I can’t believe it’s already been almost two weeks since I arrived in Central Asia, and I haven’t had the time to even post one good-sized blog entry about the trip. I’ll remedy that with a couple now, but in order to prevent confusion on the dates of my experiences, I’ll be backdating entries to their original occurrence date. I’ll post the rest, and update these entries with photographs, when I get back to Jordan. For now though, let’s start with my day in Istanbul, Turkey.

The plane ride went smoothly and was very short, navigating neatly around Palestine to avoid having to deal with Israel and “their” airspace. I was surrounded by Italian tourists in the small plane; most likely the religious faithful on their way back to Rome after following Pope Benedict to Jordan the previous weekend. Because of the time of day, I spent most of the time napping, and awoke with a jolt as the plane started its steep decent over southern Turkey. My knowledge of Turkish geography was very limited, and continues to be so – until looking it up the night before, I had thought that Istanbul was the city in the middle of Turkey, which I now know is actually the capitol, Ankara.

In the airport, I was dismayed to discover that my Jordanian dinars were entirely useless. My limited vocabulary of Turkish phrases consisted of me pointing helplessly at the JD50 note in my hand and pointing towards the sign that said “exchange” in multiple languages. I tried 5 different exchange offices in the airport, at which every official took one look at the unfamiliar currency and shook their heads silently. I was just about to head towards the bright exit sign, with the most familiar Turkish word, Çıkış, or “Chukush” as we would pronounce it. Suddenly, I was poked from behind by a guy in a uniform, who grandly asked me in passable English where I was planning on going. It seemed like he worked for the airport, so I told him helplessly that I just wanted to find a way from the airport to Hagia Sofia and the Sultanahmet “Blue Mosque.” He officiously steered me through the luggage-bearing crowd to a rental car window and suddenly I realized his game. The rental car man also spoke English, of course, and told me that it would be 100 Turkish Lira, or about 63 USD, to take me to the sites included picking up me at…(here he inspected my plane ticket) 6:30 PM so that I could catch my flight to Dushanbe at 8:30. I balked at this, but he was more than insistent; he was downright pushy. He rang up the fee without even asking for my confirmation and extended his hand for my credit card. I weighed my options: I had no guidebook and no idea about what was normal in this country, but everyone knows that tourist locations love to gouge people, especially ones “fresh off the boat” such as myself. What choice did I have that wouldn’t take an hour of me hunting around looking for a better option? I paid the money and was escorted to the parking lot to meet my driver, Murod.

Murod was a shifty fellow who laughed a little too much and spoke only a half dozen words in English, three of which were “tip” and “give me?” I raised my eyebrow and communicated with him well enough to tell him that I didn’t have any smaller lira denominations now; I had just arrived. He laughed for several minutes at this, told me “later” and “6:30” and I was dumped from the car in the parking lot between the Hagia Sofia museum and the extraordinary Sultanahmet Mosque. Backpack in hand, I started for the latter, joining the throng of camera-toting tourists maneuvering through the gardens towards its massive wooden gates.

An amazing combination of Asia, Europe, and somehow, Disney World (that last one is just a gut feeling)

The mosque is one of those locations that neither words nor pictures can describe; you just have to see it for yourself. The outside of the building looks like they took a regular domed mosque with a few minarets and stretched the entire place into a cavernous interpretation of the Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany. The line was long but moved quickly, and as far as I could tell there was no fee or gate guard – people just walked in line, saw the huge interior chamber, and left. As I expected, we were stopped outside the door and asked to remove our shoes, and even provided little plastic bags for us to put them into. Of course, they weren’t designed for size 13 hiking boots and even with one boot in each bag, the weight tore the straps off within minutes and I was left to pathetically stuff my baggies under each armpit, where they hung like bizarre waterwings.

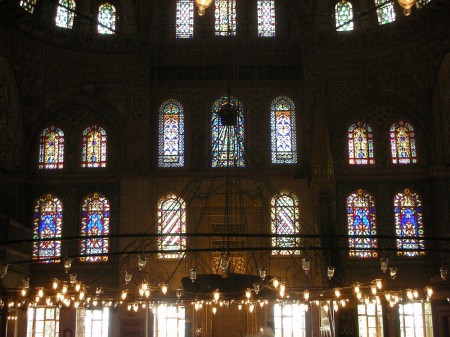

Glowing fairy-globes and intricately-cut stained glass windows crown the masterpiece that is the Sultanahmet

