“Okay, tell me the difference between your two political parties.” Frank paused for a moment and peered over the tops of his bifocals. “You cannot!” It was noon on our first full day in Cuba, and we were taking a walking tour of the old city of Havana. Tamara and Frank had been friends for years – he had been her English teacher when she started her tourism business, and in turn, she had repaid him by selecting him as her clients’ walking tour guide. A thin man with bushy gray hair, a habit of lighting up Cuban cigarettes whenever he had an opportunity (he’d excuse himself politely when Christine and I would rest or get something to eat; he never smoked while walking with us), and a fierce appreciation of Fidel and Communism, he was an excellent introduction to the idealism of the country.

We didn’t start by hashing out politics over beer, of course. In fact, when Andreas dropped us off at Old Habana’s Plaza Central at 10:30am, he demurred any talk of our respective political leanings loudly and expressively when the name “Trump” was first mentioned. We walked down the Obrapia – Bishop’s Street – on New Year’s Day and he pointed out ancient Spanish buildings that had been remodeled in the past few decades, interesting bars and hotels Earnest Hemingway had frequented, and an eyesore of an obvious 1950’s American drab conference center style of building that he said was built right before revolution as the only place in the city with a helicopter pad on top, to shuttle rich tourists from Florida 180km away. “After Fidel, it was taken to be used as a school,” he said with a small smile.

The original Spanish governor’s house in front of one of the city’s five famous squares was pointed out. One of the four streets making the square had its cobblestones replaced with wooden bricks, in order to allow the governor to have his siestas in peace. On the opposite side of the square is the famous ceiba tree where the first city council meeting for Habana was held over 500 years ago. In fact, the city is currently festooned with posters and signs for La Habana 500, which was celebrated on November 16, 2019. The tree is no longer the original, as ceibas aren’t quite that long lived, but if it hadn’t have been New Year’s Day, Frank told us anyone can walk into its little courtyard and give the trunk a rub for good luck.

It was Christine and I who slowly coaxed Frank’s political opinions out of him after we made it clear that we were genuinely curious about them and we just wanted to listen. He had the usual litany of arguments – why are your elections on Tuesdays instead of weekends? Why aren’t they holidays? Why not make them mandatory? Why are banks allowed to control your country? We told him that we agreed with him on many points, and that progressive people were indeed trying to make many of the changes that he pointed out as weaknesses. Your constitution is ancient, he chuckled – 1776? That is like, wow. He described how the Cubans just had their third post-revolution constitution laid out a few months ago, adding things like term limits for El Presidente (no more lifetime Castros), more direct representation for the citizens to elect more levels of leaders instead of only their local alder persons, and more rights for LGBT citizens. Frank agreed there were freedoms that Cuba lagged behind on, like the latter, but was adamant that a constitution that is not modified more frequently to fit changing needs of a population was only going to serve entrenched powers rather than the needy. He also believed that a single party was superior to a two party system, as the latter would only result in constant bickering and backstabbing and not even leadership. It was an interesting discussion; I’m glad we were able to convince Frank to open up to us.

Frank walked us back to the outskirts of Old Havana, and we were handed off to another Tamara confidante, Cuevas the Classic Car Driver. The second of our quintessentially Cuban day, first spent talking politics with bespectacled Communist professors, would be in one of Cuba’s famously restored 1957 Chevrolet BelAirs. Hot pink, no less, which we ahhh’d over, and Cuevas claimed proudly that when he started doing tourist rides 15 years ago, his was one of the only hot pink cars in Havana, “but now, everyone is doing it!” – he was right; it seemed at least half of the restored classics we saw were now an exotic, shimmering Reese-Witherspoon-Legally-Blonde level of pink.

He knew Frank via Tamara, and said that he and Tamara were friends all the way back in high school. Since we’d just had a walking tour of old Havana, and it’s darn near impossible to go anywhere in a car in the crowd, cobblestone streets, we headed somewhere new – to the fort (Castillo de los Tres Reyes del Morro) on the other side of Havana harbor – via an under-harbor tunnel that neatly crossed the narrow bay in a matter of minutes. He stayed with a bunch of other classic car drivers in a parking section and chatted with them, while we wandered over to the giant Jesus statue that a pre-revolution president’s wife had had installed, saw the weird “Che’s House” building (love the huge, restaurant-style logo on the front, guys) and over to the Castillo itself.

As we admired the salt-swept fortress stones, we came across a guy working on another elderly BelAir in the parking lot near the fort. Since the engine compartment was open to viewing, I stopped to check it out. The owner noticed my interest and chatted with me (via Christine’s translations) for awhile. Jorge pointed out the engine, “not original! Korean!” he said. The word “SsangYong” was emblazoned across its metal carapace. He explained that replacing the old engines was essentially required after decades of use in Cuba, and most people, himself included, chose to put in diesel engines if given the choice. Why diesel, I asked, to which the young man grinned a bit conspiratorially and said that drivers all over the country often had contacts within the petroleum import ministries for the military and naval groups via the mandatory military draft for every young man in the country. The luxury taxes on fuel don’t apply to military fuel – especially not black market, skimmed-off-the-top fuel – so it was the “economical” choice to go with diesel.

Jorge looked out at the fort in front of us. He told us that he loved Cuba, but his father had hated the mandatory draft requirement. There were medical exemptions, however, and his dad had bribed a doctor to register him as having congenital seizures when he entered high school. He laughed a little and Christine translated, “too many people make the mistake of registering medical problems right around 18, draft age – they are discovered right away.” Apparently the trick was, though, to pre-plot your draft dodging years ahead of time. The end of the draft age was apparently 25 years old. “All my medical papers and annual exemption verification – into the trash the day of my birthday!”

