so proud of his hometown and wanted more foreigners to see it. We were the first Americans that had ever been on the tour, to his recollection, and he was very happy to meet us.

As we walked over the dusty hills, following a group of sheep and goats (who did not want to be petted in the slightest) and some shy kids, John explained more about the word M’zungu, the singular word for Foreigner (vs the plural Wazungu). He wrote it in the dust at our feet with a stick (he did this a lot), then scratched out the Z. “This word? It is Mungu, which means God. Americans and Europeans, you are like Gods to us. I am in the presence of Gods!” We stared at him in a bit of shock. It’s not often someone you met 15 minutes ago calls you a God. He continued, “Climate change? You did it. Nuclear Weapons? They are yours. You can enter any country in the world. But you have also given so much to the African people. We have resources but cannot get them from the ground with your machines. You have given us medicine, science, technology, and a worldview. We owe so much to you.” He beamed at us. “Thank you so much for wanting to come see Africa yourself!”

He eagerly told us some stories about how his people, the Iraqw, first met the Masaai. “We used to have many wars with them. For almost a thousand years. The last one was in the 1970’s. We Iraqw have always both had cows and crops, but the Masaai, they only have cows. They accuse us, tell us we are ‘eating with both hands’ and we do not deserve the cows. So they steal them in the night, kill us. We killed them too! We used to live in caves for hundreds of years, us and our cows. We would make a pit in front of the cave and hide it. The Masaai would creep through at night, looking for cows – and then one would fall into the pit and we would jump out and kill him! The others would flee. But then, in the 70’s, President Nyerere wanted us to be at peace. He told us and the Masaai to send a leader to council. They met face to face, talked about things. Then their leader ran into the middle of our villages and said we will fight you no more, and ours did the same to their villages. Now we are getting married to their women, and they are marrying ours. We get along well now! When husband and wife fight, one will tell the other oh no no no! This war is done with remember?!” He laughed and shook his head.

John pointed out local trees and how the Iraqw used them. He knew the Latin names for some of them too – I can’t remember what he called most of them, sadly, as my brain was starting to fry in the noonday heat. But he pointed out the Ebony tree, showing how white it was when it was young, then becoming old and black “like me!” He showed another plant with tiny leaves and said it was used by the medicine makers to fight black mamba and cobra bites. He demonstrated how the bark could be ripped and wrapped around a wound, or chewed and then the saliva pressed into a bite.

We crossed a tiny creek – dried up – that marked the boundary between Lambo village and Endallah village. “Now you are truly in my village. Welcome!” he said proudly. He tore a branch off a tree, then another, and explained that while most people used strike matches now, these two sticks could be rubbed together to make fire. I asked him if that was still used anymore, then, and he told another story.

“The shaman of the village, he uses the old fire making way for ceremonies – like when there is no rain for a long time, or a disease. Everything has to be done with purity. He asks for someone in the village to donate a sheep to the ceremony. Then he does not sleep in the same place with his wife for 3 days – and then another 3 days after the ceremony. He must be pure. He does not eat any food with salt in it. Then on the fourth day we gather together and he kills the sheep, collects its blood in a bowl, and takes a branch of the tree – like this – and dips it in the blood, then swish! Flicks it at the people. We cry out, why God are you hurting us, please forgive us, please! Then the rains come back.” I asked him if he’d ever seen this during his 48 year lifetime. “Only once. For rain at least. We have small ceremonies to resolve feuds in the villages, too. If a man fights with his neighbor, or beats his wife, then he must ask for forgiveness. The shaman tells him what the cost might be, to pay back his neighbor for wronging him, or medical bills for his wife. But he must make the sacrifice to truly show he is sorry. It is the Iraqw way.”

