I would have included this update on last weekend’s trip to Syria in my previous blog entry, but instead my time and awakefulness (new word?) ability consumed by monitoring hose lines all night. So, without further ado (and making this the first month when I’ve done ≥10 blog entries since May 2007) here’s my take on that lovely country “up nort” – Syria.

The back-story behind our trip was that Dozan wa Awtar was invited to Syria back in January to sing in an international choir, with our own concert as well as a “combined choir” with the choirs of Lebanon and Syria, each of whom had their own performances as well. For us Americans (and many Western, war-loving countries in general), it’s a tough time getting into Syria. As in, $131-visa-needing, wait-in-line-all-day kind of tough. But, as Shireen and Hala pointed out, we azjnubeean (foreigners) would be safely ensconced in a protective group of Jordanians so all we needed to do was provide our passport numbers, smile big, and we’d have nothing to worry about.

Except, in my case, there was that mix up last month when I accidentally washed my old passport in my pants, requiring me to get a new one. And a new passport number than I had previously provided. I only got my new number a week beforehand, leading me to get a nervous feeling in my stomach that the entire choir was going to get held up by me and my stupid pants-washing. Even though the 35 of us were together, we were still cautioned that there would probably be a long wait. “Bring a book,” Hala suggested. “A really big book,” one of the other Americans muttered darkly.

We left at 10 from Amman, right after Silas and I nearly had heart attacks when Hala informed us that they hadn’t received our faxed passport copies from the previous day. This meant holding up things for 15 minutes while we ran into a bank to resend them again, which was probably a bad omen or something. But everyone was excited enough to be traveling that no one seemed to mind (and plus, in the Arab world, you don’t leave on time. You just don’t). I picked a seat in the back of the coach bus with Silas and some other friends, and ate an orange as the bus rolled out into the desert past Zarqa.

Dona made cookies for everyone to share

I quickly lost track of the conversation (Silas and I were the only non-Arabs in the back of the bus, and they were talking way too quickly and slangishly for us to figure out the jokes) and with the exception of the massive potholes that fill every non-airport road in Jordan, would have drifted off to sleep. Silas tried to listen in for the most part, as it was “good Arabic lessons,” which I always half-disagree on because I feel rude asking my friends to re-translate all their conversations afterward to see how close my mental approximations of their speech is. It was a short ride up to the border, made shorter when Yanal continuously erupted into loud, roaring Bedouin songs, which every other Arab on the bus clapped and sang along to on the bus, while the rest of us got the “translating internally” looks on their faces. You know the one I’m talking about; when you cock your head, furrow your brow and frown, and mouth words while shrugging at your other azjnubee friends.

We reached the Jordan/Syria border at quarter to one, at which point we had to shell out for our “Jordanian Departure Fees” – yes, that’s right, you have to pay Jordan money to leave the country, something which all the travel guides for the country tell us. Ironically enough, it costs JD8 for a Jordanian to leave his/her own country, while it costs the rest of us only JD5. This marks the first, and only time ever, that I have seen a Jordanian pay more for something than a foreigner. The wait wasn’t bad here at all – we just filled out a piece of paper, a soldier came onto the bus to look at our new red stamps that said we had paid our dinars, and the bus continued moving through the barricaded no-man’s-land section. The whole process probably took about half an hour for the whole bus.

How welcoming is a cement wall for your first view of Syria? Surprisingly enough, the Jordanian side is the greener side of the fence

Syria’s checkpoint area seemed to be a lot larger and well-manicured compared with their neighbor, probably because they knew that people were going to be spending many more hours enjoying those strips of land. We all filed into the checkpoint building which was large and warehouse-like, to begin the process. Here we were given a large blue form to fill out, with information including “Father and Mother’s names,” which I dutifully filled out in both English and Arabic, knowing that I could win a few brownie points that way if I spelled them properly. Half-jokingly, I suggested that we should sing “Zahret al-Madaen” for the officers, which was greeted with a chorus of “NO WAY.” Keegan, having traveled to Syria before, pointed out that they are very suspicious of foreigners who know Arabic, especially ones who might know it well enough to sing in it. I quietly slunk over to a corner of the room and played video games on my iPod with Janell while the surly, brown-coated Syrian military poked at our passports and forms as if they expected George W Bush to pop out of them with a bouquet of flowers.

