What a great little mini-vacation right before going home for Christmas! Christine and I just returned from four wonderfully relaxing days in Medellin, Colombia – a one hour plane ride from Panama City. We’d been hearing great things about the place for the past four months here and I’d always wanted the chance to visit South America (never been before) so even though timing was tight, we were able to swing 3 flights in less than a week.

What a great little mini-vacation right before going home for Christmas! Christine and I just returned from four wonderfully relaxing days in Medellin, Colombia – a one hour plane ride from Panama City. We’d been hearing great things about the place for the past four months here and I’d always wanted the chance to visit South America (never been before) so even though timing was tight, we were able to swing 3 flights in less than a week.

This past Sunday night was hectic; we had finished our second and final concert with the Cantus Panama choir and had enough time to grab dinner, drop off our Wii U with my friend and upstairs neighbor Denis (he had loaned me his PS4 so I could play Uncharted 4 while he was visiting his girlfriend in Venezuela over Thanksgiving, so I was happy to return the favor for him), and then catch forty winks before being overcharged by a genially smiling taxi driver for a $25 tollroad drive to the airport on Monday morning. I’m semi-terrified about the upcoming legal changes to Uber in Panama starting in April. I might be seeing a lot more taxis and a lot less ubers, unfortunately, so I’m going to have to get better at haggling out prices. I hate haggling in any language, but especially not in ones I lack fluidity.

Copa Air (Panama’s main national airline) served us a nice little ham sandwich snack during our short flight, which was unexpected. Our first step off the plane was a breath of fresh air, like being back in Boquete. We had done little research before our trip (less and less with every passing year it seems – thanks to unlocked smartphones and the internet Christine and I both operate in a “figure it out when we get there” mentality) so with some trepidation, we each withdrew $200,000 Colombian pesos from our bank accounts – or $66.67, since the exchange rate calculation method for us rapidly became “divide the Colombian amount by 3,000 in order to get the USD value.”

Getting an uber was a bit tricky; with my $10,000 sim card and 100MB of data jammed into my S8, three of them cancelled on me before we finally hooked one, a friendly, somewhat acne-covered young man named Juan (who was using his brother’s uber account, a bit disconcerting but at this point we weren’t going to turn him away) who needed to ask us our arrival flight info via the Uber chat system before agreeing to get us. Once we were in the car, he explained in a friendly broken mix of English and Spanish – Uber is semi-illegal in the country and the taxi drivers run a cartel with their buddies, the transit police, to make life hell for Uber drivers whenever they catch them. So Juan needed to pretend that he was going to the airport to pick up “some friends” and therefore needed info about our flight. He told us that if we took ride-sharing services in Medellin again, we should have someone up in the passenger seat so that taxis and the transit police wouldn’t stop him. He said that in Bogota, someone set his brother’s friend’s car on fire for being an Uber driver. Like all Uber drivers though, he pointed out how corrupt and lazy the local taxi drivers were and said that if they provided a better, cheaper service then Uber wouldn’t be so popular.

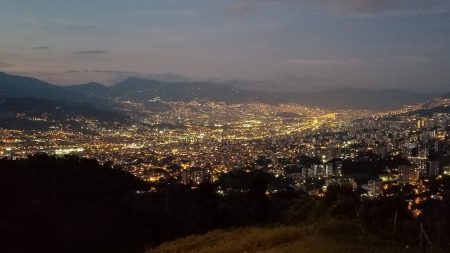

It took about 45 minutes and $17USD to cross the 10km distance from the MDE airport to the actual city, nestled beautifully in a bowl of the mountains. Cool and temperate climate aside though, that bowl unfortunately captured a lot of traffic smog and I could immediately start to feel my throat swell up as Christine casually picked up our “Christmas present” from the security guards at her friend’s building. This friend was the Colombian equivalent to Christine – an English Language Fellow (ELF), assigned here by the USA Dept of State, and she and her husband were gone for Christmas. Knowing that we were interested in seeing the city, she invited us to stay for free at their apartment, but the guards refused to hang onto a housekey for us so instead, we were left “a present” in an envelope that Christine retrieved. The envelope had been opened for us ahead of time (how nice of the guards!) so they certainly knew it was a housekey. But, thankfully, no problems arose from this and we were able to relax and look out over the city to the surrounding mountains.