John continued, explaining the importance of sheep in their culture. “When a man marries a woman and builds a home for her, she crosses the doorway first, into the house. Then her dowry, the sheep, follow her inside the home. If they will not cross the doorway, it is a bad sign! Then the man is the third one into the home.” He went on about sheep versus goats. “You see, the sheep and goat are very difference. The sheep eats quietly and does not run around. The goat, it is loud and always yelling, complaining! According to our customs, a woman should be like a sheep – if she has a problem, she calmly takes care of it properly, she does not run around shouting and complaining to all.” Christine and I exchanged a few glances at this, but we didn’t say anything.

We learned a few simple greetings in the Iraqw language, like “Khayn Guamasyita” for me to greet men with, and “Low-why” for general hello. “Dey-lo” for goodbye, and “Sigh-you” for “fine.” The language seemed to have more throat sounds in it than Swahili, and sounded closer to Arabic than Swahili did when I heard John speak it quickly with people we walked by on our journey.

After ten km of walking, we reached John Mahu’s home on a hill above the village center. We ate a quick lunch with Paul, who was waiting for us, prepared by Mahu’s cousin, then collapsed in a mosquito-netted bed for a couple hour nap. There was no connection to the outside world for electricity, but Mahu had installed solar panels so we had LED lighting. For the first time in our trip, we weren’t spending the hottest part of the day in a safari truck with a nice breeze blowing on us. It was HOT. I found myself missing the Wisconsin winter we’d left behind for the first time.

In the evening after the heat had died down, John took us on another, shorter tour, showing the water pumps that Steven, the Belgian volunteer that helped run Endallah Cultural Tours, had started the project for. Projects like this is what our tour money were helping to pay for, since the village’s only river had run dry from global climate change in 2003, pumps were the only way they had year-round access to water.

The dried-up riverbed still has water a few feet below it (for now) so I stopped to help some locals dig it out

John walked us past a row of scrubby trees with finger-like succulent leaves and explained that they were used to make fences; they grew so fast that people would grow them in a line to demarcate a road or property line, then chop them down for a strong, erosion-proof natural fence. “These are Minyara trees, the national park Lake Manyara is named after them. They are used for natural glue, see? They have it in the leaves.” He demonstrated, tacking his fingers together. “But you must not get it in your eyes! It can make you go blind. The only cure is mama’s milk.” We looked at him. “Not cow’s milk or sheep or goat? Only a human?” I said. “Just mama.” he replied firmly. “If you get it in your eyes you must go around crying out mama, mama please help! Then she will come out of a house, just rub a bit on your eye, and you will be good as new!” Christine looked over at me and said, “please try not to get any of that stuff in your eyes or this is going to get weird.”

We walked through town, saw the “pool hall” which had some Iraqw sharpshooters skillfully playing while a football game blared on a tiny, energy efficient TV. A barber cut hair in the room next to it. John pointed out the vegetable market where farmers’ wives sold produce, and the local CCM government office where, from the faint sound of cheering we could hear from inside, the same football game was being watched on a larger screen. Apparently CCM didn’t have much to do around here besides make sure the people liked CCM.

The last thing was the hospital, which had one doctor and two nurses to support the village and the surrounding area. The doctor, a harried looking man named Immanuel, was on his day off, but he and his nurses lived in a building onsite and were apparently sent over from the Karatu Catholic Hospital system in a rotation. He led us quickly through the rooms – the registration, where medical entry forms were piled on shelves and when the official papers ran out, the backs of old school primer notebooks were used. The maternity set of rooms, some of which did not even have covers on the cushions, exposing the bare yellow sponge material. The vaccine injection room, with a partially collapsed table. Immanuel had a long suffering look on his face and simply said “it’s all we have.” The last room, the “men’s recovery room” had a motorcycle sitting in it. I leaned down, patted it, and murmured “don’t worry motorcycle, you’ll get better soon.” Immanuel stared at me, then laughed uproariously for a minute. I had been hoping he hadn’t heard that one before.