The Jordanians quickly were passed through in only about 20 minutes, and they vanished out of the building to the duty free to stock up on Syrian duty-free liquor and beer, which is about a quarter of the price of the Jordanian stuff despite being identical. Got to love those government taxes here (300% on alcohol). The only Arabs left with us were Shireen, who kindly waited with us because she is super-cool, and Ala’, who is Iranian and therefore has to wait in line at probably every border at the planet because every guard seizes up at the sight of an Iranian passport (this is not the same Ala’ that I’ve spoken of before; we have two of them in the choir). In the end though, the Syrians finally realized that we weren’t spies/terrorists/pig farmers and let us through, in a little under 3 hours. Everyone “in the know” in the group agreed that this was by far a new record, especially for a group this large.

The foreigners quickly joined the others at the duty free to pick up cheap items. I was amazed by the prices on alcohol, compared with Jordan. A full liter of Goldschläger (one of my personal favorites for its hedonistic appeal of drinking pure gold flakes) was only USD18, which is probably a better price than you can get in most American liquor stores. Besides the obvious appeal of alcohol, many of the choir members quickly tore into massive bars of chocolate or, more ironically, massive crates of cigarettes. Ah, so many vices in one place – it’s a wonder that more ascetic extremists don’t target duty free shops before anything else.

Damascus was only another half an hour away, but we weren’t going there immediately. We briefly stopped first at our hotel, the Ebla Cham Palace, to drop off our bags and get some coffee from their piano bar, and then headed into the city itself for our first joint choir practice. Although we got lost a little bit on the wide, crowded streets of Damascus, we finally found the place and were greeted by the Syrian choir, an elegant-looking group of young people led by a boisterous Russian director named Victor Babenko. The Lebanese choir hadn’t yet arrived (perhaps as lost as we had been) so we started without them, singing our three “unison” pieces to learn each different director’s style. Shireen would be leading the first one, “Umen” which we hadn’t done in Jordan at all, but was quite easy, Victor the Spanish mass “Missa Criolla.” The Lebanese director would of course be directing “Zahret al-Madaen” as Fairuz, its writer and most famous singer, is from Lebanon. Dozan wa Awtar’s members immediately raised their eyebrows at some of the changes that Victor had made in “Missa Criolla,” including changing the “humming” vocalizations (which were clearly written as “Hum” in the music) into “Nnn” throat sounds. He also added in a new movement into the song which Dozan hadn’t yet practiced, which made me feel bad for Rob and Ala’, its soloists, who had probably learned the thing in about a week. As Rob revealed to me later, singing this movement, “Credo,” was done as theatrically as possible to distract the audience from the fact that he had no idea what the right words were. The Lebanese choir arrived right at the end of our practice, apologizing for their lateness, just in time for our Jordanian choir to sing a few from our repertoire for them.

We adjourned back to our hotel for the night with the Lebanese choir, who like us were put up there by the Syrian government (the same kind people who paid for our visas). My roommate Silas and I checked out the place, looked out the window into the beautiful Syrian mountains and completely unfilled and out-of-order pool (what a waste of my swim trunks), and then joined the rest of the choir at dinner in the lower level. The next few hours were filled with boisterous Arab songs sang between increasingly-swaying choir members of both the Lebanese and Jordanian variety, thanks to a massive bottle of Smirnoff provided from the Lebanese conductor Barkev Taslakian, which was passed between the group as they ate and sang. How massive, you ask?

This massive.