The first thing thing you see after crossing the threshold are the walls on the opposite side of the chamber, which pull your gaze upwards to see the ceiling – and what a ceiling it is! Countless thousands of intricate mosaics and patterns of leaves, flowers, and Arabic lettering cover the interior of the domes and minarets above you. The sheer amount of effort that it took to paint that room, which looks about a cubic kilometer in size, must have been staggering. Like the Kaneeseh al-Zeitoon in Damascus, the mosque is supported by four huge stone pillars, two of which are accessible to us tourists, and the other two on the far side of the room overlooking the Mediterranean Sea are separated by a gate to divide the faithful and the khafereen (infidels). The infidels far outnumbered today’s faithful, though – I could only see maybe a dozen Muslims kneeling near the glass, compared with at least 200 of us on the other side. A hundred small porthole-like windows ring the main dome, providing the majority of the limited light in the room, as well as a large and particularly ancient-looking series of low-hanging chandeliers suspended just above our heads, which seemed to be made of cast iron and were filled with incandescent bulbs that looked like they were probably about as old as the mosque was. And the place was almost entirely silent. Besides the swishing of our socked feet and the hushed murmurs in a half-dozen languages of tour guides leading their charges about, any uttered sound was quickly swallowed up by the thick red carpet that covered the floor.

Using my amazing solo camera skills that I picked up in Britain two years ago, I was in the process of attempting to balance my camera against my shoe on an alcove to take a picture of myself and the ceiling in the mosque when two young Asian women took pity on me and asked me if I needed any help with my act of vanity, and whether I could take their picture for them as well. The three of us spent the next few minutes figuring out light settings for the room and how to use the exposure and autofocus properly – it helped that one of them had almost the exact same model of camera as me, too. They introduced themselves as Satomi and Ayumi, Japanese flight attendants who had just came into Turkey the previous night on a flight that had some extra seats. They were surprised to learn that I was working in Jordan, and Ayumi exclaimed that she had just been there with her airline, Dubai Air, last month. The three of us agreed that it would be better to sightsee together, and of course our obvious next destination was the Hagia Sofia, which was only a few minutes walking distance away from us.

The Hagia Sofia, while not nearly as impressive on the outside as the Sultanahmet, is nevertheless just as lovely on the inside, if not more so. The three of us acquired a guide, Barish, at the gate, who repeatedly insisted that he was licensed. My Japanese companions only had euros with them, and Barish reminded them that the ticket gate would only take lira, but that he would buy their tickets for them if he was hired, a fact that played a definite role in our taking him on. After passing through the requisite metal detectors, we found ourselves on a sunny sidewalk outside of the gray stone building of the museum. Bashir explained that this site was the home of the first true Christian church in the world, built by Saint Paul in the decades following Christ’s ascension, but that original wooden church had been burnt to the ground after only a short time. Over the centuries, the church was rebuilt in stone several times, and after the Muslim conquest it was converted into a mosque, the minarets were added, and it existed this way for centuries until the past few decades, when it was more recently turned into a museum and tourist attraction.

Barish led us into the multi-layered building, which was laid out in rings which worshippers could enter only depending on their class and power. The outer ring was simple, with a couple baptismal fonts in it, the second ring was more ornate with marble insets on the walls as well as paintings of Christ and Mary that were in remarkably good shape. We asked Bashir how the paintings and mosaics of the Christian figures had survived so well, and he explained that when the Muslims took over, they had chose to cover all of the figures and faces with plaster and clay. The clay had chemicals in it which unintentionally preserved the colors and tiles under it, and when it was removed centuries later, it was in as perfect condition as when it was originally covered. Islam is an “iconoclastic” religion, which means that pictures of saints and God, and sometimes even of people at all, are forbidden – you may remember this several years ago from the “Danish Cartoon Controversy” in which a newspaper in Denmark printed a political cartoon depicting the Prophet Mohammad with a bomb as part of his turban – this rubbed Muslims the wrong way for both the picture of the Prophet, and for the obvious implications of terrorism being “built in” to the religion.