As Paul and John chatted in Swahili in the safari truck on the way to watch the sunset from the highest point in the village, overlooking Lake Manyara, Christine and I discussed the village…and the hospital. We agreed that the Iraqw people seemed like some of the nicest folks we’d met on the trip, very genuinely friendly and interested in showing us their town. But that hospital…Christine shuddered to think of delivering a baby there. It was better than nothing, of course. And Karatu town was only 30-60 minutes away, depending on how good your shock absorbers in your truck were, for more major problems. But it definitely made us appreciate well-run, well-stocked medical facilities in the USA.

We clinked beer cans together from the high point and watched a dust storm roll in towards us. Someone had carved “Endallah Culture” in the rock we sat on, and John had brought a container of popcorn for us to eat. The weather, despite the impending dust, was cool and pleasant. But there’d be a lot more walking tomorrow, and Doctor Immanuel had pointed out that dust-caused upper respiratory infections was the 3rd most common disease he had to deal with, so we departed soon after.

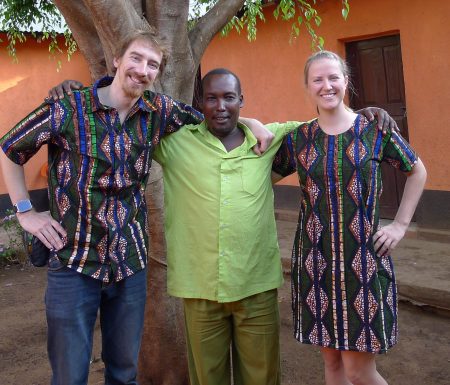

John gushed over Christine’s new kitenga, which she wore around herself as a skirt. “When I see this on you, I think you are a real African! I want to make something for you both, free of charge – a dress for Christine, and a shirt for Zach, in the African style. If you wish, we can stop by Mahu’s store and you can buy fabric, then I will measure you and make the clothes tonight, ready for our hike tomorrow.” We agreed that this was even better than a Tanzanian soccer jersey and bought the fabric from Mahu’s daughter Lillian, a cute, shy 13 year old running her father’s shop under the light of a single bare LED. It was tough to see the colorful patterns in the evening darkness and a single LED, but we managed, and selected a fabric roll with enough material to make a matching dress and shirt. John pulled his trusty measuring tape from his pocket, swiftly took our dimensions, and we parted ways until the morning.

…and that next morning, there was John, wearing his beaming smile and with a newspaper roll under his arm, waving to us from Mahu’s courtyard after our breakfast. “I found this on my worktable this morning,” he said shyly. “I don’t know what it is, maybe you two should have a look.” We took the roll into our room and tore off the paper…there they were, as promised, two comfortable, loose-fitting (in the African style) pairs of matching clothing. We changed into them right away and thanked him profusely as he blushed.

The three of us had one more event scheduled together, a tour of a local banana plantation whose owner had declared it free for walking in for all tourists. John pointed out the common banana types – red Uganda bananas, green bananas, and grey-white “ash” bananas, used to brew local beer with. We saw avocado trees, which surprised us since we always thought they grew on bushes. And John took us on a long walk through wadi-like tree covered valley, strewn with volcanic rock, basalt, and caves. It was quite the hike, but John couldn’t talk nearly as much as he was busy trying to find the right route to take through the boulders and pools of standing water. After we climbed out, Paul and the truck were waiting for us, and we bid John a fond farewell, exchanging email addresses and physical addresses so we could mail him some pictures for the children and young men in the village, and email him the rest of the pictures and videos from our time together.

We hugged him, and the truck pulled away. The last we saw of him and his pale green matching shirt and trousers (which he’d made himself, of course) was him whistling, hands in his pockets, as he walked the dusty two mile road back to his beloved Endallah village.

I also wrote about our day in Endallah. Check it out here: http://christinesuperfly.blogspot.com/2017/01/endallah-cultural-tours-village-visit.html

Endallah is my home village. I hope you enjoyed well. Now days Endallah have changed a lot, There are close support of goverment to her people to get all basic needs. There are lot of potentials that are not yet exploited at Endallah. Come and invest to this area, our Goverment will grant you investment tax incentives