Good night, folks, indeed. Silas and I woke up at 8 the next morning (headache-free) with plans to visit the Old City of Damascus before our next joint choir practice at noon. The front desk summoned both Syrian Pounds (otherwise known as Lira, in a confusing twist of British imperialism and modern Arabic) for us and a taxi to take us into the city. The ride was 800 pounds, which seems like a lot until you realize that 67 pounds equal one Jordanian Dinar. The “taxi” was curiously unmarked, compared with the bright yellow taxis that buzzed around us, and although the driver was perfectly friendly and conversational, both Silas and I suspected that the employee at the front desk had merely called up one of his buddies to ferry some tourists into town. A good way to make 800 pounds on the side if you were already going in to go grocery shopping. We were dropped off at the gaping black maw of the Souq al-Hamidiyeh, a 230-year old covered market that stretches back over half a kilometer into the city. From a distance, I thought the huge front entrance was for a train station, or maybe a collapsed house, but when we got up to it I could see that it was merely a regular street or alleyway that some resourceful team had covered with a thin roof of tempered metal, which over the centuries has worn down so that the street below sparkles with tiny dots of sunlight while dust motes dance past your vision like sprites. Silas and I strove bravely in, hands on our wallets, and Silas was immediately pooped on by a pigeon.

“Son of a…” Silas began, grabbing the sleeve of his shirt and staring angrily into the black roof above us, which swarmed with pigeons. Seconds later, as if summoned by the sound of falling feces, a bespectacled young man appeared next to us, proffering a tissue and a big smile. As Silas wiped his sleeve off, the man led us off to the side of the market, explaining to us that he owned a souvenir shop and he’d be happy to show us around, which we politely declined, saying instead that we were on our way to look for a ATM. We found one (which was broken) but the helpful young man had vanished back into the swirling crowd of tourists and hijab‘d women. “That was surreal,” commented Silas. “Awfully convenient, too. Wait – do you think he trained that pigeon to poop on people so that he could rescue them and then sell them things?!?”

We spent the next 2 hours wandering about the bustling souq, gazing a fake leather handbags, slightly less-fake looking Damascene swords, and completely genuine wishes for us to “just step right way and look at this store, please!” At one point, an elderly man in a rumpled suit stepped out of a shadow, shook my hand vigorously and said “Hello Hello How are you, where are you from?” I responded slowly – “uh, Canada.” Silas replied with “Germany.” Without releasing my hand, the man grinned broadly. “I have sales for people from Germany and Canada, come right this way!” Silas instantly resumed his forward movement, and I was about to follow until I realized my smiling friend had not yet given me my hand back. I thanked him, and he protested with a smile, clinging to my arm. I probably dragged him a good 10 feet before I smiled apologetically, reached down with my other hand, and literally pried his hand off my wrist, then sprinted after Silas. We wandered in and out of the covered part of the market into the side streets, examining the old museums and architecture of the place and the occasional fountains. I noticed that there were considerably more bikes in Damascus than in Amman, which made sense considering how much flatter this city was than my own. Here in the north, trees were more prevalent as well, leading to the increased bird populations which Silas had already discovered. The architecture itself somehow seemed more European to me as well, which also makes sense because of the difference of age between the two cities. Damascus has existed as a bustling center of commerce for thousands of years, whereas Amman has only really existed as a city for 90. I’ve heard from people that Amman looks a little like a miniature, cleaner version of Cairo, and since all of the construction is done by Egyptians it’s not really a mystery as to why that is.

After the relative darkness inside of al-Hamidiyeh, the white walls of the Umayyad Mosque are particularly blinding (for both humans and cameras!)

My favorite part of the sight seeing was by far the famous Umayyad Mosque, one of the largest and best preserved ancient Mosques in the world, which is situated at the far end of the Hamidiyeh, right as the roof covering between the buildings finally runs out and is replaced by ancient stone columns a mere 100 meters from the huge gates of the mosque. Silas and I procured our 75 pound tickets from a small office to the side, where groups of foreign tourist women were required to pick up covering before entering the mosque. Islam requires that all women be covered, and although most countries have relaxed these laws in most circumstances, it is still shar’iah and sacred that no woman may go into a mosque without covering. When the gray, shapeless plastic cloaks were put over the women, they were transformed into gray, shapeless, sexless blobs that made whisking noises while they walked, like walking tents. Obviously, this was the entire intent of the Islamic law: the less sexual women are, the less likely they are of corrupting the men with their wiles.