We returned to Cuevas’ car and continued our sight-seeing, to a small forest that seemed to be covered, slightly eerily, in kudzu or some other creeping vine that made the trees look like a rustling green ocean. Cuevas said his kids called it the “Avatar forest” in reference to the movie. We noticed a group of people dressed all in spotless white walking back to their cars, and Cuevas said we’d see evidence of Santeria worship in this park. Vultures were strutting everywhere in the bushes and trees, and we soon saw why – the Santeria religion requires sacrifice, and feathers and bones of chickens littered the forest floor everywhere. The vultures were going to town on one as we watched. We saw less gruesome sacrifices, too, such a cute little bouquet of flowers surrounded by fruit on the ground, with an un-smoked cigar neatly shoved between the petals.

Other highlights were Fusterlandia, a crazy, awesome looking neighborhood on the western side of Havana where local resident Jose Fuster has covered the walls with artwork made from colorful cracked ceramic tiles. My parents visited the official Fuster house (museum?) when they were in Cuba a few years ago, but unfortunately as it was New Year’s day, it was closed. Thankfully, Fuster has been so prolific in covering his neighbors’ houses with his work, which he does for free, that there was plenty to see in our 15 minute stop. And Cuevas took us back to Tamara’s via 5th Avenue, which has plenty of embassies and homes of ambassadors along it (the United States’ new embassy is one exception, and is located farther east, along the Malecon sea wall’s costal street).

After a dinner on the outskirts of Old Havana of those 50 cent mini-pizzas I mentioned in the previous blog entry, we walked back toward Tamara’s neighborhood in Vedado. Along the way we saw a famously popular ice cream parlor in the center of a large park – Coppelia. We were curious enough to want to go in, but suddenly Christine held up a hand and I crashed into her – we were about to cut in front of a line of 20 or so silent Cubans who were watching us closely, and a security guard was strolling toward us. It must be quite the place – apparently they have capacity limits they’re constantly hitting. We apologized to the waiting queue of Cubans, and continued our walk.

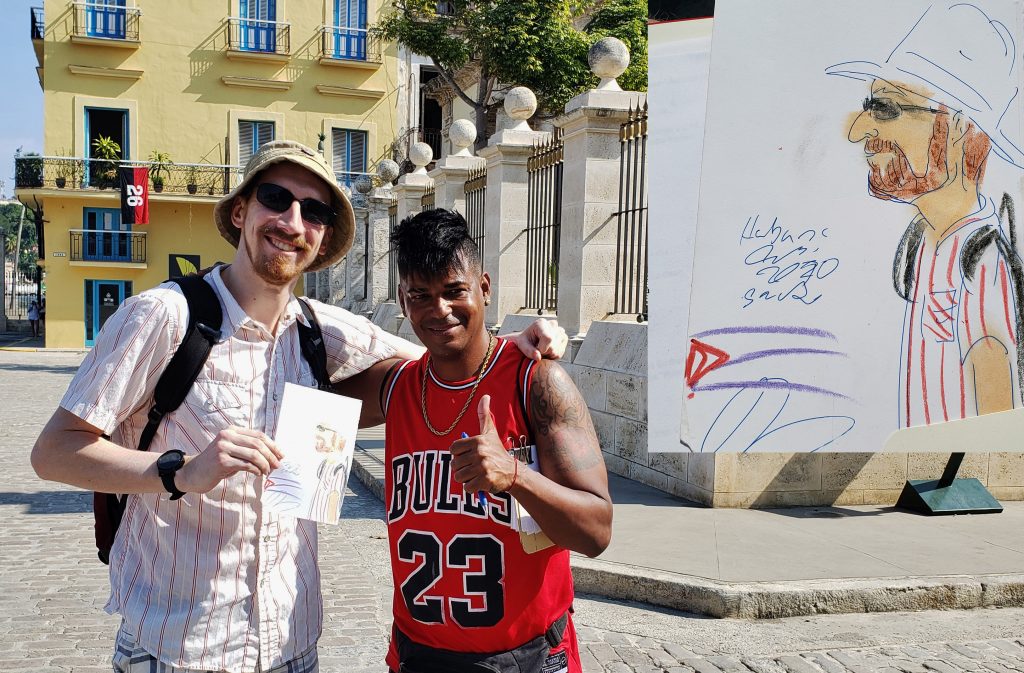

Many of these spacious and shady city parks had knots of people seated on curbs and benches, gazing down at their phones. We had heard about this from Tamara; the majority of Cubans connect to the internet via government-managed non-secured wifi networks. Government stores will sell internet scratch off cards; I was told these dropped in price from 6 CUC per hour, to 5, to 4, etc to the point where now an hour of internet was a single CUC. A young man in a jersey stepped up to us as we lingered, watching the browsing people who ranged in age from pre-teens to the elderly. He asked us in rapid Spanish if we wanted to buy a wifi card for 3 CUC. You scratch off the card to get a code, were taken to a captive-portal page after connecting to the internet, and then you just entered the code from the card and the high speed link (most of the people we saw were watching videos) would last for an hour.

We pondered this entrepreneurship as we continued our walk home. Cubans everywhere were looking everywhere to improve on what the government could offer. This was a country that had only allowed private businesses to exist at all in the past decade or so. We wondered if the government cared that young people were buying lots of internet cards during the day, and then reselling them at nights for three times the government price. They’d certainly care about someone skimming their diesel off the top to resell to local motorists. What was the Cuban government’s response going to be toward an internet-connected, informed, and well-educated population that could see online (for 1 CUC per hour) what the rest of the world had to offer? The new president of Cuba, Diaz Canal, the first non-Castro in 60 years, has a lot of challenges and opportunities ahead of him.

We’re enjoying reading of your impressions of Cuba. It brings back good memories!

Such a good diplomat!

I love all this memories . Thank you