That evening we got a taste of the city, stopping and getting a delicious hamburger (a mere $16,000 or just over $5.33, far tastier than anything in Panama and at half the cost) on the way to the expansive Metro system. The metro was the one thing in the city more expensive then Panama at 60 cents a ride vs Panama’s 35 cents, but both the routes and the cars themselves are far larger. We headed up to the “trendy” part of town near the University and spent an enjoyable few hours walking with thousands of locals around a Christmas-lit park, watching jugglers and performers, and drinking massive $1 beers. Food and drink wise, I was loving Colombia already. At one point, I made eye contact with a bearded, blonde European looking fellow behind a Belgian Waffle stand and we made finger-guns to each other. He shouted something to me cordially and I waded through the crowd to chat with him. He was asking me if I was Belgian as well and I apologized for disappointing him. I asked how life was and if he’d started this Waffle chain, to which he laughed and said his cousin had, seeing an open niche in the food culture here.

Meanwhile, Christine said a drunk elderly woman had grasped her on the arm, rasped a laugh to her and rapped her index fingers together while pointing at the two bearded white guys. “Paisaaaaanos!” she giggled, and then stumbled off happily into the crowd. I guess we all look alike!

On our way back to the apartment, almost right under our noses, there was a second Christmas festival, also as free to the public as the first one had been, with an incredibly talented young group of gospel choir singers all dressed up in red robes. Like Cantus Panama, they were singing a mixture of English and Spanish Christmas pop music but they had theirs memorized, each duo had a microphone, and they were living it up and practically dancing on stage. It was a lot of fun and we found ourselves wondering – had Christine been assigned here to Medellin instead of Panama, could we have joined this amazing choir? Or were they a university group – hence their amazing talent. We’ll probably never know!

For our second day, we met with a friendly young Medellin native (or “Paisa” as they call themselves) named Sergio, recommended to us by our ELF friend as giving free tours to gringos just for an opportunity to practice his English. We passed an enjoyable 5 hours together, eating $1 croissants and 50 cent coffee as he led us around Moravia, a poorer part of town he grew up in.

We learned about the EPM energy company, a massive hydroelectric company that was apparently the sole provider of electricity to the entire Colombian state of Antioquia, not just Medellin. The vital and active low-income voting population of the area meant that EPM was effectively constantly giving free and discounted services to the entire city – they were the main sponsor of the dozens of parks with huge Christmas lights, for example, and had donated millions of pesos to the construction of community centers in districts like Moravia. The city uses an income measuring metric they call “Sisben” to provide even more services to people who can prove a low income. Sergio told us that in order to get into any museum or park in the city for free, you would bring a copy of your EPM electrical bill which had your Sisben number on it – 1 through 6 (EPM knows everyone in the state’s income and charges them electricity prices based on this, but does not write your income on your bill – just your Sisben). If you have a Sisben between 1 and 3, then you can get into practically everything for free. We saw this written on metros, buses, and parks everywhere – one price for low Sisbens and the disabled, and another price for everyone else (thankfully, including foreigners in that – this isn’t like Egypt where all non-Arabs had to pay a special fee to get into anything, which I always found infuriating since that included fantastically rich Saudis and UAE Arabs besides just the poorer Arab nations)