Returning to the main gate of the mosque, I almost made the fatal mistake (okay; not really fatal but improper) of stepping over the high metal sill without removing my shoes. I was shoved out of the way and watched as a few Muslim men removed one shoe, stepped carefully over the half-meter barricade, and then turned back and removed the other shoe before stepping all the way in, then duplicated their movements, tucking my hiking boots up under my arm. I ironically remembered back 7 months ago when the Sheikh of Ghor Safi teased me for wearing these same boots in the Arab world, where removal of one’s shoes before entering a home or holy place is so common that wearing anything heavy and cumbersome is considered foolish. I always wear these shoes for hiking and traveling though, for their strength, but I wished I had my usual lace-less loafers intensely after half an hour of cradling a kilo of leather and rubber in my arms like a small ugly child.

The huge white courtyard of the Umayyad, plus Silas' finger. In the middle is an example of a gray-robed tourist.

All worries about my shoes vanished when I stepped into the foyer in my socks and looked up into the wide foyer of the mosque. Exquisitely done up with tiny green, silver, and golden tiles for 100 meters, I was literally left breathless with the care and detail of the artwork surrounding me. After the door we had just stepped through, we were confronted with a wide, white-tiled courtyard with a building to our right, and several smaller roofed shelters throughout its space. We first examined the mosque itself since its door was immediately to our right, and stepped into a huge, red-carpeted room, with high ceilings and ornately carved walls and pillars, bare except for an occasional electronic clock every few dozen meters counting off the time towards the next of the 5 daily prayers (which, like Ramadan and everything else, change daily depending on lunar cycles). The building was about as long as a football field, filled with people of both the touristic and praying Muslim variety, all lit with a pinkish glow from the red of the windows and the carpet.

Near the far end of the mosque, a bright glint of green caught the eye, where a particularly large mass of tourists was gathered. Silas, with his knowledge of Biblical history, told me that this was one of the numerous supposed sites of John the Baptist’s final resting place and tomb. “Not so fast!” I quipped, remembering my own lessons. “Which part of him is here – his body or his head?” Turns out it was his head, which was neatly removed from his body in 36AD and rumored to have been found buried here when the mosque was being constructed in the early 8th century. Technically, there is “some” chance of that, as a church to John the Baptist occupied the location in the centuries preceding the Islamic conquest of Damascus.

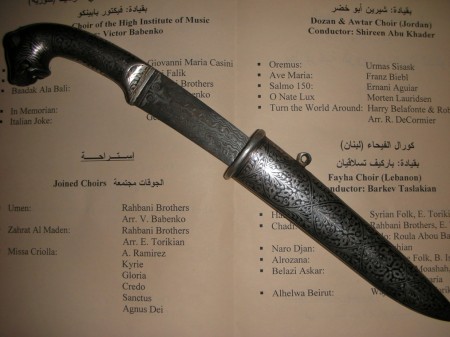

We wandered around outside for a few more minutes, enjoying the sunshine and beautifully restored artifacts on the grounds, the white tiles beneath our socks cool to the touch from the thousands of other travelers. However, we needed to keep moving in order to make it to practice on time, so we left soon afterward, unfortunately at the same time as an Arab tour group, who literally ran over Silas as he was trying to put on his shoes again in the exit doorway out of the courtyard. We continued on the narrow alleyways outside the mosque, asking directions occasionally and eventually finding the street “Bab al-Sharqi” which means Gate of the East. Although I found myself glancing more and more frequently at my watch with no sign of the Bab itself, Silas picked up a small dagger at a shop in the street, after haggling with the vendor for a good ten minutes and showing off his Arabic knowledge before guy relented on his original price and gave it to him for 500 pounds less than before.