The final doorway is known as the “Emperor’s Gate” as only the Emperor would be allowed to enter the large inner chamber of worship. The inside of the room was dominated by a large scaffold in the center, completing restoration on some of the paintings on the ceiling, but that didn’t detract from the beauty of the rest of the room, which was covered in Arabic scripts for “Mohammad” “Allah” and “Ali” – important names in Islamic theology. High in each corner of the room, massive paintings of six-winged seraphim angels guarded each pillar that supported the building. “Do you see the large jewels painted in their centers?” Bashir asked us. “When the angels were originally painted, it used to have their faces there, but the Muslims painted jewels over them.” This gave the once-mighty angels the unfortunate comic effect of looking like diamonds with fluffy wings attached to them. Bashir also commented on the large dome above us, asking us if we had seen the Sultanahmet Mosque yet. “Well, when Islam was started, they did not know how they wanted to build their places of worship at that time. It was this very church, and this dome, that all Mosques were based on from that point forward.”

The four of us wandered for about half an hour, Bashir pointing out carvings and frescos and telling us approximate dates of their creation, as well as where the building materials had come from – some pillars from Syria, some wall panels from Greece. In the front transept of the church, where the priest, and later the prayer leader of the mosque would have stood, Bashir pointed out the flaw in making this Christian church into a mosque; the pulpit in most Christian churches are arranged to the east, but here in Turkey, Mecca is to the south, which required some reorganization in order to make everything proper. We saw what he meant; there was a wooden platform in the transept and to the right of it, and all of the worshippers would have been angled slightly to the right compared with in Christian times, when they would have faced straight ahead.

After the tour, we paid Bashir in our combination of euros and lira, and he instantly melted into the crowd to look for more tourists. Satomi and Ayumi needed to return to their hotel to check if their airlines needed them to fly somewhere else, so I bid them farewell and retreated to a small café near the Hagia Sofia to plan where I wanted to go next. I ordered some lamb kebabs for 11 lira, and it was about then that I realized my blue pen had exploded in my breast pocket and I was leaking ink all over my shirt, chest, and passport holder. Thankfully, the Turkish word for “toilet” is just “tuvalet” so I was able to get changed into a spare shirt, which I luckily had with me in my carry-on luggage.

I still had several hours to kill before my pickup at 6:30, so I decided to search for the Kaplicharshi market, which according to a map that I picked up, was somewhere nearby to the west. I walked uncertainly in that direction, trying to avoid being flattened by the high-speed electric trolleys that whirred through the center of the street at odd intervals, when I heard voices behind me – that I could understand! It was a group of young women, also bearing maps, and talking about the same market I was searching for. They saw my map, asked me where I was going, and we discovered were going in the same direction. It turned out they were part of the women’s soccer team from a university in Toronto, Canada, who were playing an international tournament that night. Like me, they had little idea which direction they were heading, but oddly enough five young blonde women had little difficulty receiving directions and offers of guidance from the young, English-speaking Turkish men lounging in the street. I decided it was in my best interest to stick with them for the time being.

Upon reaching the market, which surprisingly was hidden behind the Nuruosmaniye Mosque, I left the women behind looking at some carpets and purses and continued into the Kaplicharshi’s vast and winding depths. Like the Hamidiyeh in Damascus, Kaplicharshi is a covered mosque, which has been even better preserved and is much more suited for money-carrying tourists. Signs in German, English, and Turkish adorn the ceiling with facts about the market’s construction and historical significance, and I was almost run over by slow-moving carts several times in order to read them properly. The ceiling was an attractive off-white color, clean, and had decorative paintings and symbols around its edges, as well as round window-ports every meter to let in the bright afternoon sunlight.

Jordan and America need more classic, ancient roofed markets like this. The sooner we build them, the sooner they'll be ancient...yalla!

These vendors were of a different breed than in Amman, and even in Damascus – I found myself grabbed several times and led to a shop several times for “tea” and young men trying to sell me French jeans kept following me and telling me I needed tighter pants, which was slightly disconcerting. To head them off, I spoke in Arabic to most of them, or kept a few of my 1-dinar notes in hand in an attempt to make them think I wasn’t a money-laden Western tourist, just an oddly-pale looking Arab. Finally, this became tiresome, and I just put on my dark shades and headphones, which was 100% effective in discouraging vendors from engaging me unless I wanted to be engaged, and I could continue my window shopping unmolested.

The market covers several square kilometers, all of which is covered, and the signs above me boasted that at one time, it held as many as nine Masjid (small mosques) and even several small hotels under its roof. The mosque is still arranged into “neighborhoods” with specific functions, like leather products, food products, steel/metal products, and money-changing and banking. For a single lira, I purchased something like a hot pocket, a piece of flat hot bread stuffed with minced meat, and munched on it as I perused shelves of Turkish delight and something evil and black-looking on several shelves, advertised as “Turkish Viagra” for both “men and women.” Finally, I tarried longer than a few seconds at a shop selling chessboards, tea sets, and argeilleh, and the owners came out to greet me and I was pulled into the shop.

