Last weekend, I went up north with Silas and Haitham to see (and as it turned out, participate in) a traditional Muslim wedding ceremony. The two of them had already planned on going, and they invited me along after my depressing-sounding taxi stories from that night. I was a little surprised to receive an invitation from Haitham, since I had just met him a few days before, but he assured me that it wasn’t a problem, that no one would mind my attending. Haitham just told Silas and I to show up at his house in Zarqa the next morning, and he’d take care of everything else.

The bus station the following morning was hot, dusty, and on the east side of town, where I’d never been before. Silas and I shared a taxi over there, and he commented that it was a very different world compared to the west side of Amman, which is filled with western shops, commercialization, and most noticeably, uncovered women. “You won’t see a single uncovered woman in this conservative part of town. It just isn’t done,” Silas commented as the rattling, tiny bus pulled away from the station and roared into the sunrise.

We met Haitham outside his home in the quiet city of Zarqa. As it was a Friday morning, not many people seemed to be up yet, enjoying the day off. Silas and I relaxed in the front meeting room of his house, stretching out our sore muscles from being jammed into the tiny bus (probably broke both my kneecaps). We chatted with Haitham’s father, a cheerful older gentleman who spoke passable English and, coincidentally enough, was a veterinarian, like my mother. Haitham made the two of us some tasty sandwiches (there’s few things better than Arab hospitality) and drinks, and we passed an hour in the cozy little front room, waiting for the bus to Irbid to arrive.

We met up with Haitham’s mother and sister at the bus station, and the six of us took the last seats in the front of coach bus. Thankfully, it was much roomier than the preceding one, with dark velvet shades pulled over all the windows and the typical decorative hangings all over the ceiling. I’ve come to expect an interesting decor inside vehicles here in Jordan; everything from Majid’s little Honda to the massive garbage trucks I’ve rode in have tassels, prayer beads, and thick plush covering all over every surface.

Haitham looked at me with mild curiosity as I pulled out my ever-present camera and started snapping pictures of the wind-swept desert hills and valleys as the bus left Zarqa. “What’s the point of taking pictures of the desert?” he asked me. “It’s just different from what I’m used to, that’s all,” I replied. He gazed out the dirty window into the sands. “Ever since we are little, we are taught that green is good, and the desert is a bad place,” he mused. “Even though we are surrounded by it and it makes up our whole lives, and we cannot escape from it. I am happy when the rains come for a few weeks each year, and when the sky fills with clouds and no one can see the sun.” I told him that in America, we have the nursery rhyme, “Rain, rain, go away, come again some other day.” He laughed at that, shaking his head in disbelief that children could be so flippant about the life-giving liquid.

Although I had been planning on sleeping for the bus ride, Haitham and I ended up discussing Islam and Christianity for the entirety of the trip, comparing interpretations of the holy books and asking each other questions about what makes people good – is it the shame of religion, or a natural impetus for harmony? I played the devil’s advocate here (somewhat literally!) and questioned Haitham’s interpretation, that without religion and the fear of an angry God, the world would be overrun with chaos. I asked him what he would do if he found out tomorrow that there was no God. He considered this thoughtfully for a moment: “In this situation, I suppose, I would try to be a good man and carry on the tenants of Islam. But, as time went on, I would begin to be angry and do bad things because I would have no fear of the next life. This is why we need religion, to be good people.”

When our coach reached Irbid, we transferred to progressively smaller vehicles as we wound our way up into the mountains, until by the time we reached our destination and stopped by a little dukaan (convenience store) for a jug of Pepsi, I felt like we were either going to break through the dirty wisps of cloud, or fall off the side of the cliff we were perched on. Feeling my knees creaking from being jammed into the truck of our most recent transportation (a minivan) I got out and stretched. A few pickup trucks rattled by, packed with wide-eyed children who stared bug-eyed at me, mouths agape. “Yeah, you might as well get used to people staring at us while we’re here; this definitely isn’t Amman,” Silas muttered behind me.