Moments after leaving the shop, we ran into Shireen and Barkev and their respective choirs, marching from the huge stone archway that was the original Bab al-Sharqi in the ancient city. Our target church and site of the night’s concert was only around a corner, which Silas and I would have missed if we hadn’t met up with everyone at that moment – the Kaneeseh al-Zeitoon, or Church of the Olives, which was a strikingly medieval looking gray building with a large clock in one of its towers. Once inside, the three choirs were shuffled about as the directors tried to figure out the best way to fit almost 100 people into a transept the size of a bedroom. The answer: painfully. Nedy and I were wedged up into an alcove to the upper right, and poor Silas was stuck behind some sort of throne-like thing for 20 minutes until Barkev noticed him and moved him somewhere else. In the actual practices themselves, Victor’s interesting style of conducting left me and the other Jordanian basses in silent fits of barely repressible laughter. He was extremely vivacious to watch, punctuating his sweeping hand gestures with shouts of “HA!” and “ERRGHH!” and gritting his teeth maniacally when he told us all to change the “hum” into a “nnnn.” At one point, Louai commented that he must have a second job as a horse jockey, and this mental image was funny all by itself when moments later Victor snorted, whinnied vigorously and flared his nostrils as he waved his arms about. For the next 3 minutes I was overcome with laughter so intense that I had to duck behind the curtain into the alter and giggle helplessly as Nedy and Louai grinned and made snorting noises under their breaths. For the rest of the practice, I was unable to look directly at the man without chortling like a madman, and left the stage feeling somewhat lightheaded.

The practice lasted about two and a half hours, and we had only a brief stop back at the hotel to check out and change into our black concert attire before being swept back into Damascus for dinner at a classy restaurant and argeilleh bar across the street from the church. I couldn’t believe that some of my fellow choristers were smoking with the concert 45 minutes away, but I guess if your respiratory system is used to it 20 minutes of smoking isn’t going to do any more damage than it’s already done. After dinner (sans argeilleh in my case), I wandered back into the Bab al-Sharqi street and acquired a little dagger of my own, like Silas’ except instead of being smooth silver, this one was etched into a “Damascene-esque” version of the ancient method of creating swords in this part of the world. For JD30, I was more than happy with my purchase – even if I didn’t try to heckle the vendor down in price like Silas had.

The concert started surprisingly promptly at only a little after 8PM, first with our show, then the Lebanese, and finally our Syrian hosts. The lovely church was a perfect venue for our choral Latin chants and masses, although the large gray-blocked columns, each 2 meters thick, made for difficult photography of the other choirs as we sat. We all sounded great, although the other choirs were singing only Arabic or Latin without any English which meant I couldn’t understand anything. That fit with the makeup of our choirs – Dozan wa Awtar is at least 30-35% foreigner, whereas the other two were entirely Arab. Personally, I was a little disappointed that the concert was not better attended, especially with three groups performing – early on, the entire back remained unfilled and it wasn’t until we reached the joint concert section that we were at almost capacity. Since a few hours had passed since Victor’s snorting outburst and my reaction to it, I had no trouble “keeping my game face on,” so to speak. Just as with our concert in Jordan a few weeks ago, the entire building rose to thunderous applause, cheering, and even a few tears of joy when our 90-strong, thundering voices hit the final notes of “Zahret al-Madaen.”

As it was already 10 at night by the time the concert finished, we didn’t stick around long after the show – enough time for people to change out of their suits in the church’s office building, and we left directly from the bus, who picked us up just beyond the Bab. We stopped for schwarma at a stand at the edge of the city, since many of us had never had the famous Syrian variety before. Our plump chef smeared the chicken in a pool of spices, fat, and oil before grilling it, giving it a strong pungent flavor, especially when he added the traditional pickles that are always added to chicken schwarma. It was quite tasty, especially for only 40 pounds, but of course Reem will continue to be my favorite!

The bus ride home was mostly silent, and there were no problems at the border – the guards on either side let us through without issue at half past midnight. The Syrian official squinted darkly at us through the glass wall, shouted something to his supervisor who was sleeping at a desk in the corner, who jerked angrily, cursed at the underling, and then went back to sleep. Ah, the efficiency of the military machine.

On Monday, we’ll be having an awards night as kind of a “closer” for this half of the season. There’s going to be a summer season, and a performance for the Pope (which only a few of our members are performing for, but many are attending), but first, Shireen wants us to relax and unwind and kind of have a mid-season Icebreaker to tell stories about each other. I’m glad she waited til halfway through for this, as now I have plenty of stories about my fellow choristers – as I’m sure they do about me as well! Let’s hope they keep my dignity in place…

No one has asked me for any stories yet. *pout*

i am manufatcurer of damascus daggers swords