It seemed to me, from an outsider’s viewpoint, that Medellin kind of had things figured out. A highly motivated and low-income voter base consistently voted in progressive leadership to the city who expanded options for them, while EPM seems to “benevolently” foot the bill. Sergio told us it was a common joke that it was easy to be the mayor of Medellin since you could just count on huge cheques from EPM all the time. However, he also told us that the city was one of the most conservative in the country, vs Bogota, and had some of the worst air quality too. That 350 gangs and small drug cartels prowl the lower income parts of the city outside the trendier middle (where we were living, thankfully) and that the city fudged its employment numbers to include the people in the “black job market” manning shopping carts filled with chopped fruit and little arepa tortilla sandwiches, living hand to mouth and needing to live far outside the city away from their families and taking long bus rides every day. The cartels provide “protection” for their carts during the night…in exchange for large percentages of their profit. Sergio acknowledged that he loved his city and that it was doing many good things for the poor, but it had a long way to go. He said this as we were standing in a weedy lot under a mostly-finished concrete building with large glass windows, but entirely empty. “This was going to be Medellin’s women clinic to provide family counseling…but also abortion. The city continuously votes to not fund any doctors to work here, so here it stands…it could be finished in months if the city would fund it. Our laws supposedly allow abortion, but they haven’t actually been enacted yet.” He shook his head grimly and said that the conservative Paisas were arguing that the more progressive Bogota was enforcing “unwanted” sinful laws on them and that they should be free to be as conservative as they wanted. It sounded sadly familiar to us.

As a closure, Sergio took us up the “garbage hill” to show us what the city could and would do to squatters when it wanted to. Originally flat land in the middle of the bottom of the city’s bowl, it built up dozens of meters high as the city dumped trash there. The poorer families gravitated to the dump (helped by the fact the city’s main bus terminal was just across the river from the growing pile; Sergio called the poor newcomers “economic refugees” from the mountains) and scraped out a living by finding junk and recycling they could resell. But they were squatters, living in dangerous wood and metal shanties on top of each other in a dump. In 2005, the city decided it would try to push out all the squatters and turn the garbage hill into a park. They offered free homes to all the families, with the families that had moved in the longest time ago being given the prime locations. Now with real addresses, running water/sewage (and property taxes!) they would have official access the free public school systems (45 students per class, Sergio added grimly – no one likes our overcrowded public schools) and other opportunities that escaping the slum life would provide. Many took the enticement from the city. But then after the first 300 houses across the street from the dump were spoken for by the “old families” then another 1000 free houses were raised for the remaining families…7km away on a hill with no schools or work opportunities. The public schools would come, the city promised (and they did), but you will have to make your own shops and stores in the area.

Now, the park was a beautiful hill with informational signs describing the 1970’s growth of the dump, the process of “re-homing” the slum dwellers and metal art projects. At the top is a large city-owned greenhouse where the municipality grows flowers to plant in poor neighborhoods to try to encourage more neighborhood pride and work against the “broken windows” mindset. There were a few slum homes left on the hill, though – several of them had large signs in front of them with slogans saying “Resist the City” and “Our homes” – I asked Sergio what he thought of the whole process. He remained noncommittal, saying that while he understood tearing down the slum was for the city’s safety – and beautification – he thought it could have been done better. Personally, I thought it was remarkable restraint on the city’s part to not take this prime chunk of real estate, right next to the river and a metro station, and cover it in condos (that’s what Panama would have done, of course). To instead turn it into a park with art installations. Medellin continued to impress me.

We also stopped by Pedro Nel Gomez’s neighborhood, with walls covered (tastefully) with murals of his art.

After buying Sergio and ourselves a vegetarian lunch near the University as a thank you for his informative tour, Christine and I set out to what he described as the opposite of Moravia – Poblado, the wealthiest and trendiest part of town, a half dozen metro stops southward down the river.