After a few more minutes and another couple hundred meters up the mountain, we came to the site of the festivites. The minivan squeezed the six of us out with a tired gasp, and rumbled away down the road, as a crowd of people descended on Haitham’s family, leaving Silas and I awkwardly staring at the ground for a few minutes until one of the men, a muscular man who introduced himself to us in perfect English as Mohammad, and invited us down the short hill to his house where the party was taking place.

Almost ceremoniously, Silas and I were led through a crowd of forty people, all of whom rose to their feet when we approached and lined up to shake our hands. Smiling and nodding, they grasped my hand and spoke, “Ahlan,” “Asaalammu Alaykum,” “Ahlan wa Sahlan,” “Marhabah,” as I tried to fumble my way passably through returning the proper response to each different greeting (it’s like a confusing game!)

At the end of the line, we met the patriarch of the family, and learned that this wasn’t just a wedding, it was a double wedding. The Old Man (which is what I’ll refer to him respectfully, since I never did catch his name, and usually fathers, especially older fathers, are merely referred to as “Father of (son’s name)”) was marrying off the last of his sons, of which he had 10 others and two other daughters. “Alf Mabrook!” (A thousand blessings!) I stammered to him, awed by this prodigious progenitor who was now smiling up at me. Of all of the Arab men I’ve met so far here, he seemed to fit the wise-and-venerable-grandfather more than anyone else: he wore a long, flowing blue robe, traditional hatta (headdress) bound with thick leather cords around his forehead, and a short, neatly-trimmed white beard. His face was incredibly weathered and lined, but as he beamed at me and pumped my handed happily, I quickly saw that they were all smile lines. As we all sat together, drinking the hot spicy coffee that I had been first introduced to at the Sheik’s residence, the Old Man never stopped smiling congenially at the throng of well-wishers around him, laughing, and shaking the dozens of hands that were being continuously proferred to him in blessings.

Mohammad and the Old Man were neighbors, and the party was split between their two houses, with us men sitting outside in a long patio in front of Mohammad’s residence, and apparently, the women cloistered within the Old Man’s house (I could hear them occasionally, and less occasionally an ornately covered head would peep out the door to look up at us. As I listened to Mohammad explain to Silas and I, there had been hundreds more people earlier in the day for lunch, but now people had gone home to prepare for the festival in a few hours. Suddenly, he recalled that we hadn’t eaten yet, leapt up, and led us four latecoming men (Haitham’s mother and sister having instantly vanished to join the other women when we had arrived) down the hill to the Old Man’s welcoming room, where a huge plate of Mensaf was set in front of us, complete with the delicious sour cream sauce, thick fluffy yellow rice, roasted peanuts, and roasted chunks of lamb (bones and all). Mohammad sent another man down the hill with us, who silently seemed to have the sole purpose of slicing up the lamb into smaller chunks and pouring more cream sauce over the rice.

Moments after eating, the “parade” began! People started pouring over the hill to congregate in the road outside the Old Man’s driveway, surrounding two young men in pinstriped suits that I deduced were the two grooms. Shouting and cheering, the crowd began singing and chanting, and the two men were lifted onto the shoulders of their older brothers and were carried briskly down the street towards the south.

Little children in t-shirts and sweatpants cavorted around our feet as Silas, Haitham and myself followed near the back. I quickly found out why as we started to enter the village’s commercial district – every time we passed a dukaan a man would come out with a box of candy and chocolates and rain them down onto our heads. The children seemed to be completely insane for these treats – flinging themselves under our feet, stomping on each others’ hands to reach them first, and shoving for them like they were little diamonds instead of 10-cent candy bars. A lot of kids had also brought little aerosol cans, which I was wondering about until they raced up to the grooms and sprayed long arcs of white foam that smelled vaguely of soap and jasmine directly into their paths. Suddenly, it seemed like the Jordan mountaintop was covered in snow as the light breeze blasted the light foam in all directions. Even in the back, I quickly found myself coated with foam like it was my high school graduation again, and I did my best to try to prevent it from landing on my camera lens. The adults laughed indulgently, and the grooms didn’t seem to mind much either about their jackets (although after about 10 minutes of repeated spraying one of them looked like he was profoundly wishing their mothers had kept the little ones at home).