So began the most intense wheedling and haggling session I’ve ever been a part of. The first man opened by attempting to woo me into purchasing a half-meter tall argeilleh, although I told him right from the beginning that I was from Jordan where I could get any argeilleh I liked for a quarter of the price. “But this is made in Turkey, not like Jordanian argeilleh!” he insisted to me, and when I pressed him to explain the difference in form and function between different countries’ smoking paraphernalia, he instantly said, “Well, wouldn’t your mother like this tea set instead? Your wife, girlfriend perhaps? One hundred and sixty lira usually, but for you, I give it for 120!” Very nice, I told him, but can’t you see that all I have is a backpack and I can’t fit that large box with me? He then proceeded to take my backpack off me, opened it up, and attempted to stuff the box into my bag. “Done!” he proclaimed proudly, presenting his handiwork and my stretched luggage to me. At my raised eyebrow, he then dropped the price down to 100, then 80, then all the way to 45. “You’re killing me here,” he lamented, throwing his hands in the air. “What do you want from me? This is Turkish tea set! You can’t get this quality anywhere else!” In actuality I was a little put off by his continued claims of quality (which included stomping on one of the cups, which come to think of it, was really impressive) when he dropped the price to 75% of the supposed “original” price. “This will be like taking food out of your family’s mouth; I can’t do that my friend,” I told him. His colleague, who was balding and a little plump, stepped from the alleyway outside the shop at this, shouted at his partner for a few minutes in Turkish, and then apologized to me on his behalf. “My little brother doesn’t know how to sell things properly, my fine Jordanian friend.” He then proceeded to lead me through the rest of his entire inventory, a highly amusing and theatrical process taking about half an hour which involved him clutching his chest several times and saying, “You are a difficult man to please! But now my honor is at stake – I must find something to sell you if it kills me!” Although throughout the course of our bargaining I picked up my bag and made ready to leave several times, he always was able to produce something new from the back of the store and bring it forward with a winning smile. We finally agreed on a small camel-bone perfume holder with a hand painted picture of the Sultanahmet Mosque on it, and now, feeling confident of my ability to get them to drop the price on anything they could lay their hands on, got it for 20% of their original asking price. I tucked it into a side pocket of my poor, worn backpack and our business was finally concluded. I left the Kaplicharshi feeling like I needed a strong drink.

With my remaining hours, I headed south along new roads, following the sound of the sea and the ships making port, finally emerging suddenly from an alleyway and finding the waves breaking across the street in front of me. I walked along the promenade, watching the vendors with their balloon popping games proffer pellet guns to passerby, inviting them to try to shoot out balloons, bottles, and cans placed on the rocks below the concrete path. Fishermen with long, whip-like fishing rods that must have been four meters long cast off the promenade into the water below and men in turbans sold kebabs on thin wooden sticks. I balanced myself on a rock off of the walkway and freed my tired feet from their hiking boots, sinking them gratefully into the icy water and watching the waves slowly rise higher to soak my jeans as the tide gradually turned. In the distance to my left, I could see massive cruiseliners leaving from the channel between the Europe and Asian sides of Istanbul, vanishing into tiny dots on the smooth horizon.

Finally, with an hour before my scheduled pickup, I decided to head back to the rendezvous point, picking my way through the heavy traffic around the tourist-heavy peninsula and trying to remember the path that Murod had taken that morning. I took a few last pictures of the Sultanahmet at sunset with the sun reflecting off its turrets, and politely declined a shoe-shiner who continuously harassed me to allow me to polish my hiking shoes, even going as far as to sit down in my path and attempt to take off my shoes as I was walking, to my annoyance. I found Murod leaning against his car in the shade, smiling happily at me with arms crossed. He politely bantered with me to the best of his ability as he drove me back to the airport, and finished with a hopeful “Now, give me tip?” as we pulled up to the airport gate. I rolled my eyes and gave him five dollars, the equivalent of about 8 lira, mindful of the fact that I had already paid 63 dollars for this service. I was ready to continue onto Tajikistan and put Turkey, with its beautiful monuments and insistent vendors, behind me.

No one has commented on this post - please leave me one, I love getting feedback!

Follow this post's comments, or leave a Trackback from your site