Our eyes were caught by an antique store on the second story of a shop on the main street, and we stopped in to marvel at the massive collection of everything from paintings to silverware to statues to remote controlled cars and old liquor bottles. I saw the number “16” stuck on a cute little porcelain statue of a boy being headbutt by a goat, and thought that for $16,000 pesos it would be a good joke Christmas gift for my parents. To our surprise, the owner said that 16 was just a “code” for him and that the actual price was $150,000 pesos, or $50 USD. I hurriedly set the little figurine down. Christine muttered to me later that the guy must have been a hoarder whose wife had given him an ultimatum to sell. “Sure honey…yep I’ve put everything up for sale…aw darn, no one wants to buy I guess. What a shame. Looks like I’ll have to keep my piles of stuff.”

Christine got herself a haircut from a place recommended by a Panamanian friend, then we stopped by the famous Bogota Beer Company for some national microbrews. As always, the prices were making me weep for joy; a pint of porter or IPA beer during happy hour was a mere $3 and only $5 regularly priced. Afterward, we had far more disappointing and watery/sauce-coated Pad Thai, but for $8 and in South America, I couldn’t really fault the chefs too badly. I was also offered cocaine by no less than three separate people on our walk back to the metro station in Poblado, but they didn’t seem to mind when I politely refused, and then one poor, nervous American-sounding guy who said “whoa whoa, I just want to know if you’ll buy these chocolate wafer cookies, I didn’t mean to scare you!” I wondered what an American was doing out at 10:30 at night in a trendy distract selling boxes of wafer cookies, and theorized he might have been in “hock” to the local drug cartels. No way of knowing.

For our final full day in the city, we wanted to ride the cable car up to the famous Arvi Ecological Park, but after another tasty burger at noon, we found out that the cable car apparently stopped taking people up at a mere 2pm. Stymied, we quickly looked up other hikes in the area and found one – some waterfalls and horse paths southeast of the city near a village called Arenales. One $2,100 peso bus ride later, climbing sluggishly up out of the valley and breathing a lot of exhaust fumes, we were back in the fresh air above the city and walking with locals, horse-riding vaqueros, and their dogs on pretty, mica-flaked stones. At first the trail was marked with orange blazes but after an hour we climbed away from the river and the forest and the blazes disappeared, but the path continued on. A friendly vaquero passed us on his horse and after another half hour we realized we were on his path going directly to his home. He welcomed us to walk through his land, though, and told us there was another waterfall farther on in the hills behind. By this point, Christine was giving me a droll look and we *cough* mutually agreed to give up on finding it after another thirty minutes of walking. It had only been a 5km walk but we had climbed 200 meters up the slopes and got some great views out of it!

Finally, on our last day, we got to see Arvi. The park itself was a little underwhelming, specifically as it’s billed as a free park but only one of the trails is actually free; all the others require a paid guide in order to visit. And the free trail isn’t actually by the visitor’s center at all; an employee told us we’d need to walk a kilometer down a road in order to find it – which we never did, and we were limited on time since we had to get to the airport by 5pm. But the cable car ride itself was wonderful, and partly free – we paid for a regular metro ticket from our Industriales station up to Acevedo for $2,300 pesos, then got a free transfer to the K cable car up the mountain to the east, before paying $5,200 pesos for the final leg of the trip up to Arvi on the L line (which they might as well have called the private Arvi park line, since nothing else was on it but the park.) The cable cars were almost silent except for the chirping of birds around us and the rustle of the trees, and the views were even more spectacular than those from the Arenales mountain the previous day. If only we’d had more time to pay some guides and go on some real hikes; it’s not like the guides were expensive at $5,000 for a couple hours. That’s not even $2 USD.

We had time for one final fantastic lunch at a trendy, new-looking place in Poblado called “Restaurant Brutal” and then we caught a $26 Cabify (a Latin American competitor to Uber) back to the airport, driven by a woman named Lilliana. I’d noticed that there were lots of female ride-sharing drivers, and female metro conductors as well – something I’ve not seen once in Panama yet.

Bottom line – we’ve got to get back to Medellin. We loved everything about it but the air pollution, so next time we’re craving cheap, delicious food in a beautiful mountain city, we’ve got to head back. Bring a facemask for when you’re stuck in traffic!

So glad you enjoyed it!