Here’s a video of the “wedding party” heading towards the center of town, singing and in some cases, drumming. Haitham told me that they were basically singing to God to look favorably upon the marriages and that they would please Him, and to protect the new husbands and wives.

When we got into the main village square, we joined about fifty other men that were already there waiting. They had rolled out a booming sound system at ear-shattering volumes, which was playing Arab Techno (for lack of a better descriptor) that was repetitive, but catching and fast-paced. The “wedding party” was merged into this group, for a total of around 250 people in the square. The video above shows the traditional Arab dance, “Dapka” which looks easy, especially when they’re starting slowly like in this video, but is a lot tougher to do properly without stomping on people’s feet and looking like a total idiot. The younger men at the festival (numbering about 30-40) really took it to another level, with intricate coordinated stomps to the beat, raising their left feet together and bobbing forward out of the line for a heavy, rhythmic *thump* all at the same time. They would also practically flip each other, playing around. There was one guy in particular that I recall who was really incredible at this, dancing like a Russian: keeping his upper body perfectly still while his legs were doing this incredibly fast and flailing jig.

I don’t have more videos of Dapka because they hardly ever let me leave the line to go grab another Pepsi! It seems like wherever I turned, there was another guy gesturing me to join the line. Although Silas and Haitham participated a little bit in the dancing, they quickly found spots at the sidelines to watch the dance and the tall, bearded imam-types firing off fireworks above our heads. At one point my attention was grabbed when a man ran into the crowd and fired off a dozen pistol rounds into the air. “Those are just blanks, right?” said Silas to Haitham. “What do you think?” retorted Haitham with a grin. I decided to stay under an awning for a few minutes, recalling previous stories of people being killed by accidental gunfire at weddings.

It was an unusual feeling to be the center of everyone’s attention, including the two grooms and the Old Man, who were walking around talking to people, but always sought me out in the Dapka line to pat me on the back and greet me. The Old Man seemed particularly pleased to see at the festivities; he kept bringing other older men over to greet me, all the while exclaiming happily, “hoowah amreekee!” (he’s an American!) He would grin happily whenever he saw me, give me an enthusiastic thumbs up and say, “Good! Good! Good!” in his crackling old voice, clapping his hands with joy.

Whenever I wasn’t in the Dapka line, the children would follow me everywhere, staring at me with unhidden expressions of wonder, not even closing their mouths as they gaped at me. I asked Haitham why they seemed to be so enthralled by me in particular, when they barely paid Silas any attention (“I prefer it that way,” he told me later). “You have blonde hair, Silas does not,” Haitham informed me. “Probably, none of these children have ever seen anyone with blonde hair before.” After all, he continued, Westerners didn’t really have any reason to come to this village. He seemed a little embarrassed that everyone was crowding around me so much. “In my village, people are not this annoying,” he said, quickly.

It was a little embarrassing for me too, because the children continuously asked me questions, giggling as I tried to find words in my memory that would fill my limited vocabulary. The adults too, clustered around me, although not as close; it seemed almost like they were trying to protect me from the children, and whenever the kids and I started talking, the adults would hurry up to me, apologizing, and shoo them away. But the little boys always come drifting back within a few minutes, chewing their fingernails and whispering to each other. Several of them seemed to inch towards me, then pat my arm, then race back to consult with their peers. I hate to be guilty of such such suspicion, but I was worried they might be thinking of introducing themselves to my wallet and cell phone, and confided this in Haitham. He shrugged and told me that it was unlikely, that thanks to the Islamic tenant of Zakat Kareem (generous alms), the kids are given money freely by the members of the community when they need it, so petty crime like pickpocketing is essentially nonexistent.

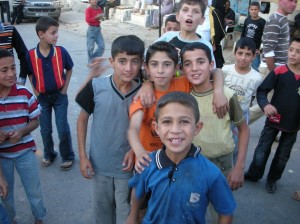

The solemn-faced leader tries to organize his eager gang for photo taking, but Blue-shirt was a little enthusiastic

I felt even more guilty for that worry, when a group of children came towards me again, and then their leader, a solemn-looking little guy with curly hair and an orange shirt, presented me with a gift: a little black plastic bracelet covered with Jordanian flags. He put it on me himself, and then stepped back proudly as I held it up to the dimming evening light to see it better. I was very touched by this gesture, and asked the children if I could take a picture of them. I tried to offer the leader a half-dinar coin, but he shook his head solemnly and melted into the crowd, and his cohorts scattered, giggling, as the ceremony came to a close.

The two grooms were lifted up on a table about 6 feet in the air by six or seven others, and then as the techno Dapka music reached its climactic bridge (for the 80th/90th time) they were spun slowly around a few times as the crowd cheered. The two brothers embraced each other, waved to the assembled village, and smiled down at their beaming father. And just like that, the festival was over, and people began to drift back to their cars. The little boy in orange reappeared again; running up behind me and tugging at my shirt. I turned and knelt down to be at eye level with him. “Hello Goodbye,” he intoned solemnly, shaking my hand and patting the wrist with the bracelet on it. Then he smiled, and ran back into the alley.

But the wedding wasn’t over yet! After another 20 minutes that pretty much involved me semi-passed out in a car, exhausted from two hours of dancing as people ran about, getting everyone lined up for the other part of the ceremony – the grooms and brides were finally brought together and put into a very cute “just married” car, which spent the next half an hour driving slowly around the rest of the village, as about 25 cars and vans followed behind, honking noisily as their passengers (and drivers!) leaned halfway out the windows cheering, waving Jordanian flags, shooting off more fireworks, and waving palm branches. It was an interesting, almost surreal procession – at one point, we were all held up for 5 minutes as a herd of sleepy-looking Nubian goats were herded across the road in front of us by an equally sleepy-looking farmer. For an American, accustomed to weddings with hymns, formal clothes, and a cake at the end, it was almost surrealistic.

This convoy wheeled all around the mountaintop as the night began to overtake the village. Silas, Haitham and myself were jammed once again into the back of a minivan, this time with 4 other men, including the Old Man in the front seat, who graciously allowed me to photograph him. Haitham and I finally found some relief for our crunched legs by climbing halfway out the van’s windows and sitting on the doorframes. “Be careful,” the boy in the video calls to me as I’m clubbed in the back by a kid energetically waving a palm frond (“ouch,” you can hear me mutter). Silas joked with me that the reason they probably have these huge galas of village interaction is to make sure that everyone knows that these young people are married now so that they’re not stoned to death when people see that they’re living together (of course, he was only semi-joking).

At long last, the festivities were over and the majority of the convoy wended off into the darkness, often with four or five children leaning out the windows as they faded in the distance, still cheering and waving their flags. The rest of us found ourselves where we had started; a dozen men and their children sleepily sitting around Mohammad’s porch. For the next few hours, I chatted with Mohammad, Haitham’s father, and one of Haitham’s best friends from home, who was coincidentally named Zakareeya. Later on the evening, the genders finally combined and the five remaining men went down to the Old Man’s house we had strong tea with the women.

Eventually at around 11:30 or so, Haitham, Silas, Mohammad and I adjourned to Mohammad’s house for the night. Mohammad gave me his own cushion (against my protests) and the four of us all slept in Mohammad’s bedroom in the traditional Arab style, on low, padded cushions on the floor with plush ostrich-feather pillows, while the rest of Haitham’s family slept in the next room over. It was remarkably comfortable, and made me feel like a little kid again, when I would take all the cushions off the couch at home and sleep on the floor on my own little nest. We watched a bit of hilariously bad Arab television, attempted to ward off the hummingbird-sized mosquitoes (called nahmous; I felt like we should have been armed with cricket bats) and eventually drifted off to sleep.

The next morning, Silas and I ate breakfast with Haitham’s family and Mohammad, a delicious meal of the expected fuul and hummous, but also tuna and a simply amazing chicken and onion mix that Silas and I agreed was perhaps the most delicious thing we’d had in months. There was also a special tea called Zaerta that Mohammad said came from berries on the mountains, picked fresh. It was particularly nice because it had breath-freshening qualities and kind of fizzed on my teeth. At breakfast, neither Haitham’s mother nor sister wore their hijab (head coverings) like all the women at the party had yesterday. I assumed that it was because they felt comfortable and safe here among old friends, and felt honored that they felt comfortable enough around Silas and I to not wear them.

Before we left, I went out onto Mohammad’s roof balcony and looked out across the land – the mountains, rolling hills and valleys for miles and miles into a far-away misty fog that could have even bed the Dead Sea. “You can actually see Palestine from the roof on a sunny day like today,” said Mohammad proudly, and I didn’t doubt him. The mosque on the mountain across the way was particularly impressive, and everywhere was surprisingly green for what I thought would be a desert, covered in twisted and gnarled old fig trees and a type of cacti I couldn’t identify but was covered in plump red fruits that looked like they would be quite succulent and tasty; if they didn’t also have the capability to impale your mouth at the same time.

All too soon, Haitham, Silas and I were piled onto a little Haifeela (city bus) again and rumbling down the mountain, leaving Mohammad and the dear Old Man behind. Before we had left, Mohammad had given me his cell phone number, telling me to give him a call before I came to the Citadel so that he could be sure to give me the best tour. The Old Man embraced me, and patted my face, and Haitham translated that he was asking if I wanted to stay in the village, learn more Arabic, and become a Muslim. “He says he thinks you’d be an excellent Muslim,” Haitham said as the Old Man nodded eagerly. My two hosts had been so welcoming and kind to me over the past day that I was very sad to say farewell to them.

As we reached the bottom of the mountain and continued our journey back into Irbid to catch a bus directly to Amman and say goodbye to Haitham, I realized something about the beauty of the unspoiled desert, compared with the streets of Amman, which are overwhelmed with garbage trash everywhere you look. It often looks in Amman like someone actually took a bag of trash, wandered into the middle of an empty lot, and dumped it out there. Sadly, even here there was still trash by the sides of the road, in the mountain desert wilderness. But the difference was that here, the trash only extended for a foot on the side of the road, and then it was like looking at land that had never been touched. I took many more pictures as the bus wound up and down the cliffs (“I think you Americans have a word for it; when you go up and down like this in a vehicle?” Haitham said to me. “A roller coaster,” I replied. “Oh yes, that’s it,” agreed Haitham).

The Arabs on the bus stared at me as I took pictures of the hills, much the same way Haitham had done the previous way. I understood now why they were surprised; to them, their sandswept hills were not something to focus on and document…..but I disagreed. I hope that someday, everyone across the world is able to see the natural beauty of their land, be it green or sandy, regardless of where they happened to be born. And then, when they understand it, they’ll want to fight to keep it clean and awe-inspiring for generations to come, for everyone: their children, and visitors like me. “Al-Oordon jameel,” I said to them as I disembarked the bus at the Irbid station – Jordan is beautiful.

An entertaining post to say the least. Are cricket bats readily available in Jordan?

since I can only remember how it was phonetically spelled in your Arabic For Dummies book:

moom-tahz!

Another fascinating experience – how great of Haytham to invite you! Thanks for sharing it.

Wow, you’d better write all yours stories in a book. it’s a really good (but rather long) post. by the time you get back home, you’ll not have anything new to tell people, hehe.

i shared your adventures with mom and that made her recall with what difficulty she had to explain her Arab neighbor that she couldn’t get into her house because the door was locked from inside and she didn’t have the keys. she says she used to speak Arabic well, but lack of practice made her forget what she knew.

Mensaf looks amazing, probably tastes like osh with peanuts, doesn’t it? (the real osh i mean, not the one we had in Boulder). mom will make some good osh for you when you come to Tajikistan!

I don’t know if I’m happier that you’re having these experiences, or that you’re sharing them so vividly with the rest of us!